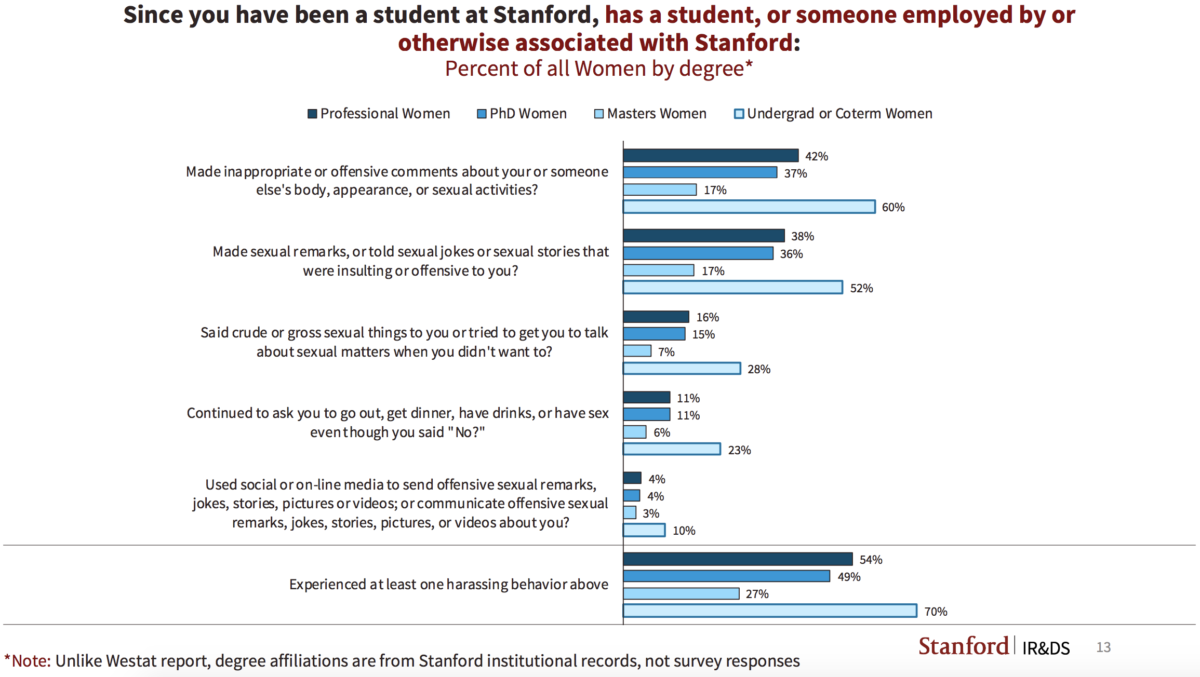

80% of transgender, gender queer or nonconforming (TGQN) undergraduate and coterm students and 70% of undergraduate and coterm women have experienced harassing behaviors since entering Stanford, according to results from a campus climate survey of students on sexual violence released last week.

Additionally, two thirds of Ph.D. TGQN students and nearly half of Ph.D. women said they had experienced harassing behaviors, which encompass verbal and virtual inappropriate or offensive remarks as well as physical touching.

The survey, which was organized by the Association of American Universities (AAU), highlights the continued prevalence of sexual assault and harassment on college campuses. While the aggregated data was first released last October, the new release disaggregates the data into categories based on community input, including separate categories for undergraduate and graduate TGQN students and specific data for students in Greek organizations and varsity athletic teams.

The survey was administered to Stanford students last April and May and was completed by around 62% of undergraduate, graduate and professional students.

The recently published data highlights the disproportionate victimization of female and TGQN undergraduate students and Ph.D. students at Stanford. Nearly a quarter of TGQN Ph.D. students experienced nonconsensual sexual contact by physical force or inability to consent since entering Stanford, a figure that is significantly higher than the 14.5% average for graduate and professional school students across the 33 schools surveyed by the AAU. The AAU survey most recently used by Stanford defines nonconsensual sexual contact in broader terms than Stanford’s 2015 campus climate survey in 2015. The new survey encompasses any breach of “affirmative consent” or ongoing voluntary consent.

“I am very disturbed by many of the findings in these survey data,” Provost Persis Drell told Stanford News. “We know that sexual assault and sexual harassment have been serious issues on our campus, and the new AAU data gives us a much clearer picture of how particular populations, such as TGQN students, graduate students and students in fraternities and sororities are affected.”

The results of the survey also indicate the magnitude of the impact that harassment has on students’ academic and personal lives.

55% of Ph.D. and 59% of undergraduate or coterm TGQN respondents said that harassing behaviors have interfered with their academic or professional performance, limited their ability to participate in academic programs or created an intimidating, hostile or offensive social, academic or work environment. Female-identifying respondents also indicated that sexual harassment has impacted their lives at Stanford, with 25% of women pursuing professional degrees, 32% of female Ph.D. candidates, 12% of master’s women and 37% of undergraduate or coterm women responding that they had experienced at least one such harassing behavior.

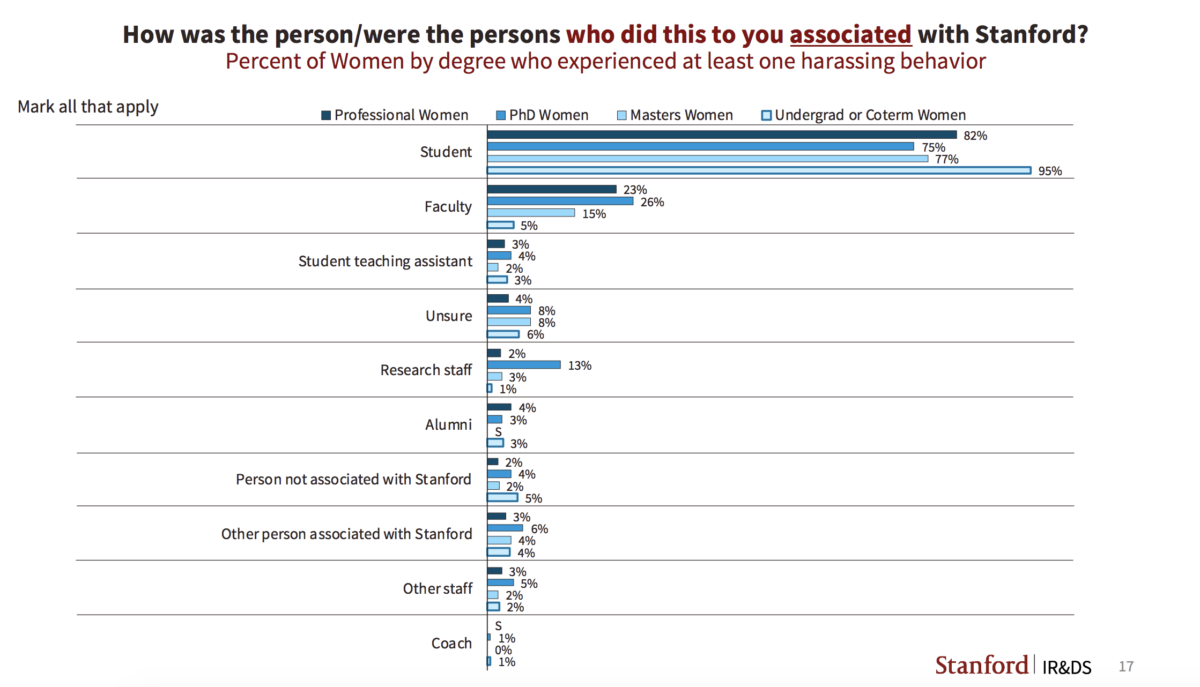

Most undergraduate students indicated that they were harassed by other students. Respondents pursuing graduate and professional degrees were generally more likely than undergraduate or co-term students to indicate harassment by faculty. 39% of TGQN Ph.D. respondents, 23% of professional women respondents, 26% of Ph.D. women and 15% of master’s women respondents indicated that they were harassed by faculty. 17% of men pursuing Ph.D. degrees also said that they had been harassed by faculty, in comparison to 3% of undergraduate or coterm men.

Fourth-year sociology Ph.D. student Emma Tsurkov, who serves as co-director of sexual violence prevention for the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU), said that Ph.D. students might be at a higher risk for faculty harassment because they typically spend many years at Stanford, and therefore are exposed to risk for a longer period of time than students in professional or other graduate schools. She also hypothesized that the disproportionate rates of faculty harassment for Ph.D. students reflect the fact that these students often work closely with professors.

“From my own experience, having been a student at a professional school at Stanford and now being a Ph.D. student, as well as the experiences of others, it is clear that Ph.D. students are particularly vulnerable to harassment by faculty,” Tsurkov wrote in an email to The Daily. “Ph.D students spend a lot of time, often one-on-one with faculty, giving harassers ample opportunity to prey on their victims.”

“Another reason for Ph.D. students’ increased vulnerability is the complete professional dependency on advisors when it comes to research, funding, and future employment,” Tsurkov added. “For most Ph.D. students, their advisor is one of the leading scholars in the academic sub-field they want to spend the rest of their professional life studying. Because there currently does not exist a good system of accountability for faculty perpetrators of sexual harassment, Ph.D. students often feel that there is no point in reporting.”

The survey results come at a time of heightened scrutiny and criticism over Stanford’s sexual violence and Title IX procedures and regulations.

When Stanford administered its Campus Climate Survey (CCS) in 2015, it was criticized for using overly narrow definitions and downplaying the prevalence of sexual violence on campus. The CCS found that only 1.9% of respondents reported being victims of sexual assault, in comparison with the 11.7% average reported in 2015 by the AAU survey that was used by many of Stanford’s peer institutions. In 2016, the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) passed a referendum to replace the CCS survey, and both the Undergraduate Senate and the Graduate Student Council (GSC) called for the switch to a new survey through resolutions in 2018, leading Drell to announce that Stanford would be switching to the AAU in 2019.

At an April open forum, faculty and staff spoke out against Stanford’s sexual assault and harassment services for having the effect of pushing out and silencing people who come forward about misconduct. Students also denounced Stanford’s resources, criticizing what they characterized as an inadequate response to reports of faculty harassment and a slow rate of policy change on campus. In May, the University revised Stanford’s Sexual Harassment Policy Office website after critics said that the page engaged in victim blaming and minimizing sexual violence, but criticism persisted.

Most recently, several female School of Medicine faculty members dicsussed with The Daily their experiences with sexual harassment and sexism, critiquing the University’s repsonse to allegations of misconduct and bias.

University resources

The results of the AAU survey also indicate low reporting rates and a lack of trust in University resources.

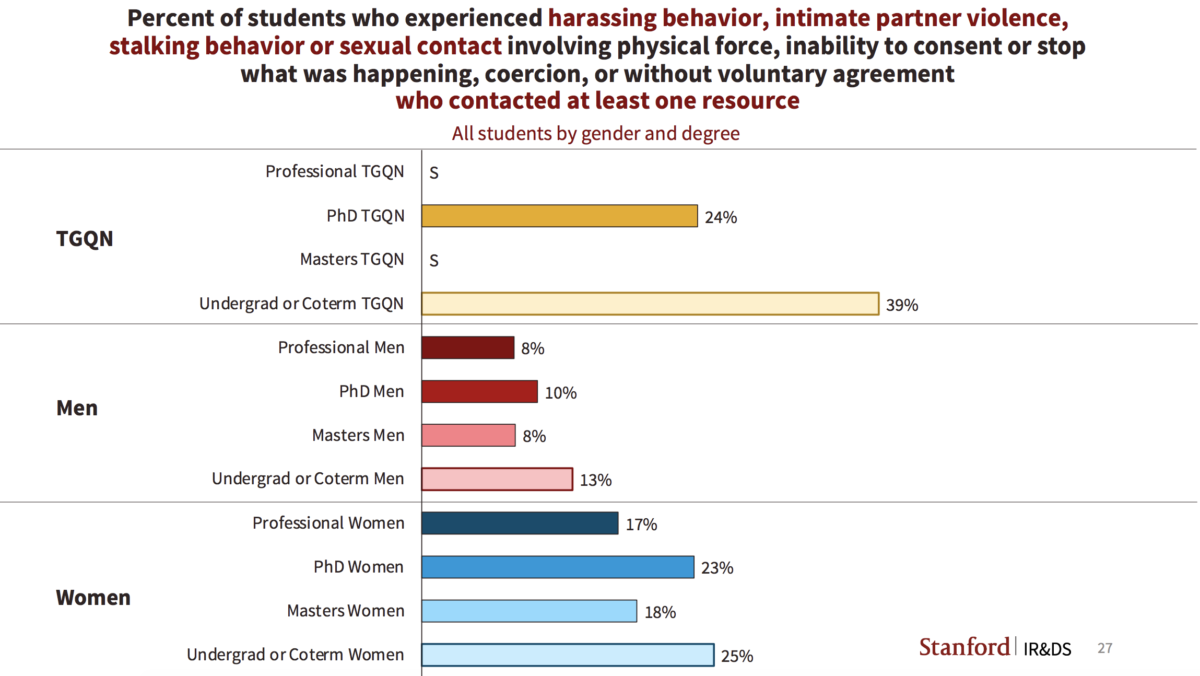

Men were less likely to seek sexual violence resources than women and TGQN students. Only 8% of male respondents pursuing professional and masters degrees, who experienced harassing behavior, intimate partner violence, stalking behavior or sexual contact involving physical force, coercion, inability to consent or stop or without voluntary agreement, contacted at least one resource. This number rose to 10% for Ph.D. males and 13% for undergraduate or coterm males.

In comparison, 24% of Ph.D. and 39% of undergraduate TGQN respondents contacted at least one resource, as did 23% of Ph.D. women and 25% of undergraduate women.

Respondents were generally most likely to contact Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) at Vaden Health Center after experiencing sexual violence, with 47% to 69% of respondents from each category indicating that they sought support through CAPS.

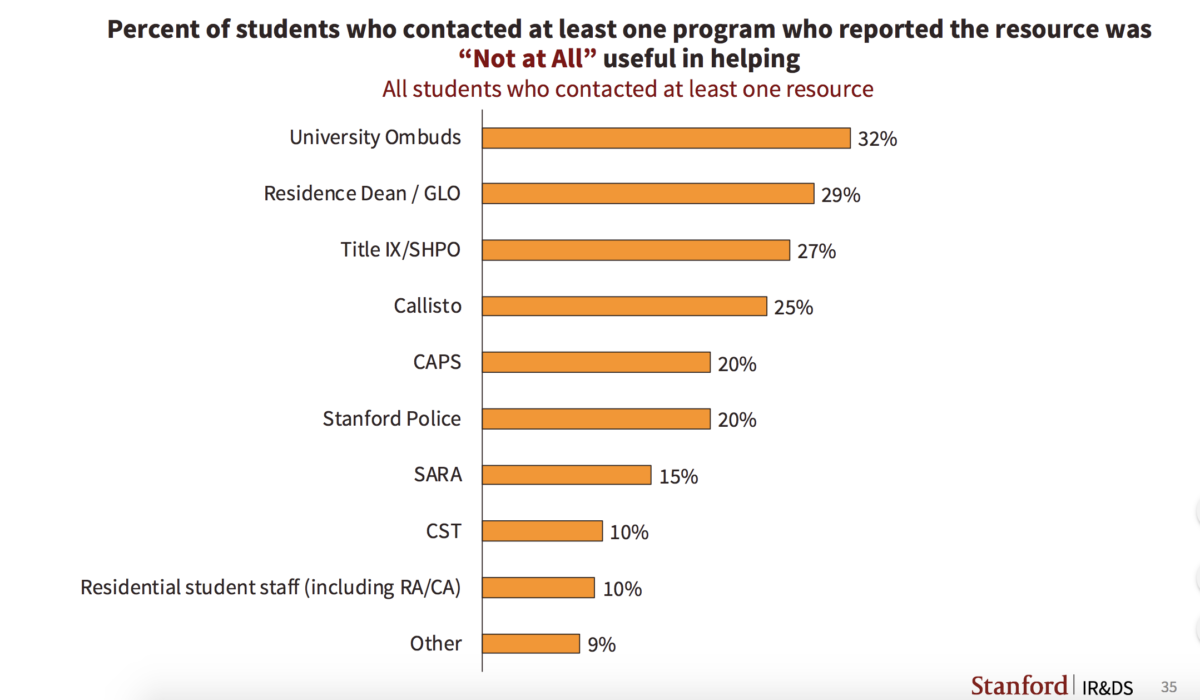

Some students who did seek out University resources said that their experiences with these resources did not help them. 32% of respondents who contacted at least one program indicated that the University Ombuds was “not at all” helpful, likewise with 27% of respondents and the Title IX Office/Sexual Harassment Policy Office and 20% of respondents and Stanford Police, for example.

“The survey data demonstrate that we need to make sure our entire community is educated about sexual harassment and sexual violence as forms of asserting power and as tools of oppression, and that such acts have no place in our academic community,” Vice Provost for Institutional Equity and Access Lauren Schoenthaler wrote in an email to The Daily.

Schoenthaler noted that in response to survey data, the University has been increasing upstander education to provide tools for witnesses to sexual harassment to intervene and has also been expanding smaller-group self-defense training. Recently, the University adopted a program known as “Flip the Script,” which seeks to empower women through verbal and physical self-defense and piloted a complementary research-founded corollary program for men called “Going Off Script.”

Fraternity and sorority membership

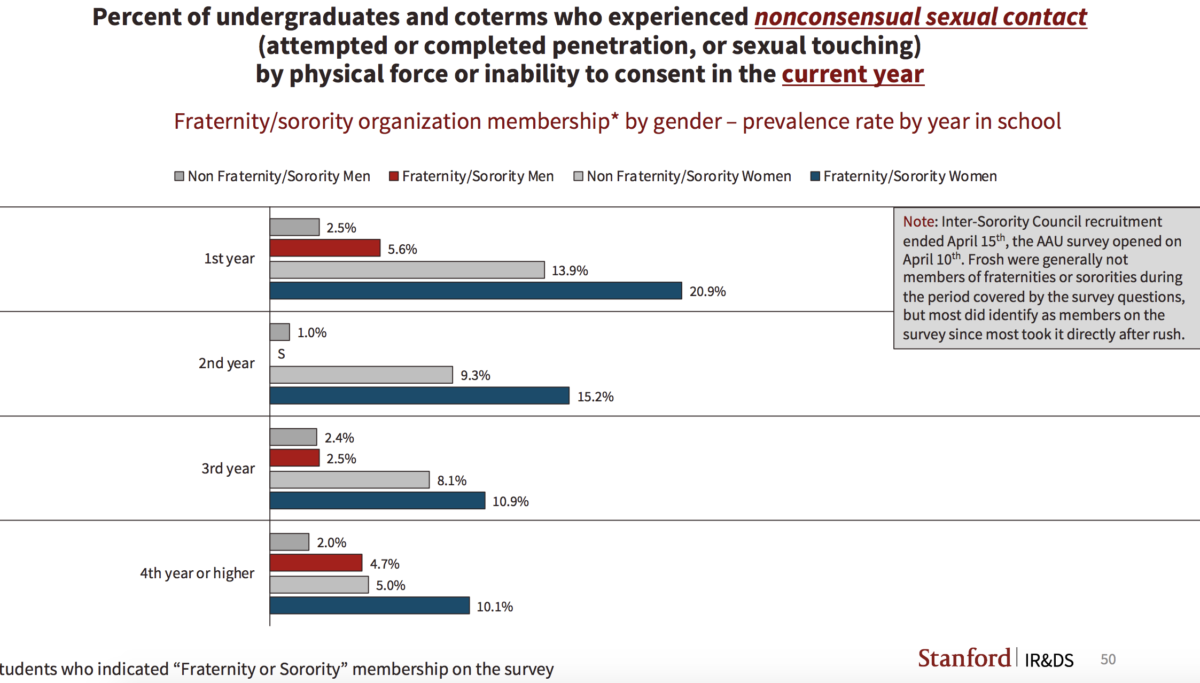

Students in Greek life were more likely to indicate having experienced sexual violence than non-members. Among undergraduates and coterms, sorority women experienced non-consensual penetration by physical force or inability to consent since entering Stanford at nearly double the rate of non-sorority women, 14.5% compared to 7.4%.

While Stanford frosh rush in the spring, meaning that frosh had just joined Greek life when they filled out the AAU survey, frosh women in Greek life were 7% more likely than their non-Greek peers to indicate having experiencing non-consensual sexual contact by physical force or inability to consent. Likewise, frosh men in fraternities were twice as likely to have experienced non-consensual sexual contact than frosh men who did not rush.

Students involved in Greek organizations were also more likely to indicate having noticed someone at Stanford making inappropriate sexual comments about someone else’s appearance, sharing unwanted sexual images, or otherwise acting in a sexual way that they believed was making others feel uncomfortable or offended. 51% of women in Greek life said they noticed such, compared with 40% of non-Greek women, and 40% of men in Greek life, compared with 30% of non-Greek men.

Bystander behavior

Undergraduates and coterm students were most likely to indicate having witnessed an incident that they believed could have led to an assault, with a fourth of undergraduate or coterm women and nearly a fifth of undergraduate or coterm men indicating that they had witnessed such a situation. While respondents from many categories responded at rates of around 50% or higher that they checked in with the party who seemed to be impacted, generally fewer indicated that they directly intervened in the situation or interrupted it or confronted the “the person engaging in the behavior.” Members of fraternities and sororities were more likely than their non-Greek peers to indicate that they directly intervened or interrupted, with 49% of women in Greek life and 26% of men in Greek life answering that they did such.

Many respondents said they encountered the perpetrator while socializing with friends or attending a party. Over half of undergraduate or coterm women who experienced unwanted sexual touching were in residence dorms when they encountered the perpetrator. Fraternity houses were the second most common location where some categories of respondents indicated they encountered the perpetrator, with 29% of undergraduate or coterm women who experienced unwanted penetration indicating they were at a fraternity house. 16% of women in Greek life who experienced penetration by physical force or inability to consent said that the assault happened at a fraternity house.

Next steps

In response to the survey data, the University has announced that it will seek to “effect change” in the areas of “education, culture and policy.”

The University’s next steps in addressing sexual assault and harassment will include implementing recommendations from external reviews, enacting changes to the Title IX process and evaluating offices that assist assault victims, according to Stanford News. The announcement also added that the University will draw upon recommendations from the newly formed Student Advisory Committee on Sexual Violence and Survivor Support, a joint effort between the Office of the Provost and the ASSU to give students a seat at the table in discussing Title IX regulations, procedures and resources.

“We are deeply concerned about the health and safety of our student community,” wrote Vice Provost for Student Affairs Susie Brubaker-Cole told Stanford News. “The data are sobering and represent an important call for us to change our campus culture to create a Stanford in which we can all thrive.”

Brubaker-Cole also said that more information about next steps will be available as the University makes decisions about the upcoming fall quarter.

“We have been speaking with colleagues at the University of Michigan to launch a program for TGQN students,” Schoenthaler wrote to The Daily. “We are working with them to ensure that the program for TGQN students is evidence-based and as effective as possible by assisting with recruitment for the research that is informing the program.”

Schoenthaler said that members of the Stanford community are encouraged to share their thoughts and ideas on how to address these issues using this form.

Students can contact the Title IX Office at [email protected] to report sexual harassment and sexual violence. Students in need of confidential support can reach out to the Confidential Support Team at 650-725-9955.

Contact Sarina Deb at sdeb7 ‘at’ stanford.edu.