“Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world, yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history, yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.”

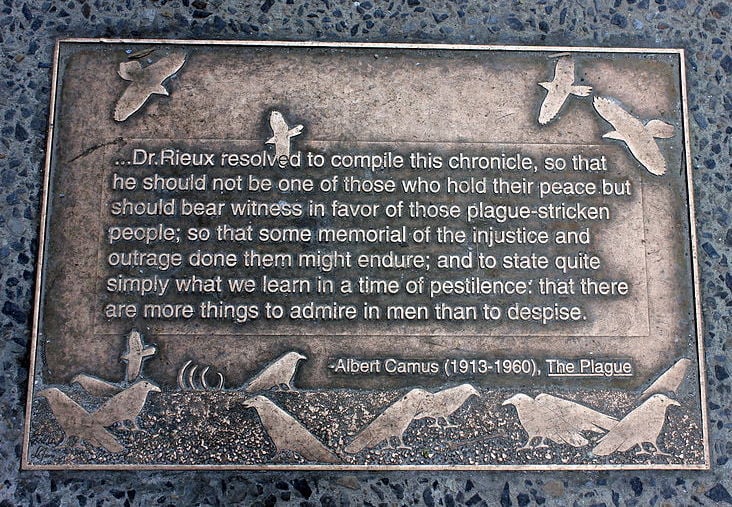

So muses Dr. Rieux, the protagonist of Albert Camus’ 1947 novel “The Plague,” which recounts a plague devastating the Algerian city of Oran in the 1940s. We, too, find ourselves living in a time of quarantine, disease, and general unrest. As I read Camus’ “The Plague” recently, the impact of COVID-19 appeared distant and intangible. But COVID-19 has taken the world by surprise and crept closer over the past few weeks. Today, COVID-19 appears pressing and indomitable. As I write this from my dorm room on Stanford’s campus on March 10, the number of confirmed cases worldwide of COVID-19 has reached 116,588, with 4,090 total deaths. The Stanford community itself has been personally touched, as a Stanford Medicine faculty member tested positive for COVID-19 and two students were possibly exposed to the virus.

The severity of the situation on campus and across the globe is undeniable. Yet, on our palm-tree laden campus of sunshine, speeding cyclists, and stressed students, COVID-19 is still often discussed as a matter of trivial concern with hints of xenophobia bubbling underneath the surface.

Across the bay, UC Berkeley recently found itself in a media frenzy after an infographic posted by its University Health Services listed xenophobia as a “normal” reaction to COVID-19. Although it may be true that infectious diseases often lead to stigmatization of the ill, it’s impossible to justify xenophobia ever being an appropriate response.

Disease need not lead to xenophobia or prejudice. In “The Plague,” Cottard, a black-marketeer who takes care of plague victims once the plague begins, tells his friend the priest, “The one way of making people hang together is to give ’em a spell of the plague.” In this paradoxical manner, illness, the harbinger of death, marks one of the few universal experiences of human life. We can, then, see the outbreak of COVID-19 through a lens of unification rather than ostracization. This distinction in no way attempts to romanticize illness or to find underlying meaning in intense emotional pain; rather, it only humbly remarks that the desolation of illness need not be compounded by the devastation of xenophobia. We can find solace in our efforts as members of the greater global community to limit the spread of COVID-19. As a growing number of hate crimes have been reported around the world since the outbreak started, we must be firm in our stance against prejudice. There is no place on our campus or in the world for xenophobia.

By avoiding the peril of xenophobia, we must also be wary of the danger of apathy and, beneath this, a deep-seated social trend of stigmatizing the elderly and the ill. Recent research indicates that the effect of COVID-19 on individuals is highly dependent on various health factors. It currently appears that the elderly, those with compromised immune systems, and those with pre-existing health conditions may be the most significantly affected. To the extent that Stanford students are young and healthy, we are significantly less likely to suffer from complications associated with COVID-19. Yet allowing this privileged status to turn our views of COVID-19 towards apathy is a grave mistake. The common rhetoric on campus that equates COVID-19 to a “panic” or expresses excitement at an “early spring break” fails to recognize the severe implications of the spread of COVID-19. Devastatingly, this rhetoric implies that the lives of the elderly or those with pre-existing health conditions are less meaningful and thus less deserving of concern. In this way, speaking dismissively of COVID-19 contributes to the systemic devaluation and dehumanization of the lives of those at greatest risk of suffering from the virus.

As we move forward, we must recognize that every separation of an individual from their family is an enormous strain, the experience of every individual who is stuck within their home due to fear of contracting COVID-19 is a tragedy, and the loss of each individual taken from this world by COVID-19 is a calamity of unspeakable significance. Let’s begin to discuss these events with the gravity that they deserve.

Perilously, the impact of this careless rhetoric extends further when it leads to careless actions. Those who consider COVID-19 a trivial concern are also likely to be those who will not take the proper precautions to hinder the spread of the disease. Despite the lower chance of developing complications from COVID-19, there is no evidence that young individuals are any less capable of spreading the virus. Given that many elderly individuals in the United States with pre-existing health conditions live in close proximity in nursing homes, this public health concern is of utmost importance. Hence, a collective public health effort is necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Even though you may not personally be at significant risk of experiencing complications from COVID-19, your neighbor, classmate or hall-mate may be.

We have reached a point where COVID-19 is the concern of all of us. Taking necessary precautions and treating the unfolding events with appropriate empathy and seriousness can help restore a sense of purpose and control that helps contain any sense of panic. Let’s recognize that our response begins with the rhetoric with which we discuss COVID-19 and ends with the distinct actions that we take to protect the larger community.

As each interaction carries increased significance, we must be cognizant of the manner and tone with which we discuss COVID-19, condemning xenophobic and heartless language while being careful to avoid rhetoric that trivializes the disease. We must also hold each other accountable in following fundamental CDC-informed guidelines including washing hands frequently and avoiding touching your eyes, nose and mouth. Finally, we must each make a concentrated effort to be non-judgmental and actively serve as up-standers who recognize and condemn xenophobia whenever it arises.

As many of us either head home for a period of indeterminate length or stay on campus for the foreseeable future, let’s seek solace in what Camus finds is the only bright side of an outbreak of disease: Ordinary people joining together can do immeasurable good.

Contact Ryan Crowley at rjc99 ‘at’ stanford.edu.