Editor’s note: With the hugely successful premieres of “Avatar: The Last Airbender” and its spinoff show “The Legend of Korra” on Netflix this summer, as well as as rumors of a Netflix-led, live-action “Avatar” project in the works, two fans of the original series revisit the TV-to-film adaptation of “The Last Airbender” (2010), directed by M. Night Shyamalan, which received poor ratings from critics and audiences alike. By critiquing the live-action version, these fans create a roadmap for future adapters of the beloved series.

Kelly:

After its release in 2005, the animated series “Avatar: The Last Airbender” was a major hit during its three-year run. With a simplistic yet powerful plot, “Avatar” managed to incorporate characteristics that went far beyond just a basic children’s cartoon. One of the main reasons “Avatar” remains so entertaining even 15 years after its release is because of its appeal to a wide audience. The show touches on themes such as authoritarianism, war and death, bringing in the more thought-provoking, real-world aspects for older teenagers and adults, while still incorporating the humor and excitement of its 12-year-old protagonist. “Avatar” did so well that a live-action movie adaptation, “The Last Airbender,” was released in 2010, directed by M. Night Shyamalan. Unfortunately, the live-action film was nothing like “Avatar” fans had been expecting, resulting in its whopping 5% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

After watching “The Last Airbender” once in 2010, I vowed to never watch it again. Given some recent rumblings that another live-action film remake is underway, however, I decided to rewatch the movie to analyze why it truly was such a disappointment for many “Avatar” fans. The list is lengthy, but if I had to sum it up, the majority of its flaws related to poor character development, incorrect story narration, bad pronunciation and — the biggest sin of all in my book — the “white-washing” of all key characters.

For those who are unfamiliar with the animated show, the story follows Aang, a young airbender around 12 years old. Siblings Sokka and Katara stumble upon the iceberg that Aang has been trapped in for the past 100 years before learning that he is the Avatar, a powerful being with the ability to control all four elements. Zuko, banished son of Fire Lord Ozai, is in charge of tracking down the Avatar to ensure his nation’s control over the world and regain his honor as prince. Each character has intrinsic characteristics and personal goals — both vital contributors to “Avatar” fans’ devotion to the growth of the characters. Aang’s appeal lies within his innate selflessness and fearlessness. Despite being the last of his kind, Aang is determined to master the four elements to defeat Fire Lord Ozai and restore world peace. Katara is known for her motherly love and kindness, but she also shares a concrete goal of mastering water-bending and helping Aang. Sokka is a strategic leader and also the comic-relief character, but he, too, has an objective of making his father proud while protecting his sister.

The live-action film characters simply could not hold a candle to the original ones of which we had grown so fond. Aang was portrayed as a somber, overly serious teen with absolutely no drive or heroic qualities. Aang’s complexity usually included his fear of letting people down, stemming from his past and the extinction of his people. In the film, however, Aang makes constant jokes about running away — showing none of the emotional depth and selflessness that make his character so interesting.

Sokka and Katara were also portrayed as static characters with no personal growth or development throughout the ill-fated film. The humor between the siblings fell completely flat, and Sokka was nothing more than a brooding teenager without the slightest sense of leadership. Even Zuko, one of the most driven characters in the animation, doesn’t convey the same desperation to restore his honor. The relationship between Zuko and his uncle Iroh is undoubtedly one of my favorite parts of the animated series — yet it was barely touched at all in the film.

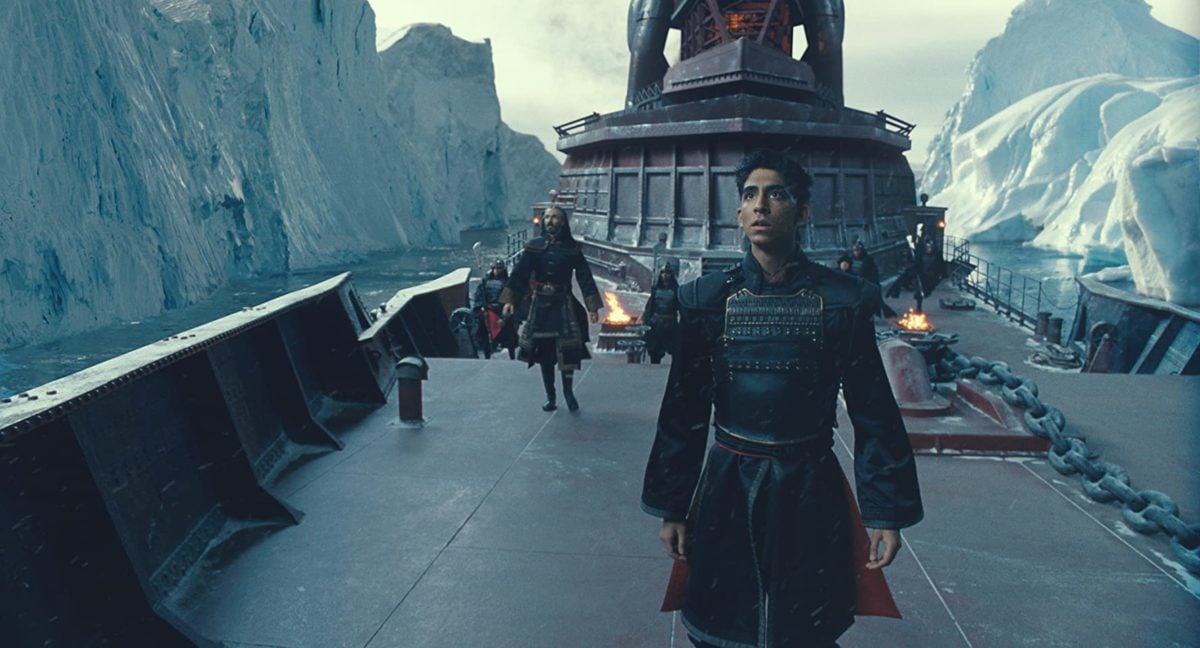

As if rebranding personalities weren’t enough, “The Last Airbender” also manages to get all the physical appearances of its characters wrong. The world of “Avatar” is influenced by Asian culture, where the Water Tribe, Earth Kingdom, Fire Nation and Air Nomas are based on Inuit, Chinese, Japanese and Tibetan cultures. Many Asian Americans were looking forward to the live-action film since Asian representation in media was rare in the early 2000s — so to see a predominantly white cast made them feel even more marginalized.

Moreover, Katara, Sokka and Aang are all played by white actors, while the antagonists were played by people of color, and still by actors of inaccurate ethnic backgrounds. If that weren’t bad enough, half the dialogue in the movie was pronounced incorrectly. While butchering names that were repeated almost hundreds of times in the animation is inexcusable, even the word “avatar” was even pronounced as “awh-vah-tar.” Additionally, Zuko’s scar — his source of insecurity and a symbol of his traumatic past — is barely visible on the actor’s face. The scar is a constant reminder of Zuko’s motivation to regain his honor and be welcomed back as the Fire Nation’s prince; since the scar is barely visible, the effect just wasn’t quite the same. Between ethnic erasure and the politics of casting white actors as the protagonists and people of color as the antagonists, the lack of cultural awareness and failures in casting only added more fuel to the fire.

Beyond the mutilation of character personalities in the film, the flow of the story was also incredibly difficult to follow. “Avatar: The Last Airbender” is a three-season show, but “The Last Airbender” film was meant to depict only the first season. One of the most challenging parts of movie adaptions is being able to consolidate the plot in under two hours, especially considering “Book One: Water” is a 20-episode season. Storytelling focuses on the right balance of action, dialogue and narration — any more or less leads to the possibility of confusion or boredom. In the animation, the protagonist’s backstory is slowly introduced along with world-building. But the film chose to narrate Aang’s backstory from Sokka’s and Katara’s grandmother, going completely against the storytelling philosophy of “showing not telling.” The uneven framework of “The Last Airbender” completely glossed over necessary context and vital plot points that would have allowed the audience to enjoy the flow of the story — instead dragging out uncomfortable and bulky dialogue scenes to make up for the film’s lack of narration.

Finally, a critical part of the show — which had the potential to be incredibly powerful — ended up being instead comical: element-bending. Ignoring the poor effects along with details that just didn’t make sense, the action scenes in the live-action just lacked the proper incorporation of bending. The characters in the animation manipulate their respective elements to further extend their fighting capabilities, but in the film it simply felt as though they were doing typical martial arts with an occasional addition of element bending. The bending in the film is so overdramatized by dancing and unnecessary movements, eliminating the balance of bending and fighting shown in the animation.

“The Last Airbender” movie was supposed to be the first of three films, but those plans were immediately canceled after this film’s poor ratings. At the start of 2020, there was hope for another live-action adaptation, but creators of the “Avatar” animation Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko recently announced they are no longer involved with the production due to creative differences — so the curse continues. Hopefully in the future, “Avatar” fans will finally receive a live-action movie that can live up to the same high standards portrayed in the animation.

Sania:

“Avatar: The Last Airbender” is a Nickelodeon cartoon show that aired between 2005 and 2008. It is three “books” (or seasons) long, and takes place in a world divided into four nations, one for each element: air, water, earth and fire. Each nation has people who are born with special abilities known as “bending,” through which they can bend their respective elements at will. Only the Avatar can master bending all four elements — the Avatar is a person who bridges the spiritual world and the physical, maintaining balance and peace in both. The most recent Avatar, however, a 12-year-old airbender named Aang, disappeared during a storm and was hidden in an iceberg deep in the ocean for 100 years. During that time, war broke out between the four nations, and the fire nation set its sights on world domination.

Amid the war, the Avatar returned and made friends with two water tribe siblings, waterbender Katara and her brother Sokka. The three are tasked with finding a way for Aang to learn how to bend the other three elements while evading the honor-driven Prince Zuko, the banished fire nation prince who is unable to return home until he captures the Avatar. The trio makes their way around the world in an adventure, facing many hardships and many joys. The storyline and their journey made “Avatar: The Last Airbender” one of the most beloved shows of all time.

One might expect that nothing could possibly defile such a masterpiece. If only that were true. “The Last Airbender,” a 2010 attempt at a film-adaptation of the show, was directed by M. Night Shyamalan, and garnered immeasurable dissatisfaction and hatred from fans of the original show. And there’s really no question as to why — those 104 minutes were torturous. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of where the film royally messed up:

10. How do you cram one season into a film shorter than two hours?

The only way to cram 20 episodes into a film shorter than two hours is to briefly mention, or skip altogether, many important aspects. Why even try, then, with a series as famed as “Avatar: The Last Airbender”? And more importantly, why condense it in the way “The Last Airbender” did? The flim glossed over important context given during the first season of the show that was meant to explain the plot, background and characters. The film skips numerous subplots from early in the show that not only become crucial later in the series, but are also important in showing the development of each character.

It makes me wonder how they planned to make a movie trilogy without including that contextual information. Examples include the Kyoshi warriors, the meeting between Aang and Roku in the fire temple, the group’s encounter with the Jet and his freedom fighters, the kingdom of Omashu and meeting King Boomi, Aang’s first attempt firebending and Katara’s journey to becoming a true waterbender. The film barely covered seven episodes of the 20-episode season, and even the episodes that were remade were not covered completely.

9. Random, illogical scenes that never happened were included

As if condensing 20 episodes to two hours isn’t ridiculous enough, extraneous scenes were also thrown on the overflowing plate. Many of these scenes didn’t exist in the show, and were also inconsistent with the logic in the show’s universe. When Aang is captured by Zuko for the first time in the film, he is taken aboard Zuko’s ship. It is worth mentioning that the way in which Aang was captured was senseless. In the show, it was made clear that neither Zuko, nor anyone else, had any idea what the Avatar looked like. The last thing they expected was that the Avatar was a child — after all, he had been missing for 100 years.

On the ship, Iroh performs a test on Aang, presenting Aang with a sample of the four elements and using them to expose Aang as the Avatar. This test never happened in the show — and even if it did, it would not have had the same result as in the movie because Aang did not know how to bend any element other than air at the time.

The film also indicated that Zuko thought Aang was the Avatar because of his tattoos. In the show, however, Zuko disregards Aang’s tattoos and suspects Aang because of his ability to airbend — something not shown until much later in the film.

Finally, in the film, Sokka, Katara and Aang decide to expose the Avatar to bring hope to villages captured by the fire nation. Katara is even seen hanging up posters with Aang’s face. This plot point is contradictory to the group’s intentions in the show: they hide Aang and expose his identity only when necessary, to effectively evade Zuko and the rest of the fire nation.

8. Poorly chosen directing style

Disregarding opinions about M. Night Shyamalan’s directing in general, the style he used just wasn’t suited for this task. He used static shots throughout the film, which contrasted the dynamic scenes and battles from the show. He also used cool colors throughout the film — the only exception being a depiction of Aang’s memories with the monks.

One of Shyamalan’s notable directing techniques is color symbolism. It was used in this film as well: the cool colors symbolized hopelessness in their world, while the warm colors in Aang’s memories portrayed his joy and nostalgia. But Shyamalan overlooked the show’s maintaining a proper balance of emotional and humorous scenes — it is, for the most part, a lighthearted show. The cool colors give the opposite effect, making the movie far too somber and foreboding. The unexpected use of awkward closeups throughout the film also make those scenes feel somewhat alarming.

7. Ignoring the “show, not tell” rule

An important part of storytelling is to “show, not tell” — but it feels as though Shyamalan went out of his way to violate this rule. The majority of the film is narration in the form of Katara’s voice talking over the video and in the dialogues. The dialogue in the film is used nearly exclusively for exposition, to the point where it feels that a summary of some parts of the show’s first season is told by different characters.

6. Bad acting

The blame for the disappointment in this movie cannot be placed on only the poor directing. Whether a product of being asked to play emotionally distant characters, poor acting skills or a combination of both, how the cast presented their respective characters was beyond disenchanting. The characters in the film lack personality, presented as bland, and there are no distinguishing features except for physical appearance. Their lines are delivered in monotony, offering no emotion.

To top it off, the film is filled with awkward facial expressions. It is bad enough that the characters are perceived as having emotional capacities of wooden boards — but whenever any emotion is shown, it is in a way that doesn’t match what is happening in the scene, forcing viewers to cringe, and further emphasizing the awkwardness and apathy of the film.

5. Disregard for the show’s tone

The apathetic, somber tone of the film, caused by both poor directing and acting, is contradictory to the warm, humorous and lighthearted tone of the show. “Avatar: The Last Airbender” is a comedic cartoon show, and while it does have its emotional parts, the show is mostly full of joy and laughter.

The film, however, is deadpan, lacking emotional and comedic scenes and characters. The worst offense is the film’s forgetting most of Sokka’s humorous character — he is a jokester. During the film, though, he does not tell any (intentional) jokes.

Aang is also fun-loving in the show, often found immersed in childish activities. In the film, Aang is shown as drab and serious.

4. Disappointing battle scenes

Considering the other shortcomings in the film, the least that could have been done was to include decent action scenes. Its battle scenes are some of the film’s cringiest parts. The characters make extraneous movements that produce anticlimactic and often worthless results. Additionally, the fighting sequences often appear more like aggressive dance choreographies than battle formations, leaving viewers confused as to what they are witnessing.

3. Disgraced the art of bending

One could argue that the reason behind the strange movements in the fight scenes is that the fighters are bending. Unfortunately, the excuse is invalid, given that in the show, each of the four types of bending reflects an existing martial arts form. Each bending form mirrors the element it bends: air bending is evasive, water bending is smooth, earth bending is defensive and fire bending is aggressive.

Each form of bending in the film was similar to the others. Additionally, in the show, the bending parallels the benders’ actions in real-time, whereas in the film the benders perform a series of useless karate moves (often making it seem as if they were fighting air) followed by a miniscule attack.

The most peculiar example of bending occurs in the earth prison: firebenders kept earthbenders captive in a prison surrounded by large rocks, which the earthbenders theoretically should have been able to move to escape. In the show, earthbenders can easily move large boulders by themselves. In the film, though, it took a group of six men to move one small rock, giving the impression that earthbenders are weak — they are, in fact, the opposite.

Another discrepancy was the interpretation that firebenders need an existing source of fire to bend — further emphasized toward the end of the movie when a group of firebenders were shocked that Iroh produced fire without a pre-existing source. The show makes it clear, however, that firebenders don’t need a source — part of what makes firebenders so unique.

2. Butchered pronunciations

Arguably the most irritating aspect of the film adaptation was the prevalence of mispronunciations. This blunder included the show’s main character, Aang, pronounced as “ay-ng”; in the film, he goes by “ah-ng.” This mispronunciation might be excusable if the show was adapted from a comic book, but it is based on a show where each character’s name is mentioned within the first 10 minutes and also repeated numerous times in each episode.

Other examples include Sokka, in the show pronounced “saw-ka” but in the film pronounced “soe-ka,” and Iroh, in the show pronounced “aye-roh” but in the film pronounced “ee-roh.” The most embarrassing mistake, however, is the mispronunciation of the word “Avatar” itself. These inaccuracies portrayed ignorance on the film creators’ parts while also making the film annoying to watch.

1. Racially incorrect cast

The most controversial aspect of the film adaptation is the racially incorrect cast. Much of the culture behind “Avatar: The Last Airbender” is derived from East Asia, and it is believed that the four different nations represent different ethnic groups from the region. Fans understandably expected an East Asian cast in the film — yet the main characters in the film were white, the protagonists were Indian and Iranian and the only East Asian characters were the earthbenders (who had fewer than 20 minutes of screen time). This all showed ignorance and disrespect toward one of the show’s most distinguishable features and its cultural background.

“The Last Airbender” was intended to be the first movie of a trilogy covering the entire “Avatar: The Last Airbender” series — but thankfully that endeavor was never pursued, likely due to widespread disappointment with the first attempt.

Netflix, however, is creating its own live-action TV show series for “Avatar: The Last Airbender.” What had previously provided some shred of hope for fans about this show is that the original creators of the show “Avatar: The Last Airbender” Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko were serving as the showrunners and executive producers. Unfortunately, some production issues caused DiMartino and Konietzko to leave the show, so fans of “Avatar: The Last Airbender” remain worried about what catastrophe we could witness next.

Contact Kelly Yang at kellyyang1 ‘at’ gmail.com and Sania Choudhary at choudharysania123 ‘at’ gmail.com.