Even in his own day, President Theodore Roosevelt was a cultural icon. Buffalo Bill included a segment about Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in his Wild West show. He rendered the 25th president the bastion of masculine bravado. Toymaker Morris Michtom focused on another aspect of Roosevelt’s character — in 1902, Michtom heard how Roosevelt spared a bear’s life on a hunting trip. He was so moved he created the beloved teddy bear.

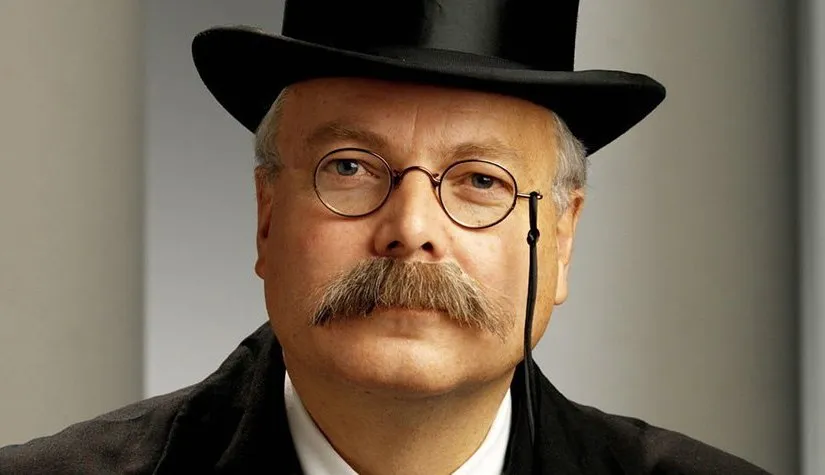

Actor Clay Jenkinson adeptly captures both sides of Roosevelt. At an event hosted by the Bill Lane Center and continuing studies scholars John and Catherine Debs, Jenkinson impersonated Roosevelt. Sporting Roosevelt’s distinctive spectacles, bushy mustache and cowboy hat, Jenkinson adroitly discusses Roosevelt’s passion for the outdoors, his opinion of Mark Twain, his run for the presidency in 1912 and his adventures in South America. While Jenkinson’s knowledge and interpretation of Roosevelt are certainly impressive, the most compelling part of his performance was his emphasis on Roosevelt’s continued relevance.

Roosevelt’s achievements are legion — he was an ally of the Progressives, creating the Food and Drug Administration and working to end child labor. He broke up large trusts, regulated the railroad and fought for campaign reform. He sought to conserve the environment and placed 230,000,000 acres of land under government protection; to expand American influence in the world, he built the Panama Canal. Roosevelt’s patriotism, however, contributed to several of his shortcomings. He was an ardent imperialist who supported the annexation of the Philippines. While he loved the Western landscape, he was often insensitive to the fact that Native Americans were often the original possessors of the land; he argued that they should abandon their ancient cultures and try to assimilate into white society.

Jenkinson does not try to obscure Roosevelt’s flaws. When he speaks of the feud between Roosevelt and Mark Twain, Jenkinson presents Roosevelt’s colonialist worldview. Throughout the performance, Jenkinson does not simply list Roosevelt’s accomplishments. Instead, he elucidates why Roosevelt acted in his idiosyncratic way. Ultimately, it is left for the audience to decide whether Roosevelt’s reasoning was sound. Jenkinson makes clear that prejudice was not the primary motivation for Roosevelt’s imperial policy. Instead, he genuinely believed that the United States would be emasculated if it did not build up an empire. In order to compete with domineering Europeans, Americans had to spread their ideals of liberty and democracy across the globe.

Jenkinson also examines how this patriotic fervor inspired some laudatory decisions. Roosevelt established the National Parks not just because he enjoyed the outdoors, but because he believed that these spaces played a vital role in defining American identity. Just as other countries preserved their history, America had to conserve these landscapes. Furthermore, Americans could only prosper if the capitalist system provided equal opportunity for all and wealth was not concentrated in the hands of the few. He longed to ensure that every American could partake in “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Jenkinson is not only a historical performer, but also a scholar. Along with some other North Dakota historians, he is currently working to establish the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library. (Roosevelt once said he “could not have been president had it not been for [his] experience in North Dakota.”) Jenkinson uses his thorough knowledge of Roosevelt to enhance the theatricality of his presentation. For example, Jenkinson tells how Congress finally reached a consensus on a budget bill in 1907. Senator Charles W. Fulton, an avid opponent of the National Park System, attached an amendment to the bill to limit the amount of land the government could protect. Roosevelt bristled at the amendment, but he was under immense political pressure to sign the bill. After some thought, Roosevelt devised a solution to this conundrum. He would refuse to sign the bill, but he would not send it back to Congress it either. After ten days, the bill would go into effect despite Roosevelt’s “silent veto.” Still, in those ten days, Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot placed sixteen million acres of forest under government control. Jenkinson makes the story more entertaining — he pauses as Roosevelt agonizes over what to do, and he smirks when Roosevelt confides in Pinchot. Finally, he breaks out into a grin and delivers the last part of his story with relish. Roosevelt made sure that most of the acres he protected were in Oregon, Fulton’s home state.

As humorous as the anecdote is, Roosevelt’s actions in this moment were consequential. Many of the forests around Crater Lake exist today because Roosevelt thwarted Fulton’s plan. Although Jenkinson speaks in Roosevelt’s clipped, antique accent, he also emphasizes Roosevelt’s relevance. Although Roosevelt’s favorite expression “bully” has passed out of use, the Food and Drug Administration still makes headlines. Jenkinson was transported to the event in an archaic horse and buggy, but the United States still transports goods through the Panama Canal.

Towards the end of the performance, Jenkinson took some questions from the audience. A few attendees were wondering what Roosevelt would have thought about President Trump. Jenkinson’s response was respectful, yet pointed. He noted that Roosevelt read a book a day, but Trump does not seem to possess that same curiosity about the world. It was a fascinating moment — Jenkinson was still in character as Roosevelt, so audience members were literally querying the past to divine the present. Still, Jenkinson’s performance suggests that the past is accessible even without the aid of an interpreter. Roosevelt’s legacy is manifested in the Panama Canal and the National Parks he protected. At these places, the sentiment that William Faulkner once expressed becomes palpable — that sense that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Contact Amir Abou-Jaoude at amir2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.