Contributing to the advancement of scientific research doesn’t always mean conducting experiments in state-of-the-art laboratories. In fact, one way to help solve questions in science is designed for almost anyone: playing video games — more specifically, scientific discovery games (SDGs).

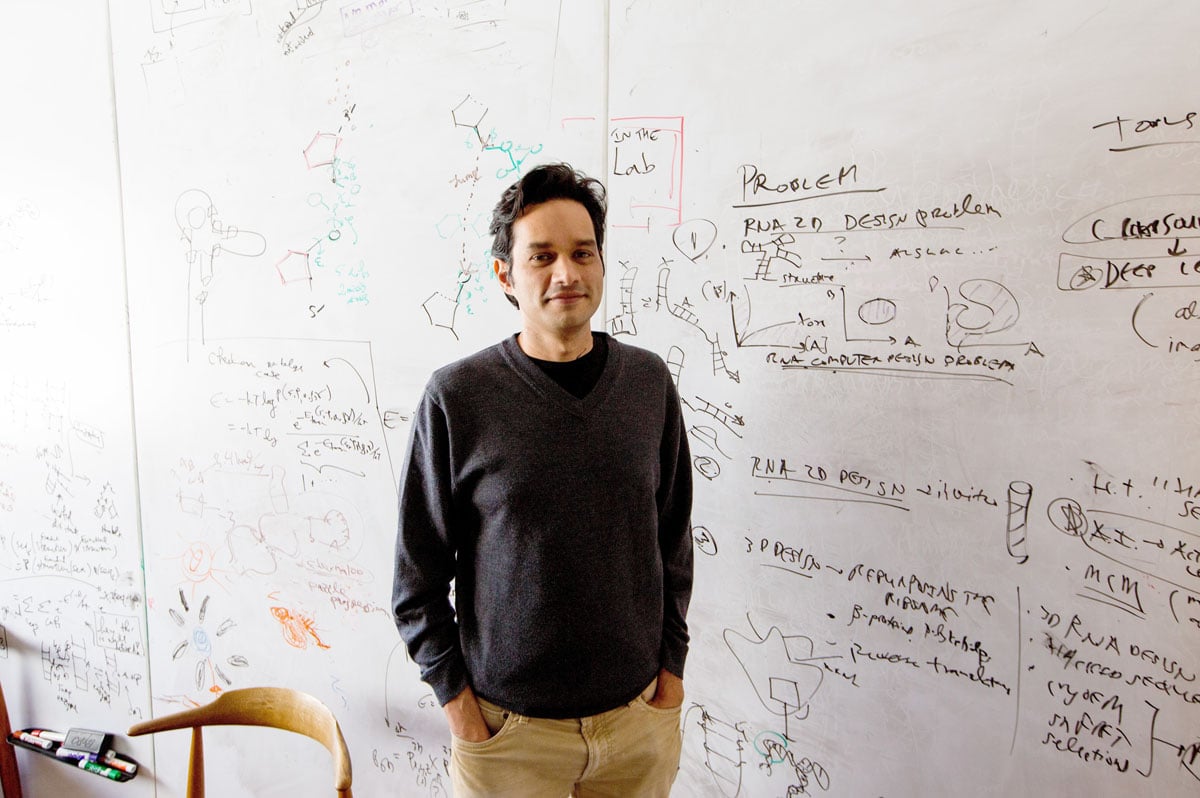

Associate biology professor Rhiju Das and assistant bioengineering professor Ingmar Riedel-Kruse discussed scientific effectiveness, player communities and costs of developing SDGs in a review published on July 2 in the Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science. Both Das and Riedel-Kruse have developed early SDGs and platforms for playful interactions with living microbiology.

Focusing on educational games, Riedel-Kruse has developed biotics games in which players can interact with microorganisms. One such game is Pac-Mecium, a spin-off of Pac-Man in which players guide paramecia, a common genus of unicellular ciliates, to eat little dots.

As for Das, he has reached out to the creators of Foldit — widely considered the first SDG — to develop an RNA version of Foldit. In doing so, Das and his lab developed EteRNA, an online puzzle game where players are challenged to design molecules for RNA-based medicines, unlike proteins in Foldit.

By completing more challenges, players can earn the privilege of having their virtually-created RNA molecules sent to Das’s lab to be synthesized in real life, where players can then get experimental feedback on their designs. Immersing themselves in the scientific problems they are helping to solve, EteRNA players have begun writing their own peer-reviewed manuscripts and have organized their own yearly Eternacon convention at Stanford. There, players and scientific researchers alike convene to discuss their progress with Eterna. Since its release in 2011, EteRNA has engaged over 200,000 players.

“What I find interesting is that the community of players who have stuck with EteRNA have done astonishing things … now, there are citizen scientists or independent scientists who are doing that and often what makes that happen is this community where players are going to talk to each other and they can run experiments on EteRNA,” Das told The Daily.

Using games as a platform for solving questions in science has brought in people from outside of the traditional scientific community, Das said.

“I would say all the top players [of EteRNA] have little or no connection to science,” he added. “I think it’s just striking how many brilliant people that are in the world, who could be scientists. They are well suited to the idea of making predictions about nature. And then finding out if they’re right or wrong. They love it as much as I do and my lab does. And they’re better at it than us, but they didn’t jump through the hoops to become professional scientists. I think those are the folks who are finding a way to contribute to science through EteRNA and other scientific discovery games.”

This approach to scientific research can speed otherwise time-consuming biomedical research, in which players have been shown to outperform existing computational prediction algorithms, according to Das and Riedel-Kruse’s review. In the case of EteRNA, heuristic rules discovered by players were turned into a predictive algorithm called EteRNAbot which had outperformed all existing algorithms.

“We started to see that these RNA molecules that our players were designed, they look close to perfect in our experiments,” Das said. “In the same kinds of challenges to make an RNA that folds up into like a snowflake shape, when we had used computer algorithms that have been developed over the previous 30 years, they didn’t fold up properly. So there’s something special going on here and it seemed that the players had been learning from all the cycles of experimental feedback.”

As SDG players make genuine scientific contributions, Das and Riedel-Kruse have raised ethical questions regarding the compensation, privacy and well-being of these players, as gamers face potential addiction, harassment and feelings of incompetence.

What makes these questions challenging to answer, the researchers argue, is that SDGs involves a new domain of science called gamified, crowdsourced citizen science — projects that divide work among a very large number of non-expert volunteers to carry out biological research through games. Crowdscourcing is a recently coined term referring to the solicitation of information and/or resources from a large group of people.

Companies such as Amazon have turned to crowdsourcing for some projects, as it can lower the cost of labor and accelerate innovation and problem solving. But with crowdsourcing being a relatively new practice, there are not many guidelines and regulations in place.

“What we’ve been thinking for a while is that what’s happening on EteRNA is really unique,” Das said. “There’s no precedent for it. For nearly all of our scientific discovery papers from EteRNA, we had EteRNA players or participants, as co-authors and as a consortium author. And so we consider the community as a community of research collaborators.”

“But some folks have argued that in scientific discovery games, the players should be considered as research subjects, like they are part of the experiment,” Das continued. “There’s a worry that we’re exploiting players for their labor. And so people are saying, for citizen science, particularly at the internet scale, as these products are getting closer and closer to economically valuable things like patentable molecules: What’s the framework needed? Or how should we think about players? And I’ve always felt that we don’t quite know the answer.”

Some argue that SDG players, who work to carry out scientific activity, should be perceived as researchers, and therefore are entitled to compensation. Others argue that the players are research participants, as researchers design gamified research protocols and conduct experiments to determine which of the protocols are effective at capturing the interest of players.

“We have very specific roles in our current system and the way we think about the relationships to professionals and amateurs in the cognitive science,” said David Magnus Ph.D. ’91, a professor of medicine and biomedical ethics and pediatrics and medicine, who presented a paper on the ethics of citizen science and gamification that was published earlier this year in the Hastings Center Report.

“There are ways in which [SDG players] do not fit easily into any of these categories [researcher, lab technician, research participants, etc.],” Magnus said. “But there are ways in which they have aspects of each of those. There are some ways in which they’re like subjects; some ways that they’re like researchers; some ways in which they’re like technicians; some ways in which they’re like just regular game players. And we need to understand a little bit of all of those norms, and we really need a community based new set of arms for understanding this kind of activity.”

It is important to take game players’ opinions into consideration, Magnus said, adding that meetings between researchers and game players can be a step forward in answering ethical questions, as game players are given a chance to voice their opinions of how they think of themselves in scientific research.

“One of the reasons why I don’t think it’s right to think of them as just research subjects is because that’s not how they think of themselves,” Magnus said. “And I think it just doesn’t capture the actual lived experience of what the game players are engaged in. At the same time, I don’t think it’s fair to say they’re just game players because the contributions to science are an important part of why they’re playing.”

Meetings between researchers and game players help establish a standard of how players are treated, Magnus said, and serve as a model for other crowdsourcing projects.

“Having a mix of scientists and non-scientists collaborating in these kinds of efforts is really important for fostering and creating a community,” Magnus said. “Then [we are] using that as a venue for something a little bit more structured, where you actually have the effort to try and do some kind of deliberative stakeholder engagement process to develop a set of norms for how these questions should be answered and really work all that out. I think doing that as a model is a good first step.”

Ethical questions remain to be answered, and efforts such as annual conventions where both scientists and players SDGs meet for discussion are working to pave a path to developing appropriate guidelines for these players. Scientifically, gamified, crowdsourced citizen science brings about new opportunities for greater participation in science to make new discoveries and advancements of science.

“We have a list of next challenges that are just getting harder and harder and a real moonshot level challenge that, if successful, could really transform medicine,” Das said.

“In terms of ethics,” he added, “I think the next steps are ensuring that players who are not Stanford scientists have a voice and have elected representatives and have a power, for example, to make the player community go on strike if they don’t agree with choices. I think there’s a huge amount of power that is in the player communities that can be and should be organized if we’re going to move these scientific discovery games forward an ethical way.”

Contact Rachel Wu at rwu2579 ‘at’ gmail.com.