Sports statistics make a convincing case for Stanford’s athletic superiority over Berkeley. These Bay Area rivals have faced off on the football field 120 times. Stanford has won 63 Big Games compared to Berkeley’s 46. (Eleven times the game ended in a tie.)

Still, the Stanford-Berkeley rivalry extends far beyond the football field. If Stanford is clearly dominant in athletics, perhaps Berkeley has made a larger contribution to the arts. Compare the lists of notable alumni. Errol Morris was a Bear, and his documentary “The Thin Blue Line” freed an innocent man from prison. (Granted, Morris called Berkeley “a world of pedants.”) Robert Penn Warren, author of “All the King’s Men,” won three Pulitzer Prizes after receiving a Master’s from Berkeley. John Steinbeck may have been a greater writer, but Stanford refused to award him a degree.

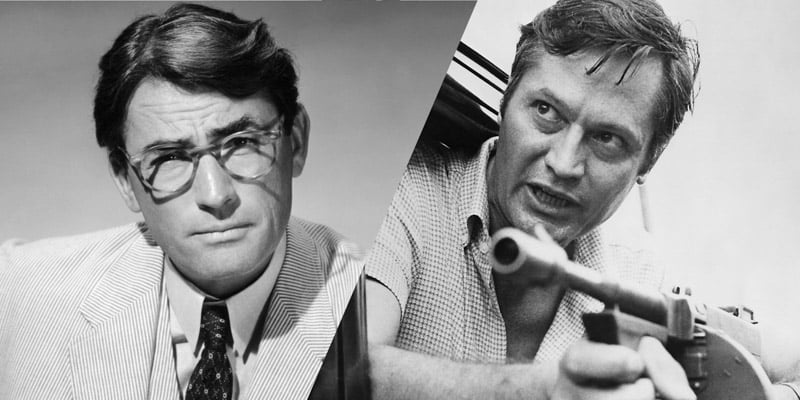

Berkeley is the alma mater of great actors like Gregory Peck. By contrast, the most significant cinematic luminary to attend Stanford is the producer Roger Corman. Peck starred in prestigious films like “Spellbound,” “Cape Fear” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Corman’s ventures were less likely to attract critical acclaim. His oeuvre includes some schlocky adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories and a surfeit of surfing films. The titles of his films belie their quality— for example, “I, Mobster,” “Ski Troop Attack,” “Teenage Caveman” and “Hot Car Girl.” As a devotee of classic film, I admire Peck’s craft. As a member of the Cardinal, however, I feel compelled to defend Corman. Still, considering Peck and Corman in tandem suggests that perhaps the divide between Cardinals and Bears is not unbridgeable. Experiences in college may have laid the foundations for their careers, but ultimately, both made invaluable contributions to the cinema.

Peck arrived at Berkeley amid the Great Depression. He aspired to become a doctor, but during his first semester, he flunked calculus and chemistry. Because of this, he changed his major to English. Peck’s new goal was to earn a Ph.D. and work at a university. As he explained in an interview years later, he wanted to “teach at a place like Berkeley because [he] so loved the college and [his] time there.” Peck abandoned his plan, however, when he “stumbled into the acting thing.” Berkeley had no theater department in the 1930s, but Peck appeared in a student production of Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata” and a theatrical adaptation of Melville’s “Moby Dick.” By the time he left Berkeley in 1939, he had become an accomplished actor. After several years working on Broadway, Peck came to Hollywood in 1944. His performance in “The Keys to the Kingdom” was nominated for an Academy Award in that year. He was a star almost immediately.

In 1950, Peck agreed to star in a Western, “The Gunfighter.” A young writer named Roger Corman had edited the screenplay. Corman had recently graduated from Stanford. Although he received a degree in engineering, while at Stanford, Corman realized that he wanted to pursue a career in entertainment. He was a film critic for this paper (The Stanford Daily), so he got free passes to the movies. Then, he “started to analyze the pictures [and] look at them more closely.” Ultimately, he concluded that making movies was “what [he] wanted to do.” After college, he moved to Hollywood and began working at Fox. Yet, when Fox executives refused to give him credit for his contributions to “The Gunfighter,” he quit. He resolved to make low-budget movies on his own. At the same time that the executives denied Corman credit, they gave Gregory Peck top billing in the film.

In some sense, “The Gunfighter” exemplifies the difference between Peck and Corman’s careers. Peck could dominate every frame of a film. This tall, commanding figure projected authority. Peck’s performance as Atticus Finch in the film “To Kill a Mockingbird” is the finest expression of his screen persona. He talks slowly, with a slight Southern affect that befits his Alabama milieu. When Atticus defends a wrongly convicted man in court, Peck does not descend into histrionics. He maintains the same even tone. His gestures are sparse and understated. His brow furrows. He powerfully eviscerates the institutionalized racism of Atticus’ society, but he is not afraid to let uncomfortable questions linger. In most movies, lawyers bluster through an argument, begging for the audience’s attention. Peck does not need to make grandiose movements to rivet viewers. Indeed, his performance is so transfixing that Harper Lee herself maintained he wasn’t acting. When Peck played Atticus, she asserted, “he had played himself.”

Corman’s craft is much less visible than Peck’s. Any viewer can appreciate Peck’s eloquent statements on human rights. Yet, the value of “Boxcar Bertha” is more obscure. The film, which Corman produced, tells the story of two amorous fugitives who become involved in a railroad strike. At one point during the film, the lovers reunite. The camera remains static during their meeting. Then, the police come in, and the camera begins to move so erratically it almost induces nausea. The direction here may seem amateurish, but the auteur of this film is now regarded as a genius. Because he could make films cheaply, Corman was able to give young directors like Martin Scorsese a chance. Without Corman’s support, Scorsese may have never been able to make films like “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull” or “Goodfellas.” Corman also mentored Francis Ford Coppola, who made “The Godfather” and “Apocalypse Now,” Peter Bogdanovich, who directed “The Last Picture Show” and Jonathan Demme, who helmed “The Silence of the Lambs.” When watching “Taxi Driver,” “The Godfather” or “The Silence of the Lambs,” Corman’s campy creations do not immediately come to mind. Yet, because Corman allowed these talents to work on films like “Dementia 13,” “Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women” and “Angels Hard as They Come,” he ensured that they could play an essential role in the American cinema.

In the lead-up to the Big Game, the stories of Peck and Corman remind us that the relationship between Stanford and Berkeley is multifaceted. Just as we revel in Peck’s magnificent acting, we can delight in the rhetoric of collegiate rivalry. Yet, just as we must dig deeper to uncover Corman’s significance, we should also consider the less prominent dialogues between the two universities. After all, if we only went by the superficial record books of the past, Stanford would be a clear favorite to win the game. But if things were already decided by history, why would we even play the games?

Contact Amir Abou Jaoude at amir2 ‘at’ stanford.edu