When I was six years old, the bookstore in my hometown closed. My only memories of the shop are a display of cat magnets near the front register and a small wooden table stocked with paper and crayons. I would sit at the table for hours on end, hoping to create a drawing great enough to be taped to the bookstore’s wall. My mom says she took me to the store nearly every afternoon and let me pick out stacks of picture books for her to read to me.

During the summer before my senior year of high school, a new bookstore opened just a few stores down from the shop I used to visit as a child. It seemed only logical that I apply to be a bookseller. I got the job and started working a month later.

By the time I left for Stanford, I had spent hours and hours at Belmont Books. In some ways, my job was exactly as I anticipated. I spent my time shelving books, operating the cash register, offering recommendations to customers and writing my own book reviews to place around the store. I even helped set up a drawing station not unlike the one I loved when I was a child, and this time I got to choose which paintings to tape to the wall.

But when I first applied to be a bookseller, I didn’t realize the amount of time I would spend not only assisting customers but also learning from them. I’ve always been fond of observing others — I could spend hours people watching in a busy cafe — and my position behind the bookstore checkout desk turned out to be an unexpectedly great place to people watch.

As more and more time passed, I began to recognize repeat customers and notice patterns in their book-buying behaviors. I was familiar with the term “book person” before I began working, but I had always considered it a binary definition: You’re either a book person, or you’re not. The more I worked at the bookstore, the more I began to understand the many different ways to enjoy a book.

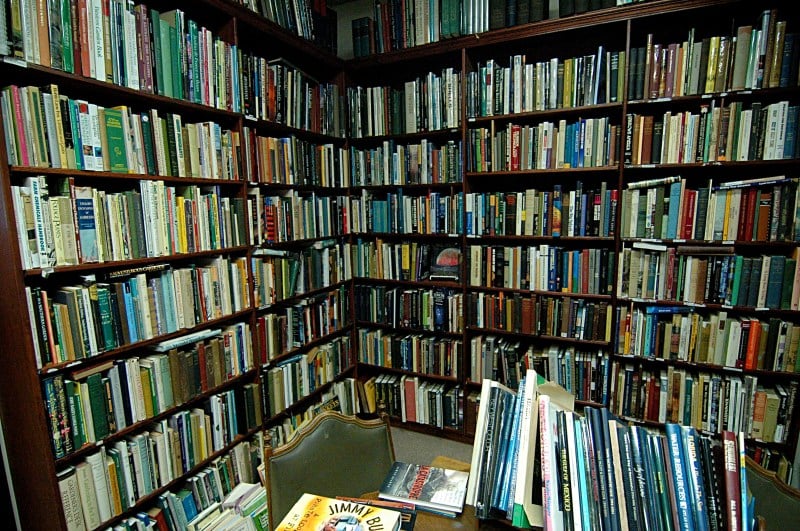

Some customers entered the store at odd hours when the bookstore was nearly silent and walked reverently through the aisles, stopping occasionally to read the back of a novel that caught their eye or fix a book that seemed out of place on the shelf. When these customers eventually made their way to the cash register, they often spent another thirty minutes talking with whomever was working, discussing everything from their weekend plans to the reasons they had chosen the books they were buying. They didn’t buy books very often, but each purchase was clearly meaningful, and the bookstore meant more to them than a place to obtain books; visiting the bookstore was an experience.

For others, the bookstore was one checkpoint on a long to-do list. These people rushed through the front door, marched to the cash register, announced the name of the book they were looking for and left within five minutes. They always knew exactly which book they would purchase before they walked through the door. They were avid readers — some of them returned to the store just a few days after purchasing the previous novel. While I rarely interacted with these customers for more than a few minutes, it was clear that they too loved books. They always knew the most recent releases, they could rattle off books similar to the one they were purchasing if someone asked for a recommendation, and they appreciated my town’s local bookstore enough to purchase books from us instead of a larger retailer with lower prices.

There were other moments that still resonate with me. I once watched one customer read the first page of 15 different books and then leave empty handed. I once observed a little boy devour every book about trains and then throw a tantrum when his mother suggested he try out a book about cars instead. I once helped an anxious grandmother select books to gift to all of her grandchildren, even though she struggled to read in English herself.

I eventually began to understand that all of these people were “book people,” even though they enjoyed different types of books and bought different amounts of books. Reading played a different role in all of their lives, but at the end of the day, each customer appreciated the power of a story, and that I think is all that really matters.

Unsurprisingly, after spending so much time thinking about how other people read books, I began to evaluate my own habits. I had decided how to characterize many of the customers who entered the store, but what kind of book person was I? The answer ended up being much less straightforward than I expected.

I love bookstores. I could spend days scanning shelves, reading the little book recommendations that staff members leave and flipping through the first pages of whichever book’s cover catches my eye. I also meticulously research books before I read them, rarely buy a book I haven’t previously heard of and often hesitate to share my book recommendations with others for fear that my choices aren’t interesting or prestigious enough. On some days, I love carefully working my way through a difficult text, but on some nights, all I want to do is curl up with an unapologetically predictable and cliched novel. In short, as a reader, I fit into several of the categories I identified in customers, and I think this discovery only reinforces my new understanding of the diverse ways to enjoy a good story.

While working at the bookstore, I learned that there is no “right” way to read a book. There are no good books or bad books. There are no true readers or fake ones. There are only books and the people who read them. This, I believe, is part of what makes reading so special.

Contact Sofia Schlozman at sschloz ‘at’ stanford.edu.