Over the second half of 2020, I will be attempting to read one book a week from a list the Strategist curated by asking upcoming authors to recommend books they have turned to for solace during the present pandemic. Two weeks ago I reviewed “The Siege of Krishnapur,” last week I read Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feast” and this week I’m writing about Olivia Laing’s “The Lonely City.”

The San Francisco Chronicle described Laing’s work as “an uncommonly observant hybrid of memoir, history and cultural criticism.” There is no better way to capture the mesh of social science, art history, personal reflection and wonderment that constitutes Laing’s dissertation, which explores and characterizes the way loneliness in big cities has interacted with creative endeavors over the years.

First published in 2016, this work of creative nonfiction is primarily narrative in style but includes moments of first-person retrospection and supplements its analysis of artwork with quotes and, occasionally, photographs. Set primarily in New York City, this book spends most of its time discussing the lives and works of four artists: Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger and David Wojnarowicz. Each chapter dwells on the experience of loneliness in a specific light, ranging from common arguments linking loneliness to the rise of technology to fresh insight highlighting the unique role of speech and language in loneliness.

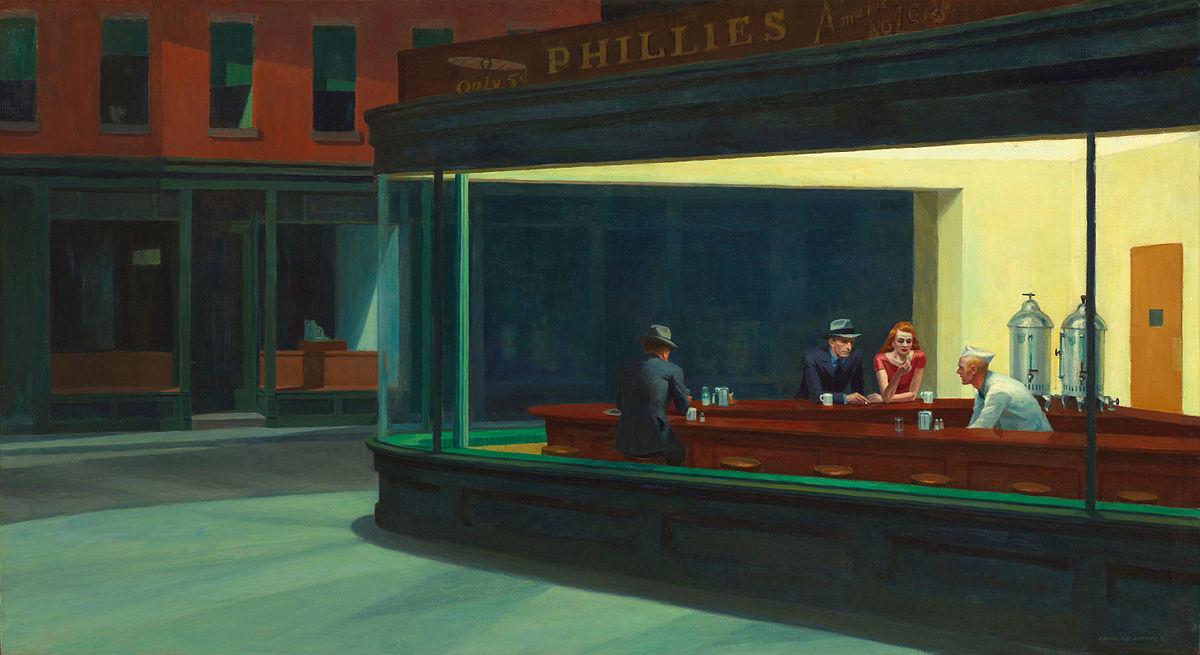

Chapter Two, “Walls of Glass,” examines Hopper’s visual depictions of loneliness. While analyzing one of his most well-known paintings, “Nighthawks” (pictured above), Laing talks about her experience viewing the piece in-person, writing, “A tour guide came in then, her dark hair piled on her head, a group of visitors trailing in her wake. She pointed to the painting, saying do you see, there isn’t a door? And they crowded round, making small noises of exclamation. She was right […] There was a cartoonish, ochre-coloured door at the back of the painting, leading perhaps into a grimy kitchen. But from the street, the room was sealed: an urban aquarium, a glass cell.”

She later wondered, in reference to the same painting, “Was the diner a refuge for the isolated, a place of succour, or did it serve to illustrate the disconnection that proliferates in cities?”

The experience of looking up the works of art Laing described and viewing them as I read Laing’s descriptions, of experiencing her book in a multimedia format, was extremely special. She not only provides insightful interpretations of the works she examines but also embraces a wondering, questioning tone. Much of Laing’s novel entertains open-ended questions without creating pressure for either her or her readers to find answers. Her ambiguity drew me in the way a slight undertow slowly tugs one’s feet towards the heart of the sea when standing in knee-deep water at the beach. It felt persistent, but kind; it created a space where I found myself thinking alongside Laing’s own take on the world.

The engaging nature of her book is further enhanced by the variety of media she explores in her discussions of art, discussing in Chapter Six, “At the beginning of the end of the world,” Klaus Nomi’s distinctive music and performance style and in Chapter Three, “My Heart Opens to Your Voice,” Andy Warhol’s tapes and films in the context of speech and its connection to loneliness. A discussion of Warhol is incomplete without mention of his attachment to machines as a way of coping with loneliness, and Laing deliberately notes this in a way that sets her up for referencing it later in the book, when in Chapter Seven, “Render Ghosts,” she fully dives into the ways technology interfaces in loneliness.

Laing’s ability to make her seemingly disparate stories intersect creates moments of unadulterated joy for the reader. We see chance encounters and long term collaborations and moments of connection that are surprisingly personal. In Chapter Three, after a long conversation around Valerie Solanas, a writer and radical feminist who attempted to murder Warhol after he refused to produce her work, she discovers that Solanas “found an apartment on East 3rd Street.”

“Later, I realized her building had backed directly on to mine, and that she too must have spent her days listening to the bells of the Most Holy Redeemer tolling off the hours,” Laing added. In a book that dwells for so long on as bleak a topic as loneliness, these moments where lives intersect and characters are serendipitously found to possess shared experiences are crucial. They act as moments of victory and redemption.

At moments like these, the physical setting of her work in New York City plays a valuable role in communicating a shared physicality between her diverse narratives. A recurring location that first comes up when she examines the role of deviant identities in loneliness (particularly queer identities) is the piers of New York, which were both a social epicenter and a safe haven for gay men in the years leading up to the AIDS crisis. She first romanticizes these areas and later uses the destruction of this romantic image to brutally convey the true impact of the AIDS epidemic. Localities like these serve to ground Laing’s writing and often provide occasion for her to transition between varying modes of narration.

Laing’s capability to seamlessly switch between her personal reflections and research-based writing forms a key element of her style. This is particularly evident in the chapter where she talks about the unique loneliness experienced by members of the LGBTQ+ community. At one point she discusses Wojnarowicz’s memoir, “Close to the Knives,” and writes, “He recalled how it had felt as a child to hear other children screaming [expletive] at one another, how ‘the sound of it resonated in my shoes, that instant solitude, that breathing glass wall no one else saw.’ Reading that sentence made me realise how much of his account reminded me viscerally of scenes from my own life; reminded me, in fact, of the precise sources of my isolation, my sense of difference. Alcoholism, homophobia, the suburbs, the Catholic church.”

This intermingling of reflection and research creates an intimate space where historical accounts no longer seem distant. Laing’s fearless interrogation of her own trauma encourages the reader to do the same. Reading this book took me back to times in middle school when I’d go days without talking to anyone in my class in more than half sentences. “The Lonely City” led to a lot of introspection and not just about my personal life.

I was forced to think about the collective life I inhabit as a citizen in 2020 — during a global pandemic — when her accounts of the AIDS epidemic were reminiscent of the COVID-19 crisis. Even her title for the relevant chapter, “At the beginning of the end of the world,” echoes how I often describe this year to my friends. At one point she quotes a protest banner that reads, “Died of AIDS due to government neglect,” another sentiment that rings all too clear in the context of both the novel coronavirus and the police brutality rampant in the United States. In this sense, her work creates a timeless journal that interrogates conflicts that will never stop being relevant: public versus private suffering, the pain of lying outside of your society’s version of ‘normal,’ protest, art, pain and ultimately loneliness.

I can’t help but think that her ability to create a reflective space for the reader is at least in part due to her endless capacity for empathy. She humanizes every creator she writes about, from murderers to photographers that some might characterize as voyeuristic. I didn’t really think of her humanizing as problematic because rather than concealing flaws, it seeks to understand their origins and to create a whole picture of how individual shortcomings are often products of systemic issues — homophobia, racism and income inequality, to name a few.

She is able to shift responsibility onto institutional origins in a rather insightful way and explicitly writes in the last few pages of her book, “Amidst the glossiness of late capitalism, we are fed the notion that all difficult feelings – depression, anxiety, loneliness, rage – are simply a consequence of unsettled chemistry, a problem to be fixed, rather than a response to structural injustice or, on the other hand, to the native texture of embodiment, of doing time […] in a rented body.”

In her last paragraphs, she offers a sort of guidance as to how one might conduct themselves in this kind of a world, where the ‘native texture of embodiment’ itself is often conducive to hate, pain and loneliness. She writes, “We are in this together, this accumulation of scars, this world of objectis, this physical and temporary heaven that so often takes on the countenance of hell. What matters is kindness; what matters is solidarity. What matters is staying alert, staying open, because if we know anything from what has gone before us, it is that the time for feeling will not last.”

I spent a lot of time thinking about what she might have meant when she wrote “the time for feeling will not last.” Does it refer to the way activism seems to be centered around especially significant moments in time that combine rage with the unshakeable need to create a better world? How might she view this kind of sporadic activism? Or, does she talk only about the individual and the way we must work to create bubbles free from loneliness for ourselves and those around us before time runs out? Maybe that last line is simply an ode to all the artists that have succumbed to the big scary forces of our deeply flawed, isolating world. I haven’t decided. Either way, this quote summarizes perfectly how this book as a whole feels deeply relevant in this time of protest, pandemic and pain. Laing ends on a tone of empathy and kindness that our world needs now more than ever.

“The Lonely City” drags you through the distresses of other times and places, yet inevitably romanticizes sadness and metropolitans and the passage of time in a way that makes you feel warm and fuzzy and wish you never had to leave the world this book created. I am guilty of having underlined long stretches of paragraphs (in pencil, I promise!), poignant prose I hope to come back to. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a ‘strongly recommend,’ and one of my favorite quotes from the book.

I love the following words because of how profoundly they apply to my own experience practicing escapism in the middle of a global pandemic through a reading list: “There are so many things that art can’t do. It can’t bring the dead back to life, it can’t mend arguments between friends, or cure AIDS, or halt the pace of climate change. All the same, it does have some extraordinary functions, some odd negotiating ability […] to create intimacy; it does have a way of healing wounds, and better yet, of making it apparent that not all wounds need healing and not all scars are ugly.”

Contact Smiti Mittal at smiti06 ‘at’ stanford.edu.