Fewer than one in five eligible Stanford students voted in the 2014 midterm elections. Less than 50 percent of eligible students cast their ballots in the 2016 presidential election. Overall, Stanford trails its peer research institutions by about two percent in terms of voting rate. Why is the level of civic engagement among Stanford students so low? Amid the release of these abysmal statistics, a coalition of students, faculty and staff are responding with the StanfordVotes initiative, a collective effort to improve student voter registration and engagement on campus.

Behind the numbers

The data comes from the National Study of Learning, Voting and Engagement (NSLVE), an initiative run by Tufts University researchers who analyzed voting data from more than nine million students in 1,100 higher education institutions across all 50 states. Their published results consider enrollment data from all undergraduates, graduate students and postdocs, and match the data against publicly available state voting records.

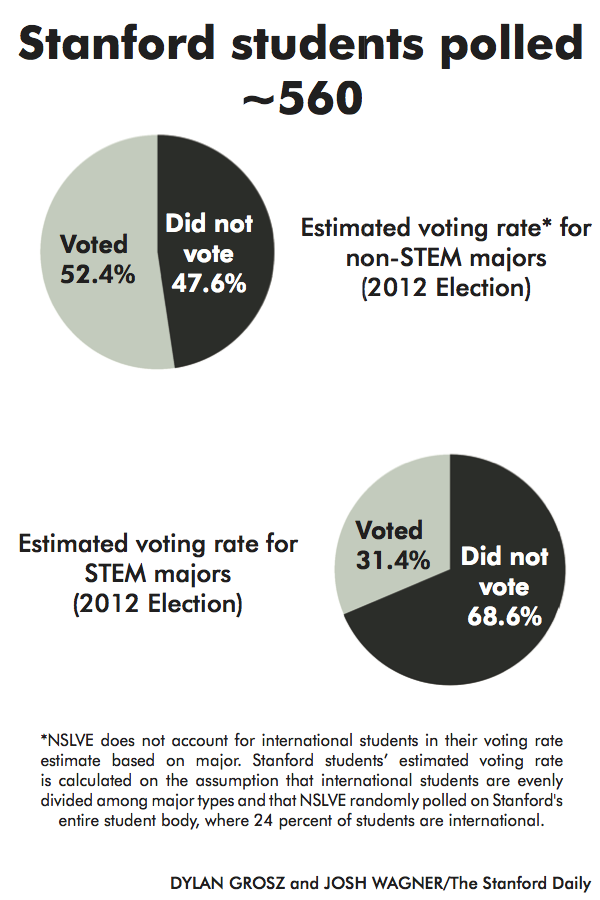

According to the study, non-STEM majors tend to vote at significantly higher rates than STEM majors. Women also tend to vote more often than men. Turnout from Hispanic and Asian students has increased significantly since 2012, while the turnout for black students experienced a decline.

Urban Studies Lecturer Larry Litvak, who collaborated with Stanford in Government (SIG) and the Haas Center for Public Service to publicize these statistics in a call-to-action published in The Daily last spring, cited a variety of reasons for the low voter turnout among college students. For one, voter participation is highly correlated with age. Younger individuals tend to have less at stake — and are therefore less engaged — in their communities compared to older generations.

“[Younger people] move around more, they generally don’t have houses, they don’t have children in school and so on,” Litvak said. “So, some of the things that would motivate political participation are not present.”

He added that there’s a strong correlation between how far away students are from home and whether or not they vote. Students who attend out-of-state institutions often have to vote absentee or re-register to vote in a new state, which can add additional obstacles to the voting process. It’s also more likely that students away from home are less informed about the candidates and ballot measures in their voting state due to their geographic separation.

“It’s not particularly easy to vote,” said Antonia Hellman ’21, co-director of SIG’s Community Service and Voter Engagement Team.

Hellman cited Michigan’s particularly stringent policies for first-time voters, which requires individuals to either vote in-person for their first elections or hand-deliver their initial registration paperwork to the city clerk in their hometowns.

It is easy for students to feel daunted by the process because they often have multiple addresses and may be voting for the first time in college, added Sara Clark. Clark is a senior partnerships associate at TurboVote, an online voter registration and reminder service that partners with universities including Stanford.

Campus voting initiatives

Under the Higher Education Act, universities are already mandated to inform students about registering to vote. But this year marked the beginning of a more concerted effort to increase voter registration and engagement at Stanford in response to the issues underlying Stanford students’ low level of civic engagement. This spring, a coalition of students, faculty and staff came together under the nonpartisan StanfordVotes initiative, a project that includes both bottom-up and top-down mechanisms to increase voter engagement in the upcoming Nov. 6 midterms.

According to Megan Fogarty, deputy executive director at the Haas Center, StanfordVotes is taking a three-pronged approach in its effort to galvanize college students to vote. The first effort area focuses on easing the voter registration process for eligible students and staff, especially with regards to requesting absentee ballots. TurboVote’s partnership with Stanford in Government and the Haas Center helps streamline the process of registering students to vote.

The second prong involves building a campus message around the importance of voting through online reminders on Axess, flyering campaigns, speaker events and more.

“There’s a lot of [campus] emphasis on social impact and volunteerism, but that’s not the same as civic participation [in] voting,” Litvak said, pointing out that University culture plays a significant role in encouraging student political engagement.

To that extent, history professor Allyson Hobbs emphasized the role of faculty in contributing to a campus message that emphasizes the importance of voting. A variety of courses on voting issues are currently being offered in departments ranging from political science to psychology.

“This is a really critical aspect of our interactions with students and in what we’re teaching students and what we’re discussing in our classrooms,” Hobbs said. “It’s really important for faculty to convey to students the importance of voting and the importance of being part of the political process.

StanfordVotes’ community messaging initiative also involves SIG’s 65 Civic Engagement Volunteers (CEVs), who will spend two to four hours a week for the first half of fall quarter raising awareness about voting through student organizations and other campus communities. SIG Chair Olivia Martin ’19 added that several CEVs are in fact STEM majors, a reflection of SIG’s efforts to address the disparity in voter participation between STEM and non-STEM students.

The final piece of the puzzle, according to Fogarty, involves working to remove obstacles to voting, particularly those unique to out-of-state college students. SIG and the Haas Center are currently working on hosting a mailing party in White Plaza before Election Day to help students mail their absentee ballots on time.

Challenges at stake

Despite the mobilization efforts underpinning StanfordVotes, there remain a number of challenges facing forward in the push to increase student voter engagement at Stanford. According to Hellman’s co-director Christina Li ’21, Stanford’s later quarter system start date poses a challenge given its proximity to the Nov. 6 election.

“It’s just a matter of weeks and days before you have to get registered to vote and before you have to go out and vote yourself,” Li said. “We can’t just roll this initiative out slowly, we have to hit the ground running.”

Hellman added that despite efforts to encourage voter registration, it’s ultimately up to students to take it upon themselves to get to the polls on Election Day.

“It’s one thing to get people registered, help them through the process — we can do that,” she said. “There’s only so much we can do, however. In the end, it’s really up to them.”

Nationally, there’s a lot at stake in this year’s midterms. According to the New York Times, over 30 competitive House races this year were won in 2016 by margins smaller than the number of college students living in the district. Democrats have a real shot at taking back the House of Representatives and, according to historian and professor Estelle Freedman, there’s been a recent revival of civic engagement in response to the current state of American politics.

“Quite honestly … we are in a moment of democratic crisis in terms of the undermining of voting rights, the possibility of foreign interference in elections [and] the loss of truthfulness,” Freedman said. “I’m hard-pressed to think of a midterm that might be as significant as this one.”

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu and Claire Wang at clwang32 ‘at’ stanford.edu.