Though this year has seen controversy over free speech at Stanford, the dramatic history of free speech issues on campus, which spans over a century, consists of incidents that mirror recent events. Some historical events may even overshadow modern ones in terms of the harm they inflicted and the bitterness they generated in the Stanford community. The Daily combed through Stanford’s archives and spoke to community members ranging from campus media heads to alumni activists-turned-politicians to understand campus dialogue, past and present. This is the story of free speech at Stanford.

Jane Stanford objects to nativism

The start of Stanford’s free speech debate can be marked by an early controversy in the spring of 1900, when the head of Stanford’s economics department, Edward A. Ross, made a controversial speech off-campus.

“[Ross] argued that the high standard of living in America will be imperiled if Orientals are allowed in this country before they have raised their standard of living,” according to a Daily article from that year. “And that … California might easily experience the same famines as India and China if it had the same kind of men.”

Upon hearing of the remarks, Jane Stanford refused Ross’s reappointment. However, Ross, who was a favorite with students and with Stanford’s President, David Starr Jordan, was not easily silenced. Jordan, a eugenicist known to oppose “racial mixing,” convinced Jane Stanford to reappoint Ross on the condition that he would ultimately resign; Jordan hoped this technique would buy him time to convince her to let Ross stay on. Six months later, feeling silenced, Ross finally quit.

“[Stanford] is no place for me,” Ross said. “I cannot with self-respect decline to speak on topics to which I have given years of investigation. It is my duty as an economist to impart, on occasion, to sober people, and in a scientific spirit, my conclusions on subjects with which I am expert.”

Echoing today’s criticisms of “elites” who stifle speech, Ross said he was being targeted by high-status Californians.

“I have long been aware that my every appearance in public drew upon me the hostile attention of certain powerful persons and interests in San Francisco, and they redoubled their efforts to be rid of me,” he said.

In the year following Ross’s resignation, Stanford buzzed with talk about what constituted a violation of free speech. John Branner, who would become Stanford’s next President, expressed his support for free speech, but warned of the dangers it could bring. He described how professors should not display partisanship, disturb students or make statements that the university’s president could not stand behind.

“Some men give up life positions for the sake of their ideals and ideas,” Branner said. “This should be the course pursued by college professors who find their duties uncongenial.”

Many agreed that Jane Stanford’s pressure on Ross was not a violation of his speech. Others, however, were disturbed. In particular, history professor George Howard conveyed disapproval over Ross’ dismissal and was chastised by the administration. The Daily described the resulting backlash against Howard:

“[Howard] was asked to retract [his comments] or resign, and answered: ‘I resign.’”

Several more professors then resigned in protest of the University’s treatment of Howard. A few students also expressed their support in a petition.

“We sincerely deplore the forces which have resulted in your resignation,” wrote the students. “And we further take this opportunity of expressing to you our admiration for the dignified attitude which you, and those of the faculty who have resigned with you, have maintained throughout the present crisis.”

Leftists champion speech

After its fiery beginnings, the free speech debate cooled over the next several decades. There were many discussions about the principle of free speech, but fewer major incidents. Over time, the champions of free speech became leftists, including representatives of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and students who supported socialism.

In 1927, for instance, local ACLU chairman Harry Ward came to campus. In the same talk in which he argued that the ACLU did not have communist sentiments, he criticized universities like Stanford for smothering speech.

“Until there is love of free speech among university faculties and people in authority, we shall have repression,” Ward said.

Leftist students were also eager to speak. In the 1930s, many students joined the Walrus Club, a liberal group named after the creature from Lewis Carroll’s poem, “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” In that poem, the walrus says, “The time has come to talk of many things.” Fittingly, the Walrus Club met frequently in Old Union or at the Women’s Center to discuss politics, economics and society.

“There will be speakers on current affairs at the meetings, and sometimes two speakers who will present opposite sides of a question,” declared the announcement of one Walrus Club meeting.

Students brought controversial leaders like communist suffragist Anita Whitney and socialist politician Harry Laidler to campus. They discussed topics from labor rights to national elections to free speech itself. Throughout the ’30s, the club worked to air various viewpoints by holding frequent open meetings, which often included time for rebuttal and saw crowds of students spilling into the aisles.

However, the Walrus Club did not escape backlash. In 1935, a Daily article portrayed one discussion as an expose, describing a roomful of students gleefully listening as one speaker verbally dismantled California’s new Republican Governor. A letter to the editor criticized the paper’s coverage.

“The policy followed by The Daily in the reporting of campus events recently, however, is inconsistent with this attempt to defend our right to discuss controversial issues,” the letter read. “Next Thursday’s Walrus Club discussion on the San Francisco Strike will give The Daily an opportunity to show the campus that it is really in favor of free speech to the extent of resisting the temptation to print something sensational.”

The complaint came after The Daily published an editorial suggesting that major newspapers did not support free speech on college campuses. Afterwards, the paper continued publicizing the Walrus Club, printing dozens of pre-meeting announcements and short meeting summaries, until 1938, just before World War II.

Stanford’s “Free Speech” Movement

By the 1960s, fueled by the free speech movement across the bay at Berkeley, major concerns about the Stanford administration suppressing speech began to emerge.

“When I first arrived in 1966, the administration was trying to limit the activities of recognized student organizations,” said Lenny Siegel, former leader of Stanford’s Students for a Democratic Society and current Mountain View Mayor.

As far as Siegel remembers, the administration attempted to dictate which groups could have permits to hold rallies, as well as which could have a desk in the ASSU space. Generally speaking, however, publicly challenging such attempts was enough to thwart them.

Campus speech often manifested itself in the form of protest. In 1969 as part of the April Third Movement, named for the day of its organization, students staged a sit in for more than a week at the Applied Electronics Laboratory. The students were protesting the Stanford Research Institute, a group which worked on classified studies about technology like biological weapons. Ultimately, they ended much of the war-related research.

Students also distributed leaflets, held marches and staged sit-ins in President Wallace Sterling’s office, Old Union and the administrative offices in Encina Hall. The Administration expressed disapproval of such activities.

“It was a very acrimonious time,” said Philip Taubman ’70, then a student journalist and now a communications professor and secretary of the Board of Trustees. “There were a lot of hard feelings.”

According to Taubman, this was especially true for Stanford Presidents, of which there were three between 1968 and 1972. Richard Lyman, for example, who was met by chants of “Give ‘Em the Axe — Right in the Neck!” at his first convocation as president, wrote a book in his retirement which bitterly criticized the radical activists’ techniques, particularly toward the end of his tenure at Stanford. Another President, Kenneth Pitzer, quit after only a year-and-half due to the turmoil. The first of the three, Wallace Sterling, urged students to think more deeply about speech.

“In reaching for extension of personal freedoms — whether these have to do with speech or law or love — it may be that [students] have not come to appreciate that liberty to be possessed must be limited,” said Sterling.

Although he was concerned about students having too much of a voice, Sterling was also concerned about visiting speakers having too little. This concern was inflamed in 1967, when US Vice President Hubert Humphrey spoke in Memorial Auditorium. More than two hundred students staged a walk out, quietly exiting Humphrey’s talk in protest.

After the event, however, Humphrey was surrounded by a crowd of students shouting “Shame!” Guards with clubs kept the protesters away from his car as he left campus. Later, Sterling wrote a letter to the campus community.

“I am writing to you out of a deep concern for the preservation of free and civilized debate on the Stanford campus,” he wrote. “The ease with which a crowd, in the sway of strong emotion, can become transformed into an ugly and dangerous mob … has apparently been overlooked by a disturbingly large number of people.”

He went on to ask readers to consider whether the University could ethically invite certain speakers if their safety could not be ensured.

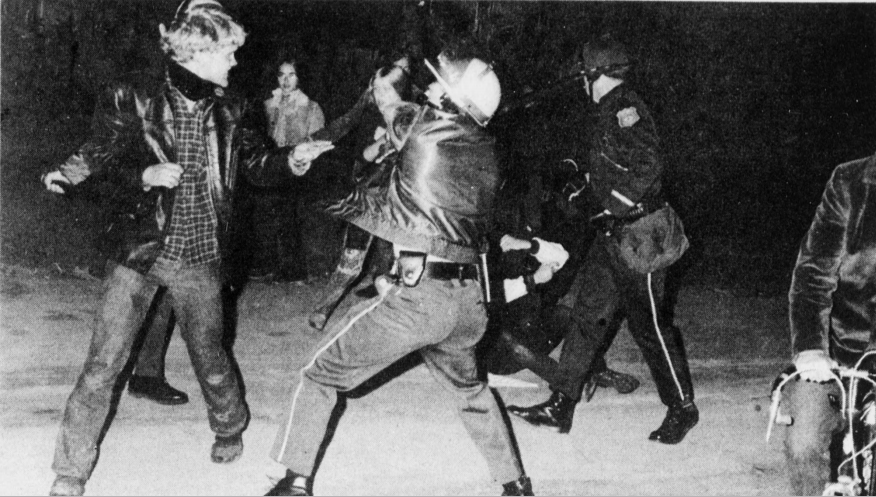

Indeed, free speech at Stanford in the Vietnam-era was sometimes marked by violence. In 1966, an English teaching assistant was beaten up while distributing leaflets against napalm. In 1972, when a crowd of seven hundred anti-war activists led by Siegel marched down Palm Drive carrying torches, police officers charged the crowd. Several students were admitted to the hospital for their resulting injuries.

Protesters also used force to convey their message, especially by damaging property. Before the aforementioned torchlight march, some threw large rocks to break the windows of the Hoover Institution.

“I recognized a fair number of people,” Taubman said, referencing the physically destructive protesters. “Certainly a portion of them were students. I can still hear the kind of unnerving sound of shattering glass echoing through the night…There was a lot of debate and anger over the destruction of property at Stanford.”

In February 1968, an anonymous act of arson damaged Stanford’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps building; the next month, another arsonist destroyed it. Bodily harm was not out of the question either.

“At one point some of the Leftist groups attacked other groups, both right-wingers and other Leftists,” said Mayor Siegel. “They weren’t targeting speech, but when you beat people up, you are stifling their speech.”

Is stopping speech, speech?

The explosion of speech issues on campus culminated with the dismissal of radical professor H. Bruce Franklin. In 1971, President Lyman brought a conduct charge against Franklin for disturbing a speech by Henry Cabot Lodge, former Ambassador to Vietnam, which was ultimately shut down due to disruption. Franklin was suspended pending his dismissal hearing. Witnesses disagreed about the extent to which Franklin heckled Lodge, with some saying he only made a few comments and others suggesting that he had incited students to riot.

“He was not fired for shouting down Henry Cabot Lodge, because he did not shout down Henry Cabot Lodge,” said Mayor Siegel. “There was pressure from alumni and the Trustees to get rid of Franklin because he was ‘leading students astray.’”

“We’re just not going to have this kind of witch hunt here,” Franklin said when questioned about his politics at the dismissal hearing the next fall.

Donald Kennedy, the Chairman of the Advisory Board at the time and another future University President, replied, “We’ll tell you exactly what you’re going to have.”

In a letter to Franklin, Lyman alluded to another incident that occurred two weeks after Lodge’s speech, when, after Franklin spoke at an anti-war gathering, protestors occupied the campus Computation Center reported to contribute to war programs. Franklin did not enter the building but encouraged the demonstrators from outside as police confronted them. Lyman charged that, among other transgressions, Franklin had “led Stanford students and others to … conduct themselves in an unlawful manner.”

Ultimately, Franklin became the first tenured faculty member to ever be fired from Stanford.

While many felt the University was limiting Franklin’s speech, others felt that leftists like Franklin were actually the ones opposed to free speech. The staff of The Arena, Stanford’s Libertarian newspaper at the time, wrote an article which quoted one activist, Janet Weiss, as saying, “We’re not interested in free speech, we’re interested in the people’s rights.”

The article also described a campus atmosphere that made conservatives and apolitical students unable to speak freely. Some faced verbal harassment and threats.

“Ask the staff members who have been prevented from working because of the dangers of mob violence: who are the oppressors?” the Arena staff wrote. “Ask the students of a freshman English section who were told by their [teaching assistant] that they needed to be ‘set straight’ and were consequently assigned the Quotations of Chairman Mao: Who are the real fascists?”

However, Siegel distinguished between taking on public figures and stifling the speech of ideological opponents who were not actors on the national stage. To him, free speech had more to do with who had power and a platform.

“The Lodge incident forced us to think through what speech needed to be protected,” said Siegel. “I was comfortable with the Lodge heckling because he could be heard, and he was heard nationally. The heckling was a way to protest the war — our speech. I would not have been comfortable with shouting down unknown proponents of the war.”

Hate speech banned and unbanned

When the Vietnam War ended, new concerns came to the forefront of the speech debate. In the early 1990s, tensions between unrestricted speech and protection from hate crimes flared. In the late 1980s, discriminatory incidents occurred across campus. A swastika was found painted on a wall in East Lagunita, white students caricatured Beethoven as a black man and hung their drawing on a black student’s door in Ujamaa and students protesting a resident’s eviction from Otero were criticized for a demonstration resembling a KKK rally.

In response to these events, the Student Conduct Legislative Council proposed an amendment to the Fundamental Standard known as The Grey Interpretation after the professor who drafted it. The Interpretation would restrict speech that victimized individuals or groups based on identity. It immediately garnered criticism.

In a KZSU debate, Computer Science Professor John McCarthy defended the right to absolute free speech and expressed concern about the University limiting it at all. At one point, he was asked whether Nazism or other hate groups had a right to speech on campus.

“It’s very important that if we’re going to have free speech, we have it for everyone,” he argued.

Nonetheless, the Grey Interpretation became part of the Fundamental Standard. It was never used as a rationale for disciplining anyone; on the whole, campus discourse remained civil, and there was no need to test just how far the principle of free speech went.

Still, in 1994, several students, including then-Editor-in-Chief of The Stanford Review, Aman Verjee, brought a lawsuit against Stanford in Corry v. Stanford University with regard to the amendment. They argued that the code violated California’s Leonard Law, which prevents private universities from abridging speech with rules that would be illegal for the government to enact. The students won and the provision was removed from the Fundamental Standard.

The recently-appointed University President Gerhard Casper said that he did not think the ruling would lead to much actual change, positive or negative. He did, however, express disappointment.

“I thought the First Amendment freedom of speech and freedom of association is about the pursuit of ideas,” Casper said. “Stanford, a private university, had the idea that its academic goals would be better served if students never used gutter epithets against fellow students.”

Free speech today

For seniors or anyone else on campus the last four years, these incidents and the debate surrounding them might feel familiar. Just as Walrus Club members once invited speakers to debate controversial viewpoints, this year’s Cardinal Conversations initiative brings together speakers with opposing ideas. Students once heckled Humphrey and walked out of his talk en masse; this winter, they did the same to Robert Spencer, whom many consider an Islamophobe. Just a few years ago, the Stanford Anscombe Society invited speakers some considered anti-LGBT, reigniting the debate of the ‘90s about what should constitute banned hate speech, and environmental activists staged a week-long sit in outside the University President’s office.

In many ways, students find today’s administration more friendly towards speech than the administrations of years past. Though Stanford barred the public from a Stanford College Republicans event in 2007 and tried to shut down an Obama rally held by the Stanford Democrats in 2008, the administration has generally been more hands-off in recent years or even started speaker series with the stated aim of promoting freer dialogue.

“I don’t think the problem is any longer about free speech, in that we are not currently seeing events being shut down,” said Stanford Sphere Editor-in-Chief Ravi Veriah Jacques ’20.

Sam Wolfe ’20, editor-in-chief of the Stanford Review, said that Stanford students respect free speech in a way some other college students do not — he appreciates that they mostly hold protests to express disapproval of speakers they do not like, but stop short of shouting those speakers down.

“Honestly I think it speaks to the political apathy of Stanford, rather than a spirit of free discourse,” Wolfe said. “I think most people don’t want to jeopardize their job at Google. They don’t want too say anything too radical, too controversial, and be branded with something other than ‘effective software engineer.’”

However, some students are testing the bounds of free speech at Stanford. The president of Stanford College Republicans (SCR), John Rice-Cameron, for example, has elicited particular attention this spring for bringing controversial speakers to campus, as he did by inviting leaders of the right-wing Turning Point USA to campus last week. Prior to the event, the Stanford Sphere reported that Rice-Cameron may have been trying to shape the event’s audience by deleting particular students’ tickets. For his part, Rice-Cameron expressed pride in increasing SCR’s visibility on campus and in supporting the airing of views many consider extreme. However, some feel like concerns around the free expression of such views is overstated.

“I feel like certain right-wing voices on this campus are quick to call out denial of free speech without thinking, without being actually introspective,”said Sphere writer Benjamin Maldonado, ’20. “And I think that’s deeply ironic given their so-called aversion to being victims.”

“On the left, you either have identity politics liberals or intersectional activists, both of whom are so convinced of their own moral and intellectual certitude that they don’t engage in discourse or debate,” Jacques added. “Meanwhile, the right on this campus — now seemingly best represented by John Rice-Cameron’s Trumpist SCR — shows no interest in well-meaning debate, but essentially just wants to ‘trigger the libs.’”

Wolfe also spoke to the sense that campus debate has room to grow. He mention conversations he has had with students who feel uncomfortable sharing their views in class.

“They feel there’s an implicit chilling effect, where they don’t really want to express an opinion that might be controversial because they’ll feel silently judged by their peers around them.”

To Wolfe, this phenomenon represents a hurdle to free speech.

“When people say things like, ‘Oh, you’re not legally barred from saying this, therefore there’s no barrier to free speech,’ that seems a very low bar to clear,” Wolfe said. “To live in a society where certain views are taboo, but not legally barred — that also seems like an issue to me. I wouldn’t call that meaningful freedom of speech.”

However, when it comes to campus attitudes about certain ideas, the question of what free speech means becomes complicated. After all, the students The Daily interviewed agreed that an important part of free speech is being able to criticize the speech of others.

“People often conflate criticism of that voice with the denial of free speech,” said Maldonado, “And that’s absurd to me … I wrote a piece on Robert Spencer and received hate mail. I felt like that was part of the game. You don’t do stuff like that unless you’re prepared to be criticized.”

Though Wolfe agreed that freedom of speech does not guarantee freedom from criticism, he said that he feels there are problematic taboos around certain issues on campus.

“If someone were to express some belief in white supremacy, they would be justly shunned,” Wolfe said. “I think it does extend a little bit too far … honestly sometimes [The Review publishes] pieces that are pretty reasonable, I think, and people default get angry.”

Many of The Review’s stories have come under fire, often for the way they interpret the concept of free speech. A recent Stanford Politics article accused The Review of baselessly claiming that the larger Stanford community fails to engage in meaningful dialogue while painting itself as the champion of such dialogue. Additionally, the article criticized The Review for publishing a story which accused Professor David Palumbo-Liu of being an Antifa leader. After the story’s publication, Palumbo-Liu received death threats.

“To feign ignorance as to how their fear-mongering portrait of Palumbo-Liu as a leader of terrorists could possibly have instigated such an attack demonstrates a perverse unwillingness to grasp how rhetorical excess degrades our politics,” commented Stanford Politics.

The article also criticized the administration for claiming that it supports free speech while failing to grapple with the tensions between free expression and inclusivity, or to truly provide a stage for a broad range of ideas. The piece specifically questioned Cardinal Conversations, a speaker series which Wolfe supports and for which Jacques served on a student steering committee.

“For issues that deserve such patient and thorough engagement with the founding assumptions of American intellectual and political history, a strange air of performance and hastiness hangs over Cardinal Conversations,” wrote the piece’s authors. “The distracting performativity of Cardinal Conversations is not helped by the show’s host and architect, Hoover Institution historian Niall Ferguson.”

Not long after this piece’s publication, Ferguson, already a controversial figure, tendered his resignation from Cardinal Conversations when emails in which he discussed the speaker series and had harsh takes on “SJWs” were discovered and made public. In one of the emails to SCR leadership, Ferguson instructed his research assistant (also an SCR member) to conduct opposition research on Michael Ocon ’20, a progressive candidate for ASSU Exec. In another, he suggested ways to intimidate non-SCR affiliated members of the student steering committee for Cardinal Conversations. Provost Persis Drell accepted Ferguson’s resignation, saying that the emails opposed the mission of the speaker series

This year’s debate around Cardinal Conversations may be part of a larger shift in campus attitudes toward free speech. Taubman noted that he has seen increased intolerance at Stanford in the past decade, and especially in the last three or four years. This intolerance stands in contrast to the campus atmosphere during the Vietnam War.

“In the period when I was a student,” Taubman said, “The cacophony on campus was very loud and shrill, but it was also a vigorous debate that was going on. People disagreed vehemently about goals, but it had to do with the goals, not the words that were used to advocate those goals. I think there’s really more focus on speech now. Speech has become a sensitive issue.”

When it comes to improving the campus climate around speech, no one The Daily interviewed said they were entirely sure what was needed. Many said they felt a need to draw lines about what rights free speech protects and what it does not, but they do not trust anyone to draw such lines. Several students thought increased introspection might help calm tensions.

“It’s a collective problem so it’s hard to change. But in general, don’t knee-jerk react to something that sounds controversial,” Wolfe said.

Contact Mini Racker at mracker ‘at’ stanford.edu.

This print version of this article incorrectly stated that the Walrus Club discussed the National Rifle Association. In fact, it discussed the National Recovery Administration. The Daily regrets this error.