“Caught off garde” is a series of articles documenting the reactions of Stanford fencing, both past and present, to the July 8 announcement that Stanford Athletics would discontinue 11 varsity programs, including both men’s and women’s fencing, following the 2020-21 season. The first article in the series can be found here.

Stanford fencing is as old at the University itself.

First founded as a club in 1891, fencing was one of the most important sports worldwide at the time — popular enough to be one of just nine sports included in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896.

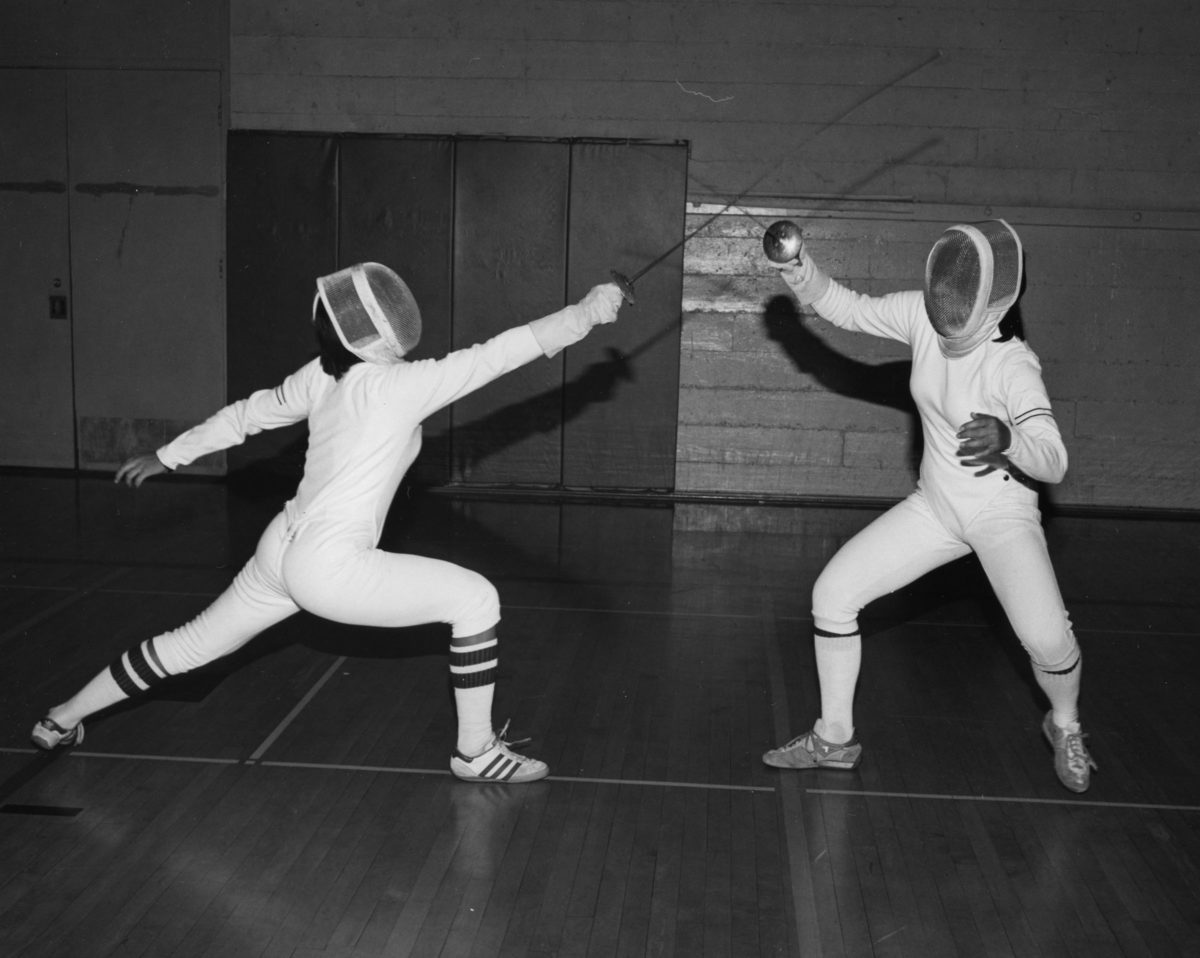

Fencing was promoted to an official “Minor Sport” at Stanford in 1916, and in 1941 the Cardinal took part in the first men’s NCAA fencing championships at Northwestern University. Women’s fencing became an NCAA sport in 1982, but women’s fencers had been part of Stanford’s program for more than 50 years at that point.

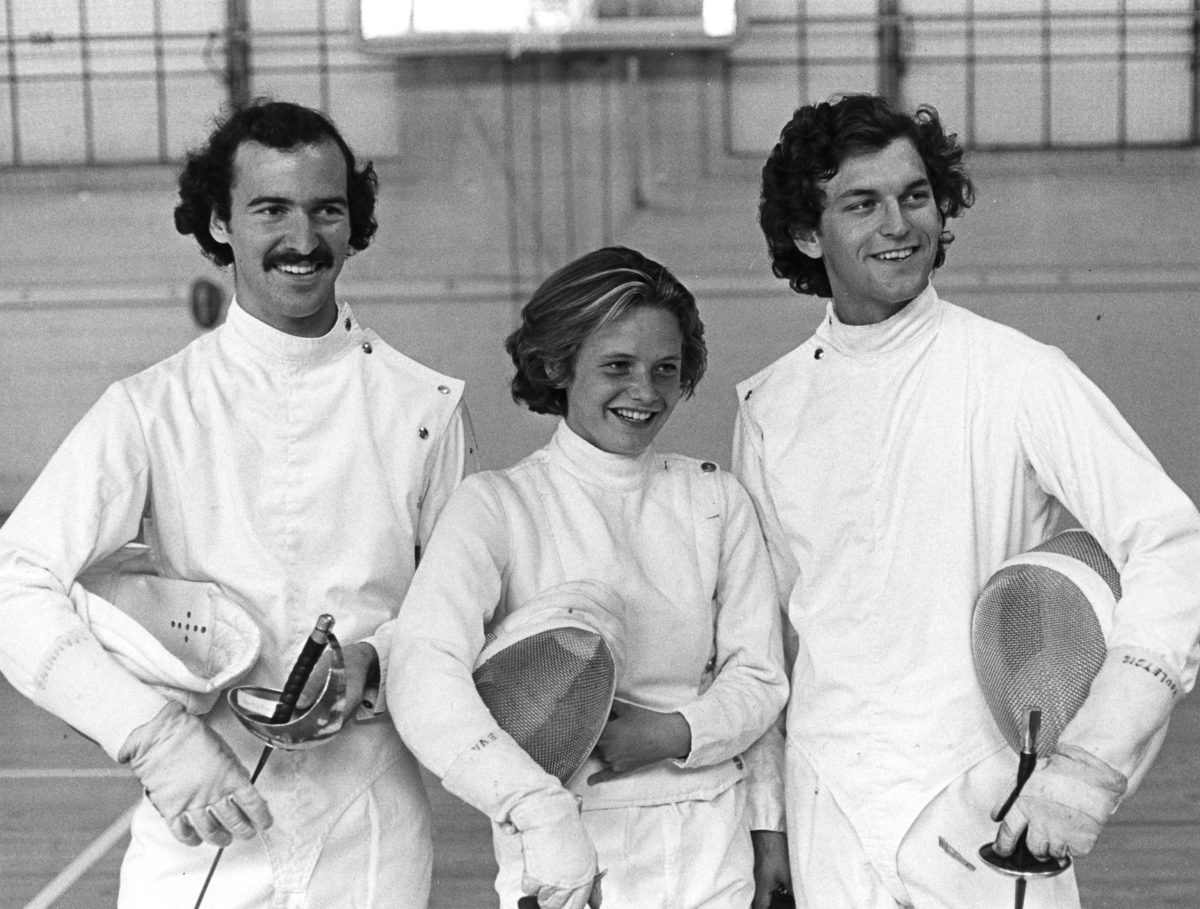

More recently, Stanford fencing has cemented itself as the “powerhouse of the West Coast,” as co-head coach Lisa Posthumus put it.

Co-head coach George Pogosov has been at Stanford alongside her for the past 18 years. The duo oversees both the men’s and women’s teams at Stanford.

Cardinal fencing is one of just four Division I fencing programs in the NCAA Western Region along with UCSD, Incarnate Word and U.S. Air Force Academy.

Posthumus, who took over as head coach in 1998, is Stanford’s third-longest tenured head coach, trailing just women’s basketball’s Tara VanDerveer (35 years with the Cardinal) and women’s water polo’s John Tanner (24).

During Posthumus’s time on The Farm (she was also an assistant coach from 1996-1998), the team has won the Western Regional Championships every year except for once in 2005. She has also led the men’s and women’s teams to consistent top-12 national finishes. Cardinal fencing also boasts nine national champions and six Olympians since its inception.

One such Olympian, foilist Alexander Massialas ’16, called his time at Stanford “unforgettable.”

“I’m really proud to have gone to Stanford,” he said. “I think anyone in the fencing world who knows me knows that I’m always boasting about my time at Stanford.”

Massialas, who competed at the 2012 and 2016 Olympic Games, was also the first Stanford athlete to clinch a berth at the 2020 Olympics prior to its postponement until 2021 due to COVID-19. During his four years as a Cardinal, Massialas was a two-time individual national champion (2013, 2015) and a four-time All-American.

Despite the international and collegiate honors, alumni and current athletes have made it abundantly clear that bonds made on the team extend well beyond the strip.

“My time on the fencing team was really formative. College is one of the most formative times of your life and Stanford in particular does a really good job of that,” Massialas said. “Stanford fencing was always a community I could identify with. I had friends on the team that I’m lifelong friends with now.”

Recently, the team began a tradition of senior send-offs, where fencing seniors would reflect on both their athletic career and broader Stanford experience with the team.

“You could hear each senior story about how this community has been so influential to their Stanford experience and how their love for fencing has blossomed,” said sabreist Carly Weber-Levine ’20. “Just seeing the way that fencing has touched each of these people’s lives just shows that this community is so important to so many people.”

Épéeist Sean Strong ’19 also recalls his own senior banquet, which he remembered as a memorable experience that strengthened his time as a part of the Cardinal fencing community.

“Each one of the graduating seniors got to give a talk about what the fencing team had meant to them, and I remember just that night realizing what an important part of my life it has been over the course of the past four years,” Strong said. “Just like any sport, [fencing has] taught me the importance of hard work, the importance of tenacity, the importance of teamwork, all of these core principles.”

Massialas, Weber-Levine and Strong are only a few of the dozens that Posthumus, the only woman currently coaching a men’s team at Stanford, has trained. She calls her time as a coach the “highlight of [her] adulthood.”

“What has stood out now at 50 years-old, and coming here as a 25-year-old,” she said, “is the ability to interact with these brilliant, free-thinking young student-athletes.”

But now, the end of Posthumus’s tenure at Stanford may have been expedited by the July 8 news that Stanford intends to cut the program in a year after 130 years of existence on campus.

“My first reaction was just shock,” Massialas said about hearing of the cancellation. “That shock very quickly turned into disappointment and frustration…This just feels like another slap in the face.”

Massialas quickly called Posthumus, whom he remains in contact with, to ask for her thoughts regarding the decision. However, she had only just learned of the impending cancellation herself.

Posthumus was informed of the University’s decision at a coaches’ meeting at 9:30 a.m. on July 8, just 15 minutes before her team found out through a Zoom call with athletes of all 11 discontinued varsity sports. The media and greater Stanford community received emails soon after.

“The entire day is like a fog,” Posthumus said, looking back on July 8.

Foiled finances

In its open letter, the University stated that athletics consistently faces multi-million dollar budget deficits due to offering 36 sports, which Stanford called “unsustainable.” In 2021, the deficit is expected to balloon to $21 million due to forced revenue loss from the COVID-19 pandemic, and cutting 11 sports would mitigate the deficit for future years.

However, how discontinuing the fencing program will significantly soften that major deficit remains unclear. Posthumus called the money fencing receives from the athletic department a “drop in the bucket” relative to other varsity sports, which cost the University significantly more.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Education, the operating game-day expenses for the women’s and men’s programs would be $32,865 and $28,308, respectively. The combined amount from these two varsity sports, $61,173, is smaller than all but one (synchronized swimming) single-team total.

This total, as Weber-Levine put it, is a “shoestring budget.”

Another factor limiting the budgetary strain of the fencing program is that Stanford does not provide athletic scholarships to athletes on either the men’s or women’s fencing team, despite the NCAA allowing schools the option of doing so.

“We only travel like three times a year,” Weber-Levine said. “We’re not a heavy hitter, like some of these other teams that have four or five full scholarships. We’ve never had that opportunity.”

While the ongoing pandemic definitely places “a lot of financial strain on any institution,” Strong said, the timing and vague reasoning of the announcement increased calls for transparency on the details of the decision-making process.

Alumni have also proposed solutions to the University’s financial burden. Given the lower costs relative to many of Stanford’s other varsity sports, for example, Weber-Levine and other alumni thought that donors and fundraising campaigns would seem like a realistic avenue to save the sport.

“I think that we would have been able to raise the money to support our team for several years,” Weber-Levine said. “We’ve been doing it for a long time; we can continue to do it.”

But the University FAQ page states that “the decisions to reduce our sports offerings are final, and any future philanthropic interest in these sports may be directed towards supporting them at the club level.”

With this door to maintaining varsity status seemingly closed, alumni are questioning why the University does not want to continue the conversation.

“We’re trying to understand that the administration did the best job they thought they could, in terms of trying to consider all possible sources of funding and whatnot,” Strong said. “I think looping in the actual people affected, the actual coaches and fencers and trying to work with them to find a solution is productive. Maybe at the end of that process, there is no solution. But I think that’s much better than just learning through a Zoom call that your sport has been canceled and you had no say or thoughts in that.”

The ramifications of this process will be felt most by current student-athletes.

As Massialas said, “they have to go back to school knowing they may not be able to compete ever again.”

When deciding on a college himself, Massialas, already a two-time Under-17 World Champion, hoped to remain near his hometown of San Francisco and his father, Greg Massialas, the coach of the USA fencing team. Stanford checked both boxes and also provided a top notch education.

“I made the decision to come to Stanford knowing that they didn’t have a lot of money in the program and [without a] full scholarship because I love the school so much and I wanted to be a part of the fencing program here,” Massialas said.

Due to this large gap between the cost of the fencing program and University budget deficits, the alumni community now asks for answers from the institution which once supported them.

“I’ll do whatever I can to help fight to keep these programs alive, whether that’s fundraising or awareness of what’s going on,” Massialas said.

Massialas, along with men’s rowing alum Nathalie Weiss ’16, recently published an open letter in response to the University’s decision. It currently has more than 5,000 signatures. An online, fencing-specific petition, separate from Massialas’ open letter, has gathered over 1,500 signatures.

“I would love to know where they came up with [the $21 million budget deficit],” Strong said. “I think it’s a bit of a black box, it’s a bit of a big number… What are the finances? What are potential ways you can keep these things afloat? What are potential ways that this might make sense for all parties looking forward?”

The pride of Stanford

In the open letter, the University cited the fact that there is only one other Division 1 fencing program on the West Coast as an additional reason to discontinue the Stanford program. However, many fencers took issue with this claim both because it runs against what they see as many of Stanford’s core values.

While it is true that the University of California, San Diego is the only other Division I fencing program in California, there are four total teams in the NCAA Western Region. Following Stanford’s discontinuation after the 2020-2021 academic year, the number of fencing programs in the NCAA Western Region will shrink to three, and UCSD will be the only collegiate NCAA program in the state.

“[Stanford’s] citing all the things about how only so many schools on the West Coast, or so many schools more broadly, have these sports,” Weber-Levine said, “and I found that really different from Stanford’s pride on being the only school to have something and how unique their institution is.”

Stanford’s breadth of athletics has been a major factor in its winning the Directors’ Cup, an award given annually to the school with the most overall athletic success, for the last 25 years. Without fencing and the other varsity programs, that streak may now be in jeopardy.

“For a school that emphasized persistence and flaunted school pride, it seems abrupt to just call it quits,” Weber-Levine said.

To the next generation of fencers, Strong had one piece of advice.

“Keep fencing,” he said. “Keep having fun. The announcement doesn’t change how awesome or amazing the sport is. It’s the best sport out of any of them in the world.”

For those currently fencing at Stanford, it is now a battle on two fronts: save the sport while competing to win in what could be its final year.

“We have one year left and a lot more uncertainty that we must face,” said a current fencer who was granted anonymity due to fear of repercussions. “If I could turn back the time, I would put an extra ten percent in at weights and morning practices in hope that my own school wouldn’t see a sport that I so deeply valued as a waste. Is there anything I can do? Unclear, but you best believe that all of us will be fighting till the end because we have a passion for this sport. And that’s what Stanford wanted anyways, right?”

Contact Jeremy Rubin at jjmrubin ‘at’ stanford.edu and Alysa Suleiman at 22alysas ‘at’ students.harker.org.