At the end of the 1942 melodrama “Now, Voyager,” Bette Davis’s lover asks her if she has everything she wants. She falls into his arms and chides him, “Oh, Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”

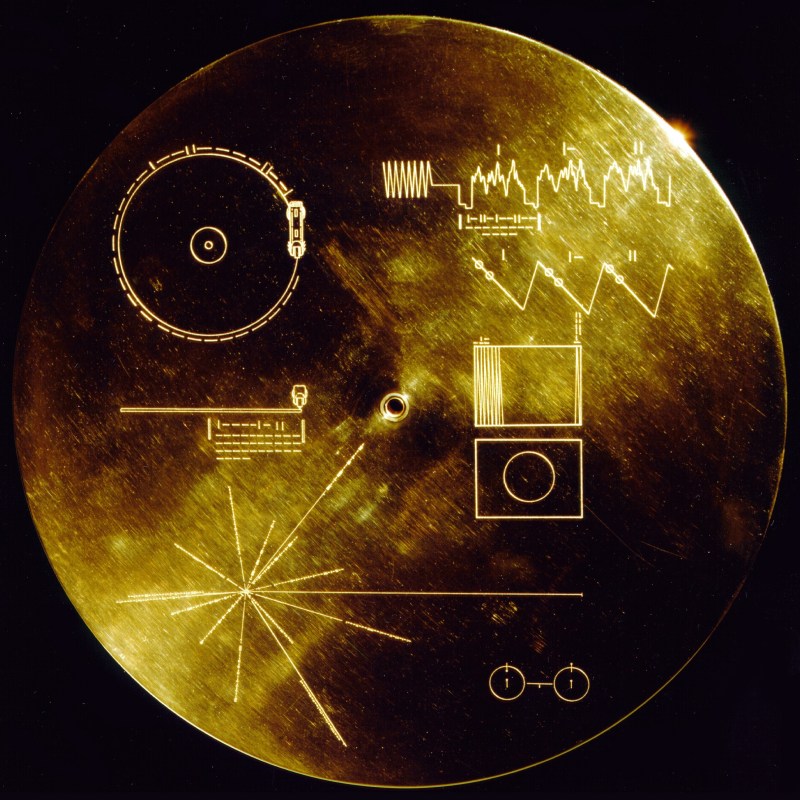

In the early 1970s, NASA stopped asking Congress for funding to go to the moon and turned its attention to the stars. The planets were perfectly aligned to conduct a grand tour of the universe. This project culminated in the launch of the Voyager probes in 1977. Voyager 1 visited Jupiter, Titan and Saturn, while Voyager 2 traveled to Uranus and Neptune. After their planetary missions were complete, the probes continued into interstellar space. In 40,000 years, the spacecraft will be closer to the star Alpha Centauri than the sun. When the Voyager probes were launched, the scientist Carl Sagan realized that they would traverse myriad solar systems. Therefore, he wanted to include a message from Earth that would facilitate contact with extraterrestrial life. Sagan recruited journalist Timothy Ferris and radio astronomer Francis Drake to compose a message. They created a golden record and affixed it to the probes. Ferris curated the musical selections on one side of the record. On the reverse side, Drake encoded 118 images onto the disc.

Ferris and Drake discussed their work on the record in a conversation sponsored by the American Studies program and moderated by Professor Elizabeth Kessler. They described the choices they made in compiling the record, the challenges of sending it into space, and the reception it received on Earth. The event elucidated the significance of the record. It is not simply a message sent to the stars, but an optimistic vision meant to inspire those on Earth.

The playwright Arthur Miller once observed that great civilizations rise and fall, and “what do we have left of it all but a handful of plays, essays, carved stones and some strokes of paint on paper or the rock cave wall – in a word, art?” The committee that produced the record only had eight weeks to finish their work, but they were aware that their creation would outlast all of them. The golden record would remain intact for two billion years, long after the demise of humanity. If aliens were to find the record in the far future, it would serve the same function that art fulfills for us. It would provide them insights into the mores of an antique culture.

Therefore, Ferris strove to make a “good record,” while Drake worked to create a comprehensive slideshow. Although the Voyager project was an American initiative, they felt the record should reflect the whole world. Ferris included music from a variety of different traditions, while Drake ensured that people of all nationalities were visible in the images. Both acknowledged that religious beliefs have played a crucial role in shaping society, but no hymns or icons are included on the record. There was only a finite amount of space, and it was impossible to represent every denomination.

Furthermore, they chose to concentrate on cooperation between people, not conflict. The golden record paints a rosy portrait of Earth. The only pictorial sign of warfare is the battlements that surround the Great Wall of China. While dissonant pieces like “The Rite of Spring” were selected, even these were chosen to illustrate collaboration between culture. Ferris juxtaposed Stravinsky’s melody with African folk music, and he hoped aliens would recognize that both possessed the same pulsating rhythm.

Yet, some of the curatorial choices were more prosaic. For example, in selecting the pictures, Drake had to approach each one through the eyes of an extraterrestrial. How would aliens that look like a bipedal squirrel or a 14-legged spider perceive these photographs? Initially, Drake wanted to include a picture of Mikhail Baryshnikov and a ballerina dancing. The image of two people gracefully intertwined seemed poetic, but the photograph could confuse aliens. Baryshnikov and his partner are so close together that extraterrestrials could perceive them as a bestial being with two heads. Therefore, the picture was not chosen for the record. Drake feels that even some selected images are not clear enough. A spectacular photograph shows dolphins jumping in midair, but although it may be awesome, it is also ambiguous. An alien unfamiliar with animals could infer that Earth features a fleet of flying fish.

In adopting this approach, Ferris and Drake became artists. The critic Viktor Shlovsky wrote that the artist’s power is “to make the familiar seem strange … to describe an object as if he were seeing it for the first time.” While extraterrestrials might never find it, terrestrials would certainly see it. Yet, although humans would be familiar with worldly customs, Ferris and Drake are still proliferating a strange vision of the Earth. People do not usually exchange greetings in different language or consider how a Western monument of musical modernism draws on the rites of another culture. News photographs, unlike those on the Golden Record, rarely depict people coming together across political boundaries. Instead of contemplating the magnificence of the dolphin, humans wreak havoc on its habit. Ultimately, the Golden Record does not reflect the actual Earth, but the aspirations we have for our planet.

Ferris and Drake made clear that the record is intended for extraterrestrial consumption. Ferris stated that the “worst-case scenario” would occur if aliens did not retrieve it and it floated adrift in space forever. Still, perhaps Bette Davis is wrong. The Golden Record does not have to have the stars in order to be relevant. Forty years after it was dispatched into deep space, it reminds us of the wonderful world we could construct right here.

Contact Amir Abou-Jaoude at amir2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.