Left behind: How COVID-19 impacted

Stanford’s FLI community

COVID-19 posed devastating challenges for Stanford’s student body, and among the worst affected were the

University’s first generation low-income (FLI) students. For many, Stanford’s shutdown in March began a

months-long ordeal as students struggled with the costs of a sudden move off-campus, unstable housing and family

situations and the emotional toll of living through a pandemic. The Daily spoke to members of the FLI community to

document their experiences, and ask whether the University was able to sufficiently support them.

Part 1: To stay or go

A pandemic begins, uncertainty reigns

As COVID-19 began to sweep the nation in early March, Stanford announced a remote spring quarter. Unlike some of its

peer institutions, Stanford assured students that campus housing would remain available. Many of Stanford’s

first-generation low-income (FLI) students breathed a sigh of relief. For some, leaving campus entailed a whirlwind

of financial demands and complex family situations. For others, home was simply not an option. In an otherwise

uncertain time, the university’s announcement promised some stability. Just three days later, however, on the

morning of March 13, an email from Vice Provost Susie Brubaker-Cole warned that plans were likely to change.

Vice Provost’s email

“Santa Clara County this morning issued an order announcing a new series of restrictions to

slow the spread of COVID-19. It is very likely that we will need to make changes to our existing plans for

undergraduates. We are giving careful consideration to these issues and will be in touch with you later today

with additional information.”

Brubaker-Cole’s email sparked hours of uncertainty among the FLI community. Some students felt Brubaker-Cole’s

email was cryptic, causing unnecessary panic.

Daniella Caluza

Class of 2021

CSRE and Symbolic Systems

Former co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“I remember the entire day being like, ‘I’m probably going to be kicked out, cool, cool,

cool.’”

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“That email made me particularly afraid because I felt like all of my stability was snatched

away.”

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I remember sitting across my friend at CAS (Center for African Studies) thinking like dude,

we can’t even study right now.”

On the evening of March 13, another email from President Marc Tessier-Lavigne announced that housing would no

longer be available to all those who chose to stay, but would be selective, prioritizing students with “no other

option than to be here.” Students, in the midst of finals, faced a choice between fighting for a spot on campus or

moving out with only days to prepare.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I literally couldn’t study at all that whole weekend. I had so many questions, like where

would I go and what about my safety and what about other international students who can’t just go home? I had no

idea what was gonna happen.”

Those who weren’t approved to stay were expected to leave campus by March 19 — just five days after the

announcement. Across campus, FLI students struggled with the uncertainty.

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“I’m not a FLI student who is homeless on paper, but I was well-aware of my parents inability

to take me in.”

Jess Dominick

Class of 2022

Engineering

Incoming co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“I just remember crying in Stern dining. Of course, there was some concern that they were

going to … kick us off. I was kind of like, ‘If they didn’t follow Harvard, then they wouldn’t do that, right?’

And then it was like, no, they would.”

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“Those few days of uncertainty were really traumatizing for me. I spent the days crying

almost non-stop, I wasn’t eating, I wouldn’t get out of bed, and it was the worst I’ve felt mentally and

physically in a really long time.”

Munira Alimire

Class of 2022

Anthropology and Urban Studies

Former ASSU Undergraduate Senate Chair

From Minnesota

“I just feel like it was really haphazard. I understand that, like, no one knew what the heck

was going on … but I would have preferred in some ways just to have known from the get go that Stanford wants

its students out by the 19th.”

Who Gets to Stay?

Munira Alimire

Class of 2022

Anthropology and Urban Studies

Former ASSU Undergraduate Senate Chair

From Minnesota

“Some students were told by other students, by RDs, by even ResEd staff themselves ‘Oh ok,

you don’t need to put in everything, because it’s just going to be like everyone’s welcome.'”

Jess Dominick

Class of 2022

Engineering

Incoming co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“Me and a lot of my friends when we filled out the form… put basic reasons… we didn’t go in

depth with all of our trauma [and] financial situations, because we didn’t know it was going to be used for

filtering us out based on our situation.”

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“As an RA, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to interpret that email. I

ultimately interpreted it as a form that helps students express why they need to stay on campus for the sake of

giving the university numbers, more so than it being a vetting process.”

Jess Dominick

Class of 2022

Engineering

Incoming co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“That was the initial impression. It was just a headcount.”

Caluza was denied on campus housing. Like many students who’d already begun packing for the five-day deadline, she

decided to forego the University’s petition process.

Daniella Caluza

Class of 2021

CSRE and Symbolic Systems

Former co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“I would’ve filled out that form a little differently if I knew this was going to be the

deciding factor for whether or not I had stable housing for the quarter. I filled out not like … shallowly but

not like getting into everything, you know?

That was one of the things that really irked me. I filled it out thinking it was more of a survey, like, we will

let anybody who fills this out stay, we just want to know why you’re staying for our own purposes … and then a

day or two after I had already submitted the form they were like, ‘Yeah, not all of you are going to be able to

stay by the way.”

Senior Jeff Rodriguez, who did not apply for on campus housing, headed back home to his family. He argued that the

University should have re-administered the form and called it a housing application.

Jeff Rodriguez

Class of 2020

Sociology

Former ASSU Director of FLI Community Outreach

From California

“There are people who filled out that form that weren’t able to really express their need…

Stanford should’ve just redone the form.”

After being initially denied housing on campus, junior Joel Johnson petitioned Stanford’s decision with a fuller

explanation of his circumstances.

Joel Johnson

Class of 2020

Sociology

Former ASSU Director of FLI Community Outreach

From California

“When I filled out the form the first time I was like, ‘Hey, I have home considerations that

make it unideal for me to go back home, even if I had to, or could,’ and they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re not eligible

— sorry.’

My dad’s got an immune deficiency disorder and I did not want to come home and risk exposing him to COVID, which

allegedly was already on campus … or risk accidentally killing my grandmother, who at the time was still

alive, and was being directly cared for by my mother.”

To his relief, Johnson was subsequently approved to remain on campus for the spring.

Joel Johnson

Class of 2020

Sociology

Former ASSU Director of FLI Community Outreach

From California

“They definitely didn’t do a very good job at explaining how much detail they needed.

Ultimately, just the way that Stanford went about selecting who could stay on campus I think was questionable.”

Tessier-Lavigne’s email said that Stanford would prioritize “international students who cannot go home; students

who have known severe health or safety risks; and students who are homeless” in deciding who would be allowed to

remain on campus. Some questioned if this fully recognized the FLI student community’s needs.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I think for international students, it made sense [to get priority], but at the same time,

it excluded a lot of domestic FLI students. I think they should have considered who actually needs to be on

campus not just like, ‘Oh, yeah, as long as you come from afar you can be on campus and if you’re a domestic

student just go home and figure it out.’”

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“I know FLI students who didn’t get approved to stay on campus, despite needing that space as

desperately as I did, if not more than me. I feel that I was only kept on campus because of my status as an RA,

so for my utility, more so than my need.”

Jess Dominick

Class of 2022

Engineering

Incoming co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“I know everyone likes to use the word ‘intersectional’ because it’s a great word, but being

FLI is truly intersectional. I wish the University understood that too, because even more class-privileged kids

can still come from backgrounds [and] households that are not good.”

Finding Home

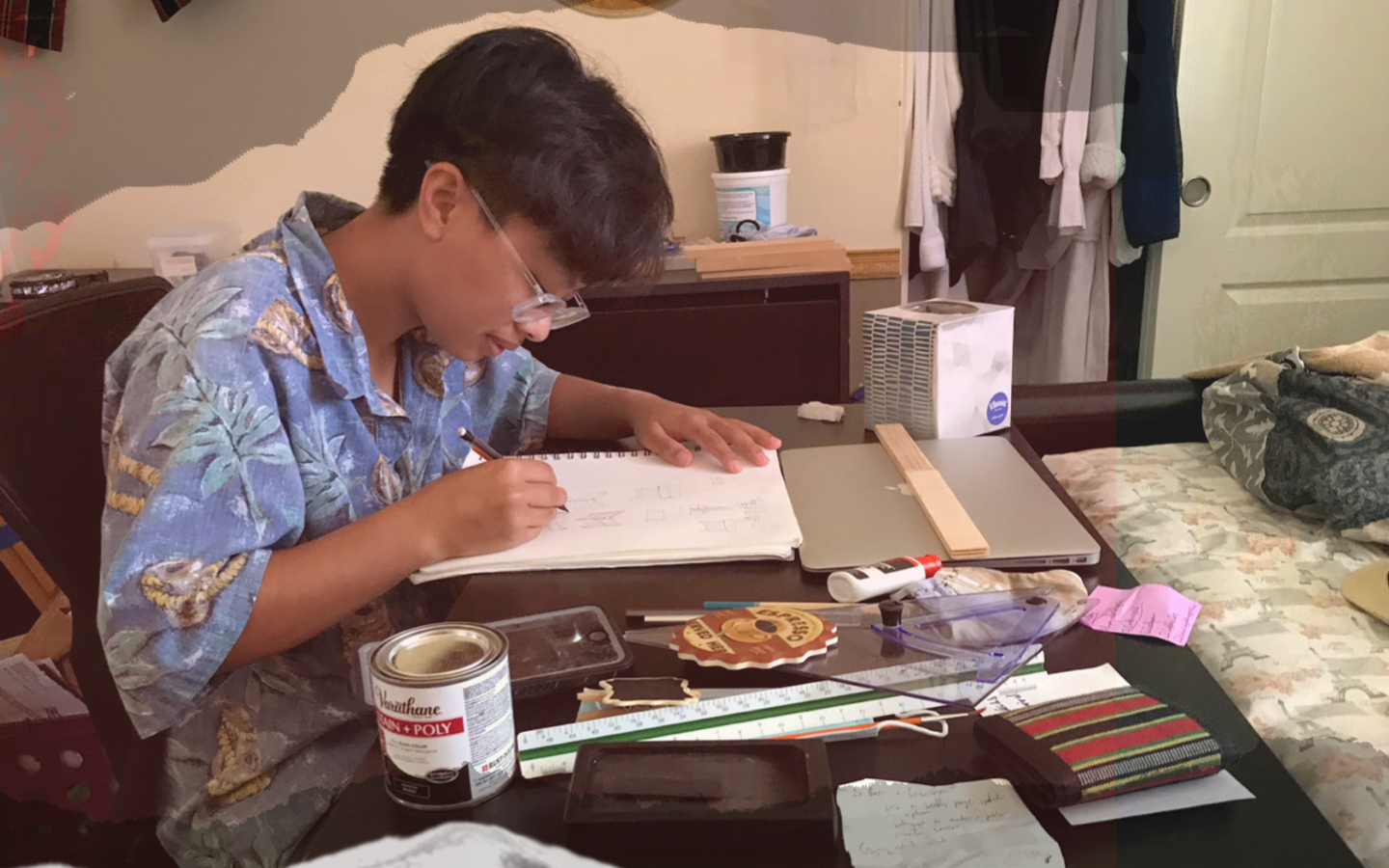

After leaving campus in a haste, FLI students struggled to find or maintain stability. While some settled into homes

with friends or family at the start of spring break, others weighed the financial and emotional tolls of these

options or even found themselves stranded. Even after finding a place to stay, stresses from the pandemic bundled

with concerns over academic progress, visa issues and finances — or friends who weren’t as fortunate.

Munira Alimire

Class of 2022

Anthropology and Urban Studies

Former ASSU Undergraduate Senate Chair

From Minnesota

“I live in a nice hospital town and I live in suburbia… I have a secure place to study. I

have a friend who has to study in the bathroom because that’s the only place that they can study… or friends who

do not have WiFi.”

Remote learning made the issue of internet access a national conversation, though it was already at the forefront

of many FLI students’ minds.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“Being FLI, I was worried about internet [and] money. I was like, am I going to find a place

where I can actually sit down and study?”

Alexess Sosa

Class of 2021

Human Biology

Former RA, Faisan

From Texas

“My area isn’t serviced by any of the WiFi carriers that the University was sending around,

so I was just thinking that there was no way I could go home and still be a student.

It was once again this reminder that rural FLI students are especially left behind.”

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I was accepted [to stay on campus] but again the pressure was like, ‘am I going to be the

only one on campus? All my friends are gone and I just had a rough winter quarter — how would my spring quarter

look like?”

Uwase, an international student from Rwanda, stayed with a Bay Area family so he’d have the space and internet

access to study. Sosa moved in with a friend in Southern California.

Amid unpredictable changes in federal immigration policy, FLI international students were left with many

unanswered questions regarding visas, pending summer internships and the ability to take online classes.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“If you leave the country, most organizations don’t allow you to work from abroad.”

Bibiche Keza

Class of 2021

International Relations

Public Relations Officer for Stanford African Students Association

From Kigali, Rwanda

“Like, okay, we do have the chance to go home. But if we do go home, how does this affect our

legal status in not just our academic endeavors but also professional ones?”

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I decided to stay here [in the United States] because I wanted to still maintain my

paychecks … and then also make sure I’m not in a position where if I’m trying to come back to the country and

borders are closed I’ll be stuck at home.”

International students on an F-1 visa can apply for Optional Practical Training or “OPT” — temporary employment

status tied to one’s area of study. Eligible students can apply to receive up to 12 months of OPT employment

authorization for jobs that provide practical training to complement their education. Eligible students can begin

using their OPT status time while in college, but that time is subtracted from the one-year maximum. Many

international students count on junior year internships to secure return offers for post-college work — making

this summer an especially critical time for international rising seniors.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I was lucky that I got a return offer from my last internship.

That chance to work for two or three years after graduation, to me, it’s even worth more than just being in

college for four years.”

Bibiche Keza

Class of 2021

International Relations

Public Relations Officer for Stanford African Students Association

From Kigali, Rwanda

“I talked to a friend last week, and he was supposed to be at Instagram New York and emailed

them and was like, ‘Oh, can I do remote working there this summer?’ They said yes and he went back to Ghana. But

then he realized he had to be in the States because they had to ship some of the equipment for his work to a

U.S. address, so now he’s trying to come back before June.”

Bibiche’s friend was unable to return on time to fulfill the internship.

Thierry Uwase

Class of 2021

Engineering

Student Leader at the Center for African Studies

From Kigali, Rwanda

“So the worst-case scenario is to end up going home because that would technically mean that

I’ll still lose visa privileges, which means I won’t apply for OPT, which means I won’t be able to work after

graduation… It would just be like losing half of my undergrad life.”

Even for students in the United States, panic began to set in as spring break trekked on.

Jess Dominick

Class of 2022

Engineering

Incoming co-president of the First Gen Low Income Partnership (FLIP)

From California

“There was a few days where I did not know, like, where I was gonna live.

We were looking at a bunch of different houses, me and a couple friends who also didn’t have places to go. Not

knowing where you’re gonna live, it’s scary.

I think having to move around three times, going up and down California multiple times trying to just live

somewhere showed me how much I value stability… how I didn’t realize Stanford offered that much to me until,

it was all taken away, you know?”

This is Part 1 of a series on COVID-19’s impact on the Stanford FLI community, continued here.

A previous version of this post misspelled the name of Daniella Caluza. A previous version of this post also inaccurately indicated this series had four parts; it has two. The Daily regrets these errors.

Contact Melissa Loupeda at mloupeda ‘at’ stanford.edu.