There is, perhaps, a feeling like no other as the morning greets you with a world of freshly fallen snow. You open the window or the door to find that the white stretches everywhere. Sound is muffled, and nothing moves.

Yet I say perhaps, because I do not know. I am from San Diego and have never experienced what I’ve just described. I can only imagine what it must feel like, that stillness, that quiet, that cold. There is no real memory of this that exists for me.

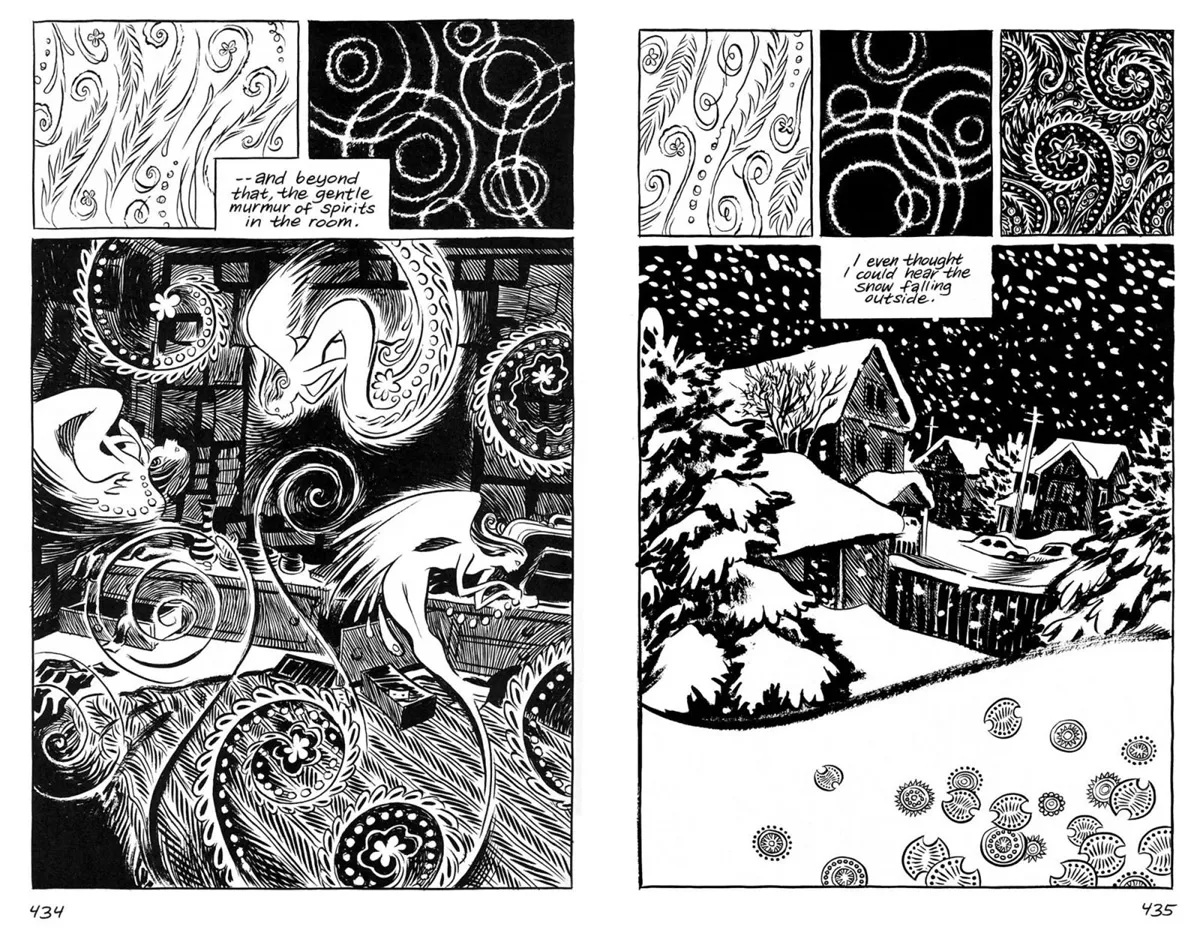

Craig Thompson’s graphic memoir “Blankets” traces moments from his childhood through high school. The book begins by exploring Craig’s relationship with his younger brother and then follows different threads of his early life: being raised by extremely religious parents, going to Bible camp and not really fitting in, and falling in love with a girl named Raina. Though Craig and Raina start dating at camp, they live far apart and eventually break up. Much of Craig’s focus is his experience with religion and love, and the conflicts between faith, personal morality, sexuality, desire and responsibility. But for me, these are all secondary to a theme of processing memory. How do we understand our memories? How can we move on from the past? How do those memories shape who we are? How do we shape ourselves based on the memories we have, especially traumatic ones?

I will say immediately that Thompson does not give answers to these questions. I do not finish the novel knowing. Actually, I finish the novel not really even knowing what to think, or how to think. Rather, I am immersed in feeling. “Blankets” is one of its own titular objects – the language and art wrap around me as I read, muting the harshness of the outside. Thompson takes me in and makes me experience the memories, the cold, the internal conflict. It’s honestly hard to describe. (I’m clearly struggling here – how do I express with words what art does to the way I feel, without destroying that very feeling with particularities?)

This blanket does not always protect us, for there are moments when the past is too present to be warded away. Memories haunt Craig, an experience represented masterfully by the reproduction of the same images in new contexts throughout the book. Thompson captures not only his character’s memories but the process of remembering: how present events trigger the past in ways sometimes unexpected.

Scott McCloud, in his landmark “Understanding Comics,” says that, “No other art form gives so much to its audience while asking so much from them as well.” What he means is that comics require “closure”: From panel to panel, the reader must make the connections. In this way, comics are immersive because of the work they need to make sense. If done effectively, McCloud argues that we get sucked into the story without realizing our subconscious effort to make that happen. This is how I see “Blankets.” Images appear throughout the novel that do not, on face value, make sense in their contexts. But as you read, you realize these images are actually memories, flashbacks from Craig’s past. This realization is an act of closure by you because you are the one telling the story – Thompson is just giving you the images. You are immersed; you are Craig, constructing a narrative out of random moments.

There is a beautiful scene in which Craig and his first girlfriend Raina are separating after spending two weeks together. They are deeply in love, as only first loves can be, and it is the last time they will ever see each other. They first pull up in the parking lot of a diner, and the image is drawn with shadows. The parents exchange greetings, the teenagers exchange farewells. Again, we see an aerial view of the diner and the parking lot. But now, everything is white. There are no shadows, and only the outlines of the buildings and vehicles give us a sense of where we are. The snow encompasses and swallows everything. Raina’s car pulls out of the parking lot and we feel with Craig the muteness he must feel, the muteness of the snow and the loss of the girl he loves.

And then, when you turn the page, Raina’s tiny car falls off the edge of the world.

At the end of the novel, Craig comes back to his childhood home and digs up a quilt Raina had sewn for him several years ago. He uses the blanket to sleep that night. Thompson writes:

“That night was colder than the last, and the extra layer – held close to my body – was just what I needed. Sometimes, upon waking, the residual dream can be more appealing than reality, and one is reluctant to give it up. For a while, you feel like a ghost – not fully materialized, and unable to manipulate your surroundings. Or else, it is the dream that haunts you … “

Thompson’s writing poetically captures what it is like to hold on to memories, to cling to the past. They are like blankets “held close,” and the comforting dreams they offer can be “more appealing than reality.” This, perhaps, can be stifling; how do we escape the dream, and continue to live, awake?

“But the act of waking is dependent on remembering.”

In the final pages, Craig wakes up in the morning. It’s Christmas. He tells his family that he’s going on a walk. It starts off slow. Soon he picks up the pace, and it escalates into a romp in the snow. He stops and his footprints are deep and dark, disrupting the pure sheet of white like ink spilled onto an empty page. His footprints scar the snow just as Thompson’s art marks the pages of his graphic novel. Through both instances of intentional remembrance, an ephemeral memory becomes eternal.

Contact Lily Nilipour at lilynil ‘at’ stanford.edu.