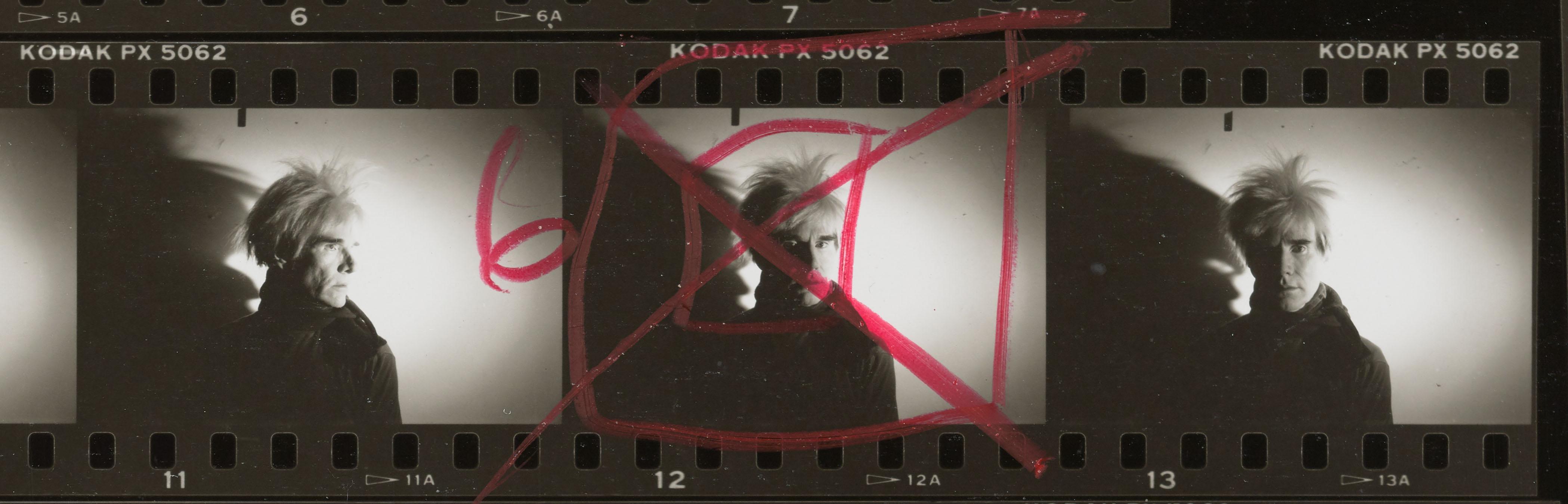

Even during his lifetime, the artist Andy Warhol was associated with an astute adage. “In the future,” he proclaimed, “everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.” He soon became so tired of saying the line that he changed it to “in 15 minutes, everyone will be famous.” Warhol’s truisms, however, do not seem to describe his own oeuvre. Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans and Marilyn Monroe portraits have fascinated viewers for 50 years, not 15 minutes. “Contact Warhol: Photography Without End,” an exhibit now open at the Cantor Arts Center, demonstrates that not all of Warhol’s work has become world-renowned. The show, co-curated by Professors Richard Meyer and Peggy Phelan, features hundreds of Warhol’s contact sheets, many of which have never been seen before. During the last 11 years of his life, Warhol was a prolific photographer. The contact sheets display the plethora of pictures that he took. While some of the sheets are pristine, Warhol would make markings on others, indicating which photos he wanted to print or blow up.

The exhibition does not treat these contact sheets as artworks in and of themselves. Instead, curators Meyer and Phelan examine how they informed Warhol’s work in various media. Ultimately, “Contact Warhol” illuminates the creative process of this crucial pop artist.

Most of the images on the contact sheets were never intended for publication. Warhol published a few pictures in “Andy Warhol’s Exposures,” a 1979 book he co-authored with assistant Bob Colacello. The photographs were meant to illustrate Warhol’s severe case of “Social Disease.” As he explains in the book, he must “go out every night” and bring along a tape recorder and a camera. Partying is a Herculean task because he socializes with celebrities. Sometimes these parties do yield real work. Warhol tries to seek out stars who want their portraits done. Yet, even if Warhol is unsuccessful at receiving a commission, “having a few rolls of film to develop gives [him] a good reason to get up in the morning.”

Warhol’s actions at parties upset traditional notions of photography. While other photographers like Richard Avedon try to capture the glamour and grace of the elite, Warhol wants to show “a famous person doing something un-famous.” Therefore, Warhol photographs Bianca Jagger pretending to shave her underarm and Liza Minnelli simply waiting around Studio 54. Furthermore, Warhol is not constantly behind the camera. Often, he would simply give the camera to an assistant and mingle with the guests. Therefore, many images on the contact sheets show Warhol in the company of such illustrious figures like Jagger and Minnelli.

In “Exposures,” Warhol brags that he will go to any social event— “the tail end of a cocktail party,” a gathering in Studio 54, “a SoHo opening, a Broadway opening, a boutique opening, a restaurant opening,” even the opening of a toilet seat. Indeed, the contact sheets show that Warhol’s activities were multifarious. On one contact sheet, he takes a few pictures of Isabella Rossellini at a party. Then, he abruptly begins to photograph gay men having sex. On another, the object of his gaze quickly shifts from the lauded writer Truman Capote to a large watermelon. A digital display in the gallery allows visitors to sort through all the contact sheets and find similar jumps.

Yet, regardless of their subject matter, these images often served as a source of inspiration for Warhol. The paintings that Warhol produced from these pictures hang directly above the contact sheets. Visitors can see how Warhol transfigured these images into art. For example, his alchemic process becomes apparent when his poster for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Querelle” is juxtaposed with the photograph that served as the basis for its design. The contact sheet contains multiple pictures of male models, but he chose a particularly provocative shot for the poster. It depicts two young men bare-chested in profile. One has his tongue on the other’s neck.

In creating the poster, Warhol directed attention to the tongue by painting it a stark scarlet. In fact, the crimson seeps out of the lines demarcating the tongue, as if to suggest that the impact of this strange gesture defies the law of nature. Warhol drew sketchy lines around the two figures, and the image abruptly cuts off, leaving negative space on the right-hand side of the poster. Ultimately, Warhol leaves the impression that the image is unfinished. Before Warhol made his poster, Fassbinder died. He was only 36, and we can only imagine what films he would have made to fill empty screens everywhere. Ultimately, Warhol transformed a photograph into a comment on the work of another artist.

“Contact Warhol” not only reveals that Warhol’s brilliance extends beyond Campbell’s Soup Cans and portraits of Marilyn Monroe, but also demonstrates that his prolific genius did not come effortlessly. He had to take hundreds of photographs before he alighted on one that could be published or used as inspiration for a painting. Warhol always liked to claim that when he went to parties, he was working. He claimed that he could “make all play work.” “Contact Warhol” supports that claim. Andy Warhol worked to make his 15 minutes of fame into an eternity.

Numerous events related to the “Contact Warhol” show will take place this weekend. For more information, please visit https://museum.stanford.edu/exhibitions/contact-warhol-photography-without-end.

Contact Amir Abou-Jaoude at amir2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.