The Daily sat down with Laura Gamse, a current Stanford MFA student who recently received a Sundance Institute and Sandbox Fund grant for her film, “Brigidy Bram: The Kendal Hanna Story.” One of 10 2020 grantees, the award is meant to support the creation of films that combine nonfiction storytelling with science. Gramse has been working with her co-director Toby Lunn, as well as co-producers, Kareem Mortimer and Bernard Myburgh, in order to bring this film to life.

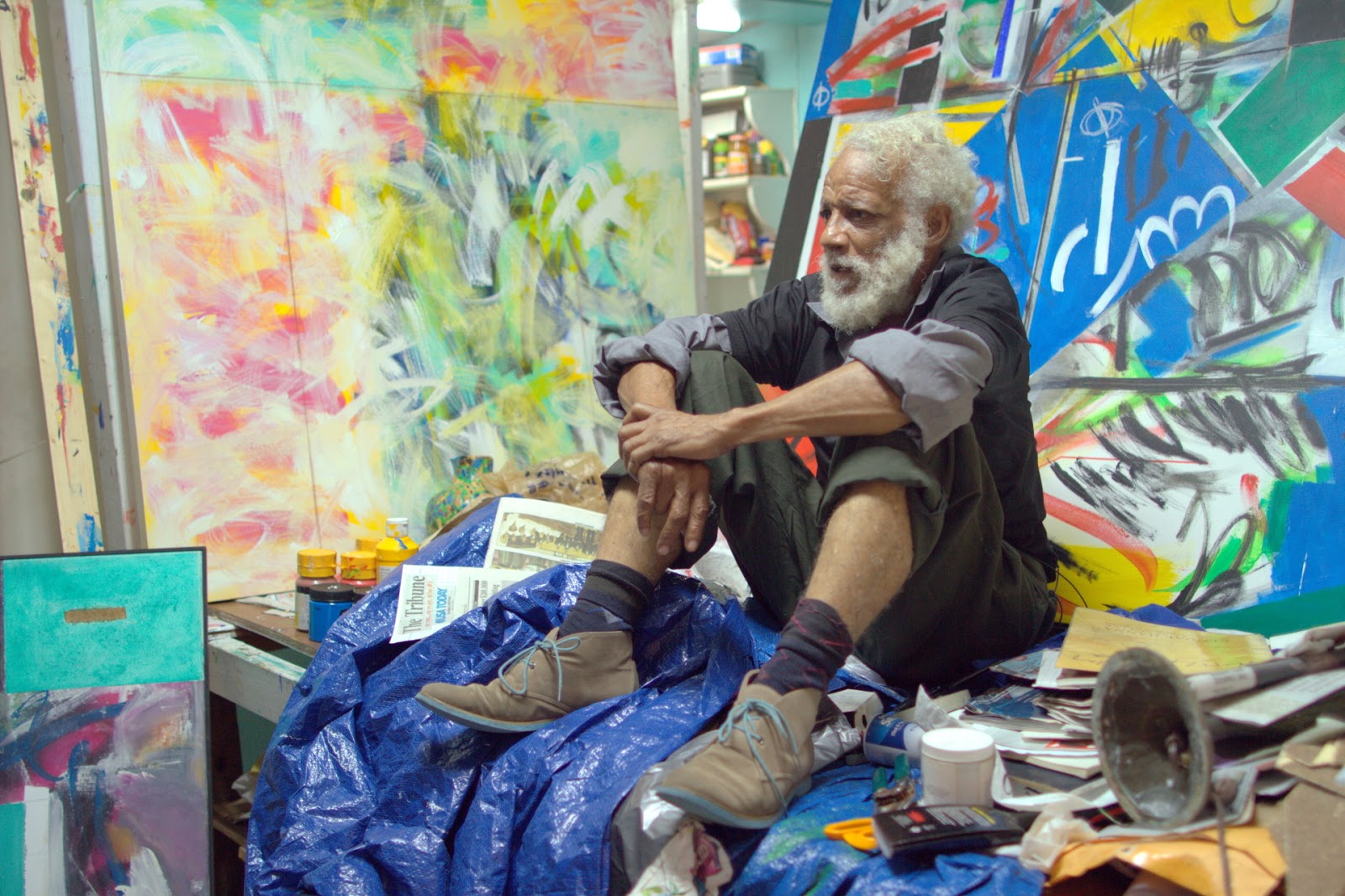

“Brigidy Bram: The Kendal Hanna Story” follows the life of Bahamian painter Kendal Hanna. In the 1950s, Hanna received a questionable schizophrenia diagnosis and was institutionalized. Years later, after his release, Hanna is living in an industrial building, sleeping on his paintings, when an art critic stumbles upon his work.

The Stanford Daily [TSD]: The “Brigidy Bram: The Kendal Hanna Story” project started around 2011. How have you stayed so committed to a project for so long?

Laura Gamse [LG]: We never thought it would be this long. We first made a short film, and we were planning to release that. But we got such a great reception, from the kind of private audiences to which we showed the short film and test screenings, that we realized we had what was needed to kickstart a feature film. And short films kind of get short shrift in the International Film Festival world, and think about how many short films you’ve seen in comparison to feature films; they just don’t get out there as much. So, since our goal was to make Kendal a household name as a great artist, we wanted to make a feature.

It’s a good thing we decided to [make a feature] because it turns out that his story is every bit as complicated as a feature film necessitates, and it provides interesting options for exploring what it means to go through a period in life in which society is gaslighting you. When everyone is telling you, “You’re crazy,” but you don’t feel that way. You don’t feel that you need to be institutionalized, but those around you are telling you that you need to be institutionalized for life.

TSD: How has the filmmaking team handled telling such an emotional story while being sensitive to your subject, Kendal?

LG: We worked with Kendal every step of the way as part of the creative process. Anytime I would finish editing a new scene, I would show it to Kendal and get his thoughts on it. And Kendal from the start has said, “You’re an artist too,” you know, he’s given me the license to take his story, or my understanding of his story, and with my co-director and producers create an artistic piece.

By no means is this the objective story of his life — it shouldn’t be seen as the one way of telling his story. This is just our way of telling his story. Even now when I’m in the U.S. and Kendal’s in the Bahamas, and we’re separated due to COVID, I’m calling him every week and making sure that we are on the same page. That’s a crucial part of this as well that I think differentiates between standard journalism and documentary film … With something like this, it’s really important for him to see everything and to be a part of that process.

TSD: In working on this project, how have you thought about this broader conversation in art of telling stories about those in disadvantaged situations in a way that best amplifies their voices, without taking up too much space yourself?

LG: The first question was, “Does Kendal even want us to make this film?” of course, and, you know, it was never a question of whether I would make this film alone. It was always a question of, “Will we make this film together?” Myself, my co-director, my co-producers, etc., and Kendal, of course, being kind of the central figure.

It was never a question of will we have a narrator. It was always, no, there will definitely not be a narrator … There are just so many people who have actually lived this story who tell the story so much better than I ever could. So then the question just becomes how do you not include yourself on screen, but also acknowledge the fact that, of course, you can’t make a film without influencing the edit, and each person’s biases come into that. Through the process of talking about the film I try to acknowledge that it’s very much a collaborative process. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle that we are still very much in the process of putting together. And so, it’ll kind of be just an ongoing conversation with Kendal and with the community. And, in the end, we’ll come up with what we come up with. And, like any piece of art, it’s going to be subjective in its own ways.

TSD: How have you thought about artistic appreciation in creating this film?

LG: We really tried to take inspiration from Kendal’s entire lifetime of creating art into how we process this film and how we were editing the film. We’re seeing the film, basically, as a canvas and Kendal is the subject but the material, which goes into that canvas, is from the entire century, nearly a century, in which he has lived … Hopefully, it’s a little bit more artfully done than the average documentary.

TSD: What does winning this Sundance grant mean for you, your team and the film?

LG: Grants we’ve applied to, in previous years, had questions about the legitimacy of Kendal’s story. And this changes that, because it’s not just a Sundance grant, it’s a Sundance grant in combination with Sandbox Films, and Sandbox Films is dedicated to telling stories about science … The fact that Sundance and Sandbox Films both have kind of signed on to the process of creating this film via this production grant lends it a credibility that in some people’s eyes we didn’t have before. And that is important to open some doors to funding and to public distribution in a way that those doors were very much closed to us previously. So it gives us access to a wider audience. And that’s our goal in the end.

TSD: What do you want the next steps in your filmmaking to look like?

LG: I hope to eventually have a production company that’s capable of producing multiple films like this; I’m collaborating with people from around the world. Right now we have about half of my production company based in South Africa, where I lived when I filmed “The Creators,” my first documentary, and I think there’s immeasurable benefit that comes with collaborating [across] borders, and with people from different countries and continents, and so my hope is to be able to continue doing that into the future.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Contact Kirsten Mettler at kmettler ‘at’ stanford.edu.