“You, the first person to read this, are temporarily in charge of this shelter. You should begin the immediate-action program outlined on the following pages to protect yourself and others who follow you into this shelter.”

This is followed by a list of instructions: check incoming people for nuclear contamination, establish medical aid areas, set up a communications center. No, it’s not from a new dystopian novel — it’s taken verbatim from a 1960s fallout shelter management guide provided by Stanford to the shelter managers.

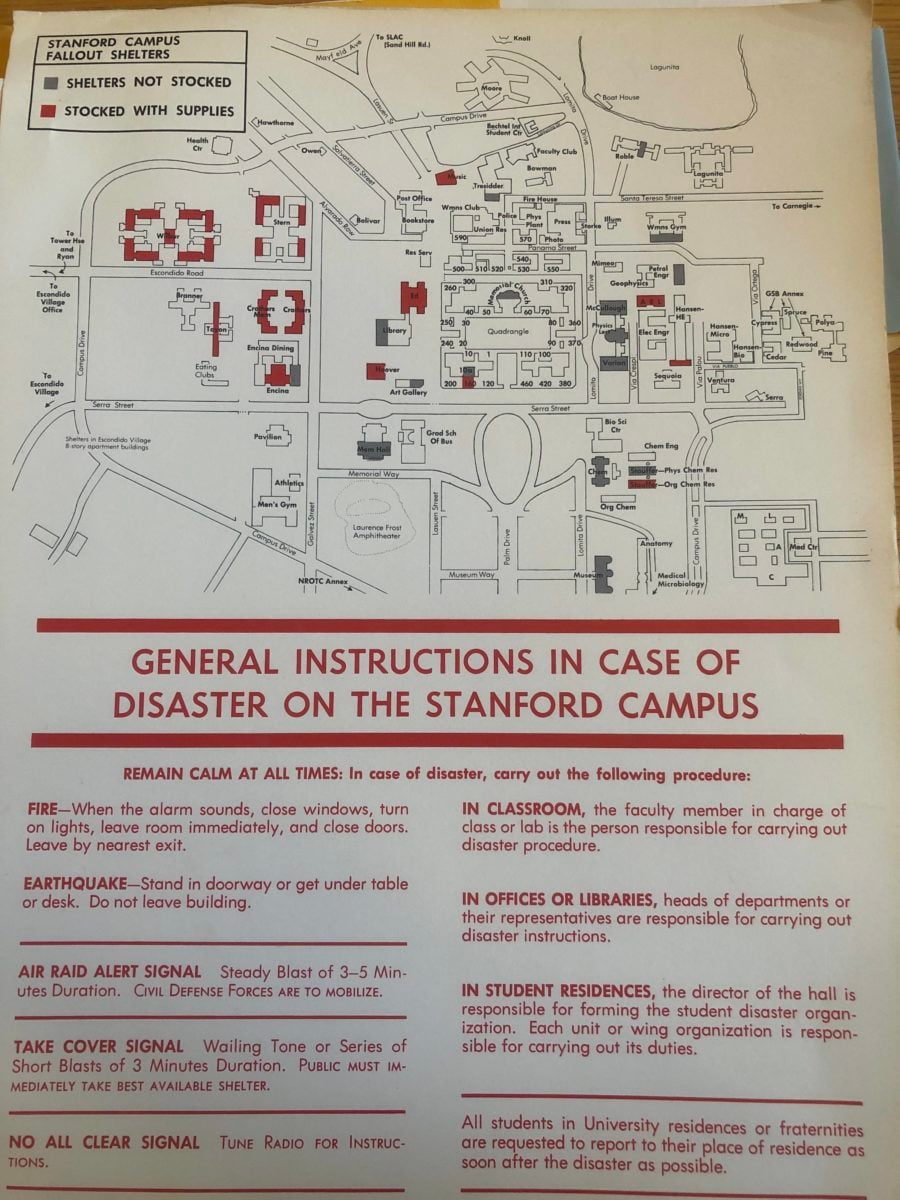

At the height of the Cold War, Stanford and the Office of Civil Defense, a federal agency established by Franklin D. Roosevelt, designated as many as 56 fallout shelters on campus. The University managed these shelters, which collectively had a maximum occupancy of 49,269 people, as a part of emergency plans in the event of a nuclear strike or natural disaster.

As time went on, student pushback, disagreement among faculty and the decay of supplies led to the gradual decommission of the shelters. Today, an abandoned fallout shelter off of Junipero Serra Boulevard — discovered only a few years ago when an undergraduate was found squatting in it — harkens back to a unique era of Stanford’s history featuring the University’s first formal protest and a 100-member student congress.

Shelters today

While some fallout shelters persisted through at least the early 1990s, no one really knows about them today.

“I cannot find anyone who knows about the presence of any shelters in residences,” Residential & Dining Enterprises spokesperson Jocelyn Breeland said in an email to The Daily. “My guess is that over the past 30 years anything that might have been considered a shelter has been repurposed out of existence.”

Keith Perry of the Office of Emergency Management (OEM) also confirmed that fallout shelters are no longer part of the University’s current emergency management program. Organized under Stanford Environmental Health & Safety, OEM is charged with creating a disaster-resilient campus and helping mitigate potential risks.

Although the shelters and their history have fallen off Stanford’s radar, University Archaeologist Laura Jones M.A. ’84 Ph.D. ’91 was aware of at least one remnant.

In 2013, Associate Director of Conservation Planning Alan Launer ’81 M.S. ’81 and a field crew noticed an out-of-place extension cord running through the dry grass near the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS), an interdisciplinary research lab in the hills between the Dish and Stanford Golf Course. Launer’s team watches out for conservation concerns at Stanford, and those foothills house the endangered California tiger salamander.

The cord was threaded through a pipe into a thick concrete structure submerged in yellow invasive grass and poison oak, a structure the team had walked around for two decades. The potential hazard pushed Launer and his team to open up the rusted hatch on top.

“We always thought it was a water tank,” recounted Launer, “until they opened it up and oh my God —”

Inside the seemingly humdrum structure was a hodgepodge of food and appliances: mason jars of mixed nuts, bedding and pillows, an oversupply of honey, fans, an electric massager, melted candles and more. A fifth-year undergraduate had been siphoning electricity from CASBS and living in the concrete structure — which appeared to be an old bomb shelter.

Launer called the University’s public safety department, and they came out and investigated. Launer said that they did not find any evidence of criminal activity, other than trespassing.

“As I recall, they put up notices stating that the bunker would be sealed off and that all personal belongings needed to be removed ASAP,” he said.

According to Launer, the student removed his stuff but was caught soon after trying to move back in. At that point, he was “talked to by either a dean or Public Safety.” An adviser was ultimately able to secure housing for the student.

(CLYDE JOHN/The Stanford Daily)

Launer took Jones, Provost Persis Drell — who grew up on campus in the 1960s — and me back to the site in July to see the shelter. The concrete bunker has since been welded shut and is checked by Launer’s team several times a year. Due to the small size, it is unlikely that the shelter was a part of the suite established for the public by the Office of Civil Defense in 1963.

Rather, the structure is more likely a personal fallout shelter — not unheard of for that time period. When it came to bomb bunkers, publications like “Popular Mechanics” sold booklets for as low as 25 cents with do-it-yourself guides and blueprints. “You Can Build a Low-Cost Shelter Quickly,” articles advertised.

Jones also reminded us that the Lathrop family, that of Jane Stanford, inhabited the land well into the 1940s and 1950s, suggesting the fallout shelter could have been theirs. In fact, the Lathrop house was just up the hill from the site. Regardless, the small shelter provides a window to Cold War-era Stanford — when fallout shelters took center stage.

‘Dark, cramped and dank’

The shelters at Stanford varied widely in size and location. The largest location, with a maximum capacity of 5,345 people, was housed underneath Hoover Tower. The smallest, which could carry a mere 51, resided in the basements of Wilbur Hall. In terms of structure, they ranged from repurposed basements to rooms constructed specifically as a shelter.

According to a National Fallout Shelter Survey (NFSS) printout in Special Collections, Stanford was not the only university in the Bay Area preparing for the worst. University of California, Berkeley, maintained 60 shelters, while Santa Clara University and San Jose State housed 12 and eight, respectively.

(Special Collections & University Archives)

Fallout shelters in residence halls were not uncommon, with records identifying shelters in the basements of Roble, Stern, Crothers and Toyon Halls. In 1989, Daily reporter Jeff Brock ’93 gained access to a neglected shelter under Casa Zapata. During this time, the University was no longer maintaining these facilities; while some shelters decayed behind locked doors, others were converted to storage.

“Inside the dark, cramped and dank room is an odd mixture of old and new. Like most former shelters on campus, it is sometimes used for storage,” Brock wrote in a 1989 Daily article. “Alongside Macintosh computer boxes and magazines dated ‘July 1986’ are fallout medical kits and 17-½ gallon canisters of water dated ‘July 1962.’”

In addition to these items, Brock found can openers, napkins, wire, toilet paper and commode lids. It was his narrative and journey into the shelters that initially piqued my interest in the story.

According to a 1968 memo from Ed Scoles M.B.A. ’57, who at the time was the assistant business manager of university residences, only about half of the licensed shelters were actually stocked with supplies at the height of the fallout shelter program. The most common food items stored in the shelters were biscuits and crackers.

Scoles’s memo also details that the Stanford Fire Department inspected stocks of supplies every 30 days, with periodic water testing. A shelter management course enrollment sheet reveals that a wide range of people managed these shelters, from firemen and police officers to food service employees and the treasurer to the City of Palo Alto.

Shelter management guides and sample schedules published by the University paint a clear picture of what day-to-day life inside the bunkers would be like. Mornings would begin at 7:00 a.m. with “lights on,” followed by the doling of daily rations and breakfast. Information sessions, evacuation trainings and fire drills filled most of the day, with free time, recreational activities and meals interspersed. Evenings ended with moderate quiet hours starting at 8:00 p.m. and “lights out” at 11:00 p.m.

“Those were the rough days,” former Civil Defense Coordinator John Marston recalled in 1989. “The directors of the dorms were very organized in case we had a red alert.”

But to more accurately describe the shelters and the controversy surrounding them, we must go back to their origins at Stanford — nothing a trip to Special Collections & University Archives can’t solve.

Beginning of the Shelters

Similar to the shock Launer’s team felt when its members opened the concrete slab in 2013, students returning to campus from their holiday vacations 50 years prior were met with a similar, ominous surprise.

According to Scoles’s memo, the shelter program at Stanford was launched during winter break, December 1962. Scoles wrote in 1968 that originally 27 shelters were marked with signs and stocked, while The Daily reported five years earlier that 18 shelter areas were established.

Scoles noted that some students objected to the program and described the fallout shelters as a brief “cause celebre.” Several letters in The Daily confirm this sentiment, including one penned by Peter Oppenheimer. The Daily was unable to confirm whether the author was, in fact, the same Peter as the son of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb.

In his book “Stanford in Turmoil,” former provost and president Richard Lyman explained that some critics of the Vietnam War believed that “by cooperating with the government in preparing for war, the university tacitly condoned the war policy.” He added, however, that some members of the Stanford community saw this connection as “far-fetched.”

Disagreement even consumed faculty, who argued over the merits of the shelters in a panel on civil defense at Stanford.

“Citing the horrors of Bamburg, Dr. [Leonard] Herzenberg asserted that the shelters on the Stanford Campus are far from adequate,” wrote Daily reporter Pell Fender ’66. “Dr. [Theodore] Roszak predicted that if further shelters were installed at Stanford, they may be considered to be provocative of nuclear war.”

On April 15, 1963 — a week after the group was formed to “host debates on off-campus issues, with the purpose of publishing statements” — the Stanford Student Congress voted 70-27 on a resolution to suggest the University refuse further federal funds for shelters, donate the remaining rations, remove all shelter signs and encourage research toward peaceful resolutions in conflicts abroad.

“The United States Government should discontinue the Federal fallout shelter program with the funds for civil defense to be turned over to an international agency such as World Health Organization, or UNESCO,” ended the congress’s resolution.

In a letter to the congress’s speaker, Nils Wessell ’64, then-President Wallace Sterling Ph.D. ’38 reminded students that policy concerning the shelters was the result of discussions with staff, the Committee of University Policy and the Board of Trustees.

“Should further Federal funds be offered us for expansions of the fall-out shelter program, we shall consider the issue on its merits, as indeed we did initially,” wrote Sterling. “We have no intention, however, of advising the United States Government as to how it should proceed in this matter. Nor do we intend to remove fall-out shelter signs from campus.”

Stanford’s first protests

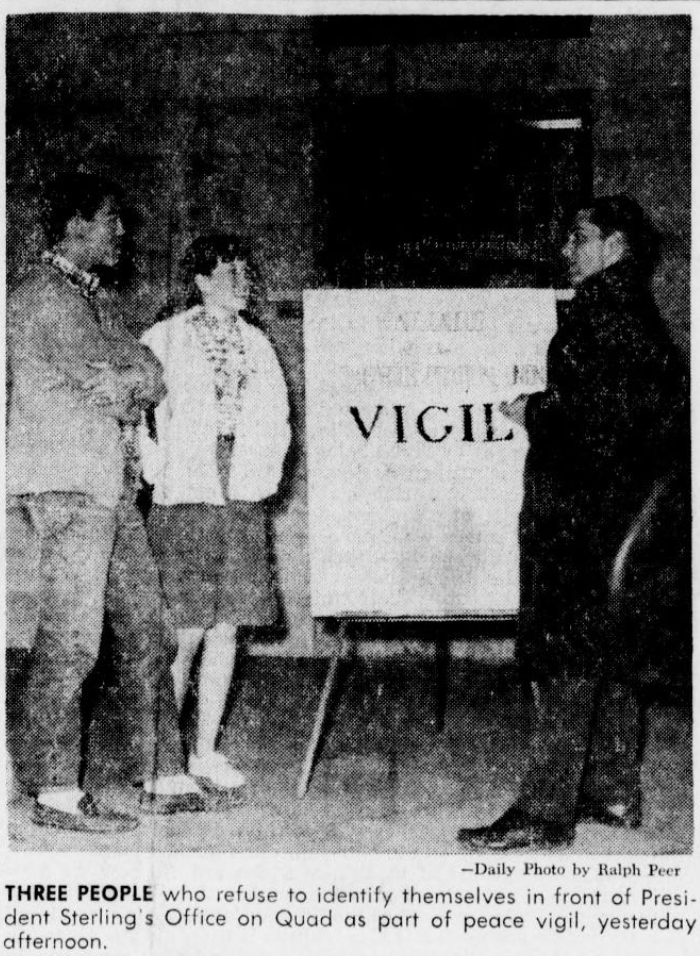

Earlier that month, a student group called the Peace Caucus requested to meet with Sterling and pushed for the abolishment of the shelters, writing to The Daily that “the presence of fallout shelters in our society enhances the probability of thermonuclear war.”

According to Lyman’s book, the administration’s refusal to meet with the caucus prompted calls from the Peace Caucus for a “permanent vigil” at Sterling’s office during the day and at his home during the evening. With no set policy or precedent for protests of this kind, Sterling soon declared that vigils must not interrupt the educational processes or business of the University and cannot take place in private residential areas.

(RALPH PEER/The Stanford Daily)

The vigil took place as planned, and Stanford security officers confiscated student body ID cards from protesters at Sterling’s home, which meant their case would go before the Judicial Council.

“Vigilists stated that they had no real hope of abolishing fallout shelters on campus,” wrote Daily reporter Bert Carp ’66 L.L.B. ’68. “But that they did hope to bring about a change in University policy regarding debate, and introduce the vigil as a new method of exerting the influence of student opinion.”

After threats of dismissal from the administration, the Peace Caucus ended the evening vigils outside Sterling’s home but persisted with protests during the day in Main Quad. According to Lyman, the demonstrators, satisfied with the administration’s willingness to reach a solution, concluded the entire vigil after about a week.

Two weeks after the vigil ended, a panel of administrators discussed the fallout shelter controversy in front of a “near-capacity crowd” at Cubberley Auditorium. The forum included Dean of Students H. Donald Winbigler, Vice President for Business Affairs Alf Brandin ’36, Director of University Relations Lyle M. Nelson and Director of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) Wolfgang Panofsky.

During the panel, Nelson confirmed that the granting of federal funds did indeed motivate the Trustees’ decisions to accept the fallout shelter program. Panofsky, a member of then-President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee, strongly expressed his opposition to the program.

“When asked if the shelters might give Americans a ‘false sense of security,’ Panofsky asserted ‘the program is so essentially ineffective that it leads to no false sense of security.’” Fender wrote.

Acknowledging the administration’s attempt to explain and listen, The Daily would describe the panel as a “significant turning point in the history of student-Administration relations at Stanford.” The immediate controversy over the fallout shelter program gradually petered out, but the spirit of the protests lived on. It would frame future demonstrations on campus, including a graduating senior’s anti-NATO protest at 1963 Commencement, the Stanford Committee for Peace in Vietnam’s sit-in at the lobby of Sterling’s office and the election of David Harris ’67 — who ran on the elimination of the Board of Trustees and fraternities, legalization of marijuana and an end to University cooperation with the Vietnam War — as 1966 Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) President.

The Fallout Shelter Committee

The shelter détente did not last very long, as the controversy resurfaced following a survey of Stanford’s shelters conducted by the U.S. Army in 1965. The inventory found that, while 27 shelters (accounting for a capacity of 11,703 people) were stocked with food and supplies, 29 shelters (accounting for 30,790 people) remained unstocked and unmarked.

Moreover, the shelters were the subject of vandalism. During the 1963 protests, exterior signs were torn down and never recovered, with Scoles estimating in his 1968 memo that only 10% of the signs remained in place.

Frank Holt, Santa Clara County’s Civil Defense Coordinator, formally recommended to Brandin in 1967 that federal funds be utilized to stock 10,000 more spaces by June 1968.

After Brandin failed to respond to his request, Holt followed up, prompting a staff meeting revisiting the fallout shelter program in April 1968. In his notes from the meeting, Sterling’s executive assistant Frederic Glover ’33, described the shelters as a “pesky problem” — referring to the controversy they caused just a few years prior.

The outcome of the meeting was the formation of the Fallout Shelter Committee, a group tasked with determining the future of the fallout shelter program. Originally, Sterling tapped Sidney Drell — the father of current provost Persis Drell — to lead the committee.

Over the course of his long career as a physicist at SLAC, Sidney Drell was a staunch opponent of nuclear proliferation and remained committed to arms control. A recipient of the National medal of Science from former President Barack Obama, he was also a founding member of the JASON — an independent group of scientists that advises the United States government — and cofounder of the Center for International Security and Arms Control (now the Center for International Security and Cooperation) — a think tank on international and domestic security issues under the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

“Most summers he was part of a group called JASON, so we spent most summers either at Woods Hole or, by then, La Jolla and we would just go there for six weeks in the summer,” Persis recounted. “He would also go to a bunch of conferences in Europe and we would all go with him.”

Like Persis said, this particular summer, Sidney Drell was out of the country, pushing Sterling to call on Panofsky — the SLAC director who was opposed to the construction of the shelters back in 1963.

Panofsky’s committee also included Scoles, Assistant Director of University Relations Don Carlson ’47, Dean of Students Joel Smith and Chair of the Chemical Engineering Department David Mason. On behalf of the student body, Editor-in-Chief of The Daily Dan Snell ’70, ASSU President Denis Hayes ’69 M.B.A. ’74 J.D. ’85 and activist Tim Buxton were also involved in discussions.

The inclusion of students in the committee was a point of concern for administrators. Glover advised Sterling that it would be best to “holdup action” on student involvement until after the ASSU election. The election pitted Hayes against incumbent Cesare Massarenti ’69, a frequent critic of Sterling who spurred public protest.

“If Hayes wins, we’ll deal with him as de facto president,” Glover wrote. “Joel thinks it would be madness to deal with Cesare on a nomination of this nature. So we know what we wish to recommend to you, but want to delay action until next week.”

Hayes ended up defeating Massarenti, and the Fallout Shelter Committee chose to incorporate student opinion into its decision-making process. On July 23, 1968, with Scoles dissenting, the committee recommended “that the University cancel its present Fallout Shelter agreement with the Office of Civil Defense unless this committee is convinced that the materials stored in the shelters at Stanford have an essential role in meeting natural disaster emergencies.”

What about earthquakes?

That same month, the Board of Trustees announced that Dean of the School of Medicine Robert Glaser would take over as acting president, as Sterling was set to retire. The transition caused the Fallout Shelter Committee’s recommendation to be nearly forgotten.

In October, however, Glaser sent a note to Brandin that he had “reason to believe that the students are apt to make an issue of the fact that the report had never been publicized.” The next week, Glaser notified the committee that he would be continuing the shelter program for natural disaster emergencies.

“I have asked that the present [shelters] be maintained as a potential resource in the case of a natural disaster such as an earthquake,” Glaser wrote. “Although it is unlikely, as your report pointed out, that help would not be forthcoming from surrounding areas, it seems to me that we may as well avail ourselves of whatever facilities are presently here.”

But Glaser quickly walked back on that decision after a meeting with Panofsky and the committee on October 18, in which the committee — excluding Scoles — expressed that they “felt strongly and unanimously that there was absolutely no point” in maintaining the shelters as a resource in the event of a natural disaster. As such, Glaser asked Brandin to notify Santa Clara County that Stanford would be disbanding the program.

In 1970, however, Kenneth Pitzer, the new University president, reversed Glaser’s previous decision upon reading a report titled “A Survey of Stanford Campus Vulnerability to Natural Disasters.” According to Pitzer, the report recommended “very definitely” that the supplies in the shelters would be valuable; they just were not “optically arranged” at the time.

Thus, Pitzer ordered that Stanford’s program would remain “in status quo” with Santa Clara County, meaning the shelters would remain on campus. Since then, the shelters have sat, decayed and, for the most part, faded from memory.

There are very few public records in Special Collections that date past 1970. Most of what is known comes from Brock’s 1989 article, in which he reported that many of the original spaces were being converted to storage.

Still, in 1989, “only the keys to the shelter below Casa Zapata could be located,” and there were over 50 shelters in the 1960s. There is a chance — however small — that behind some random locked door of an old residence hall or laboratory lies a “dark, cramped and dank” relic of the Cold War.

I, for one, am still on the hunt.

Special thanks to Provost Drell, Laura Jones, Alan Launer and Special Collections & University Archives. Aside from The Daily articles, much of the historical documents can be found in the Lyman Papers, Pitzer Papers and Office of the Dean of Student Affairs, Residence Division, Records.

Contact Patrick Monreal at pmonreal ‘at’ stanford.edu.