Each of the 2020 Oscar nominations for Best Live Action Short Film boldly centered themes of family, resilience, sorrow, comedy and, above all, humanity. None of the five films, hailing from Canada, France, Belgium, the United States and Guatemala, shy away from controversial issues, choosing instead to focus on complex portrayals of race, class and gender through the striking lenses of unexpected humor and tender empathy. “Une Soeur” and “Saria” both prominently feature the strength of women, while “Brotherhood” and “The Neighbors’ Window” explore familial issues in trying times; “Nefta Football Club” sits apart from the others, a witty portrait of two young boys’ (un)lucky discovery.

“Une Soeur” is the most suspenseful of the nominees, telling the story of a phone call between an emergency services correspondent and a woman who has been kidnapped. The woman, having lied to her kidnapper, must carry on her conversation as if she is speaking with her sister. Delphine Girard is masterful in her directing, cutting back and forth between shots of the woman in the car and the emergency operator, isolating the sixteen-minute film to those two locations. Further, the lighting of these two locations is starkly contrasted: the car is extremely dark and obscured; the audience is never even able to fully view the kidnapped woman’s face. There is no soundtrack or score — the only sounds outside of dialogue are the heavy, fearful breathing of the kidnapped woman and the sterile automated sounds of the emergency dispatch center. Through these stripped-down choices, Girard creates a film that is immersive above all else. Shaky camerawork, abrupt switches in setting, and an absence of identification of characters contribute to a palpable unease that grips audiences and raises heart rates. Focusing on two women attempting to deceive a man, Girard does not hesitate to touch on the societal harm of men’s violence against women — “Une Soeur” then serves as a testament to female empowerment in the face of danger, and the unspoken unity between women. The film ends with an unfortunately common resolution, one that leaves us relieved yet unsatisfied.

The only film of those nominated in this category based on a true story, “Saria” comes from notorious Super Bowl commercial-director Bryan Buckley. The story is centered around the 2017 Guatemala orphanage fire which occurred at the Virgen de la Asunción Safe Home in San José Pinula, Guatemala. A total of 41 girls between the ages of 14 and 17 years old were killed when a fire broke out. There have been no convictions of wrongdoing to date. The film’s cast is made up of children from Ministerios De Amor Orphanage, a fact which is revealed before the end credits, along with the names and ages of the 41 girls who lost their lives. We are told that “their cries for freedom will not be silenced.” In the film, the girls in the orphanage attempt to organize an escape, staging a riot to protest violence and unfair treatment and recruiting the neighboring boys’ orphanage to help them out. “Saria” is alive with adolescence: in the same conversation, the main character, Saria, and her sister, Ximena, talk about Ximena’s latest crush (a boy in the nearby orphanage) and hatch their plan to escape. “Saria” is perhaps one of the most cinematic films of the nominees. Inside the orphanage, the colors and lighting are hazy and muted, communicating the suffocation and isolation the young girls feel. When the girls look outside the orphanage, however, the film’s colors and lighting are brighter and fresher. Even though he varies his shots and images, Buckley finds his stride in representative poignancy: girls peer hopefully through broken windows, spiders survive the entire two-month span of the film, landscapes are shot widely and expansively. “Saria” highlights separation — youth and adults, freedom and captivity, justice and corruption; it asks us to experience the same fissures, forces us to listen, and allows us to see closer into lives that so often go unnoticed.

“Brotherhood,” the only other film in this category to be directed by a woman, is the turbulent, heavy, solemn story of a Tunisian family whose son has returned from battle, whose patriarch suspects him of working for the Islamic State of Iraq. The director herself, Meryam Joobeur, was raised in Tunisia and the United States, and the film is a co-production of companies from Canada, Tunisia, Qatar and Sweden. Accordingly, the film is a collage of moments, a collection of fragmented scenes, much like the action of memory and remembering. The quality of the video itself resembles that of an old video camera, furthering the concept of the film as a kind of home video; although, the film subverts that idea as we’re offered an inside look at a family previously torn apart, and only recently hastily stitched back together. Scenes are often cut off before we are fully satisfied, and they are laden with words unspoken and relationships we know nothing about. Joobeur’s characters are fiery, framed by sharp intersecting lines, asserting their presence on screen even in moments of restrained silence. Her dialogue wastes no time, and when her characters don’t speak, we are surrounded by natural sounds: the rustling of grass, wind through the trees, and textured rustic landscapes. Confined to their one-room home, the tension within the family quickly mounts, and leads us to a climax that is at once inevitable and heartbreaking. Spanning only one day, “Brotherhood” takes us on a jarring journey across warzones, through years of estrangement, and leaves us longing for forgiveness.

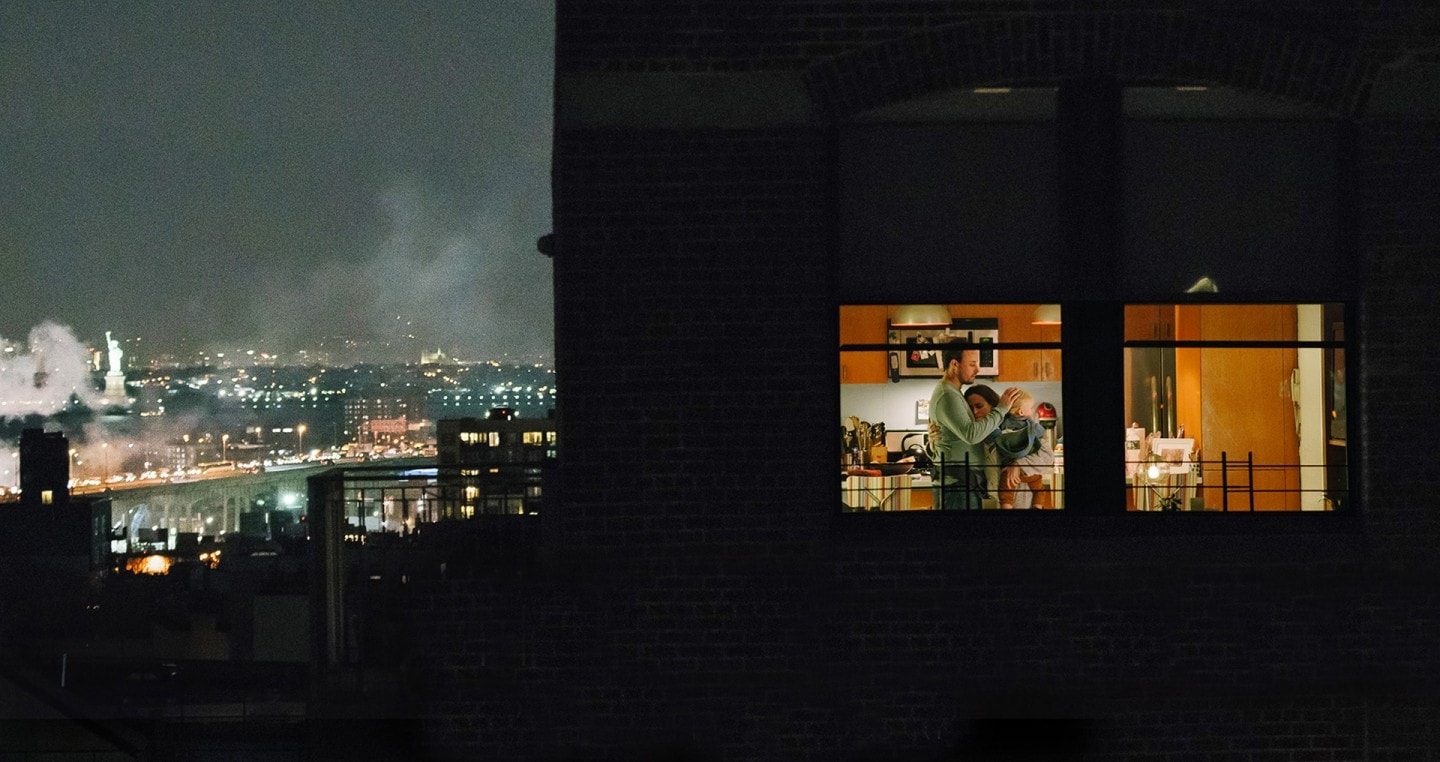

Marshall Curry’s “The Neighbors’ Window” presents us with the semi-mundane life of a middle-aged couple in their New York apartment, juggling raising two young children and a baby. Their lives are disrupted however, with the arrival of a hot young couple in the apartment building across from them, whom the middle-aged couple begins to spy on. Though they never spot anything as criminally dramatic as James Stewart in “Rear Window,” the couple becomes just as obsessive. Similarly to “Saria,” “The Neighbors’ Window” is naturally cinematic, featuring sincere, smart dialogue and placing the audience primarily in the lives of the middle-aged couple. We are afforded only a few moments of seeing the young couple — more often we only see the middle-aged couple’s reactions. The film takes us on an uncomfortable journey, isolating the characters to their respective apartments until the penultimate scene. Permeating the film is a quiet kind of sadness; we grow to realize the desperation of the middle-aged couple to experience youth again. Curry injects his unique brand of unassuming honesty into each scene, slowly but surely familiarizing us with the middle-aged couple’s obsession with watching their neighbors until we’re just as invested as they are. With the arrival of a heartbreaking climax, however, “The Neighbors’ Window” touches us as both a recognition of suffering and reconciliation with age. By removing the painful crux of the story one degree and placing it on the younger couple, Curry experiments with seeing and being seen. We become even further removed from the emotional core of the film, but we still sharply feel characters’ hesitations, and we ache for them to live more while they still have the time.

Perhaps the most energetic of the nominees this year is “Nefta Football Club,” a humorous adventure of two young brothers who stumble upon a donkey outside their Tunisian village. The younger brother is delighted, while the older brother quickly realizes the donkey has been wandering around the desert carrying a large amount of drugs. The director, Yves Piat, has created in “Nefta Football Club” an innocuously masculine film, both in subject matter and form. Starring only male actors, emphasizing the sport of soccer, featuring crass dialogue, “Nefta Football Club” is daring and sarcastic, interested in the present moment of the story and not much else in the way of a larger message or moral lesson. What follows after the boys discover the drugs is a winding course of mishaps, including a set of bumbling villains who pose no real threat. The brothers, Eltayef Dhaoui and Mohamed Ali Ayari, are delights on screen as they carry themselves with a dynamic, youthful ease that brightens the story and leads us to remember every mischievous young boy we’ve ever known. We are aligned with the older brother, Dhaoui, as we realize the stakes of the situation when the younger brother, Abdallah, disappears in the second half of the film. Ever-interested in finding the extraordinary in the ordinary, Piat displays his primary interest in light and sight. He places shots from overhead and shows only shadows, cuts off upper bodies and follows only legs running around a makeshift soccer field, and finishes the film with a wide rising shot that answers the most pressing question at the climax. “Nefta Football Club” has solidified its place as a salty-sweet delivery of wit and irony among the other nominees, and it reminds us of the joy of the unexpected.

In terms of predictions, “Saria” should win for its form, excellently executed, and for its content, heartbreakingly topical. Yet, “Brotherhood” will win, for it takes those aspects in which “Saria” succeeded and amplifies them in a way that the Academy will appreciate immensely. It tackles relevant social, political, and even economic issues across cultures and deepens their impact, examining their subtle yet detrimental effects on humanity.

Contact Marika Tron at mtron ‘at’ stanford.edu.