A “Borat” sequel was always going to face some challenges.

The original 2006 film relied on the element of surprise. Sacha Baron Cohen’s creation, Kazakh journalist Borat Sagdiyev, wormed his way into rodeos, dinner parties and meetings with politicians like Alan Keyes and Bob Barr. Because nobody besides Baron Cohen and the production team knew the persona was a farce, these unscripted, real-life encounters proved illuminating. Not only did Americans tolerate Borat’s anti-Semitism and antiziganism (ostensibly customary in his faux-foreign culture) out of reflexive politeness, but they were emboldened by his blatant bigotry to express their own deeply racist and homophobic beliefs.

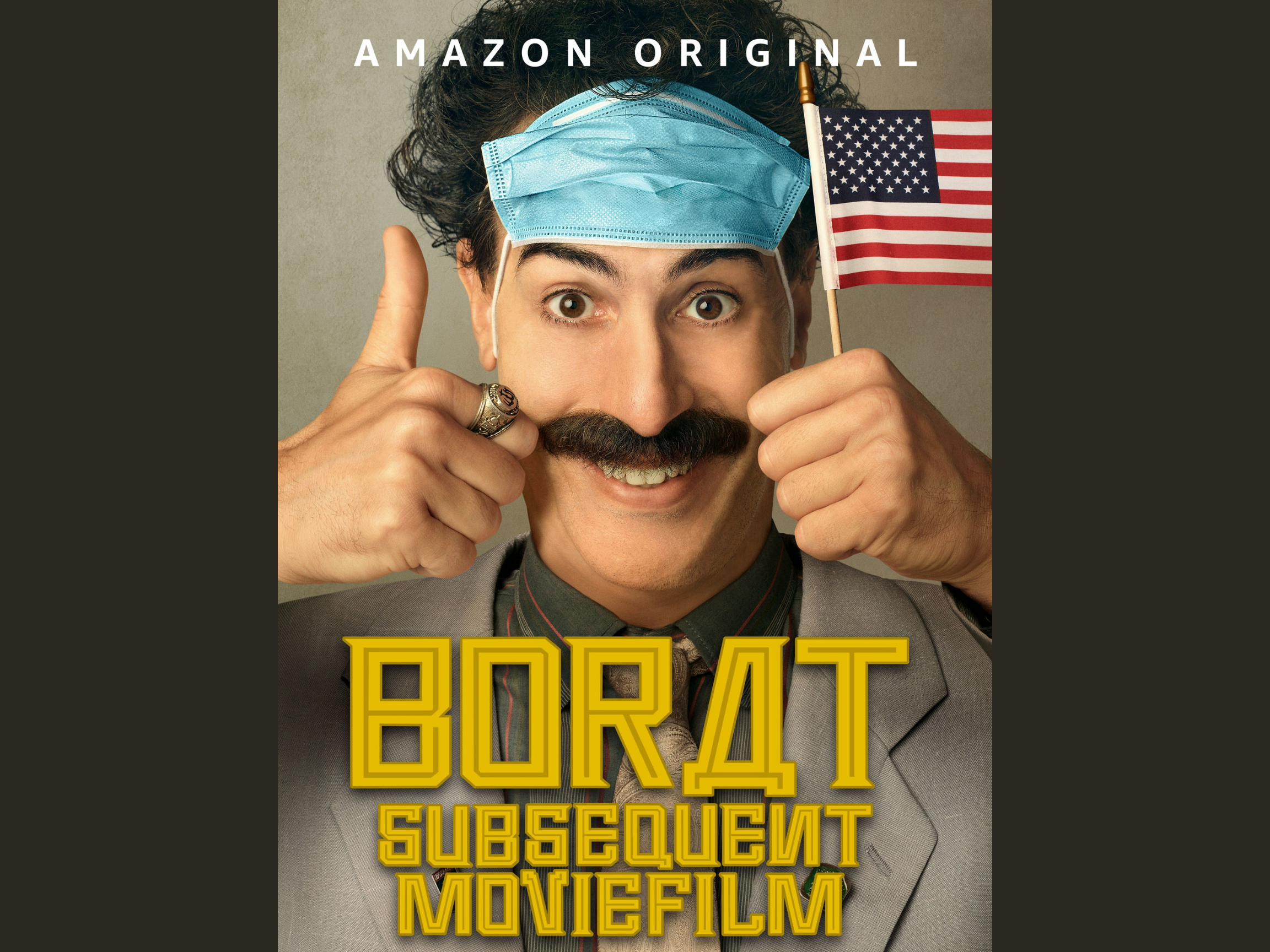

But now, 14 years later, “Borat” has established itself in the modern comedy canon. And its eponymous character — with his thick mustache, gray business suit and catch-all Eastern European accent — has become too iconic and recognizable. How could a Borat revival elicit honest responses from people if they were already in on the joke?

One of Baron Cohen’s solutions is the art of disguise — Borat masquerades as “typical” Americans, including John Chevrolet, Professor Phillip Drummond III and, of course, President McDonald Trump. But the second, more effective solution is the introduction of a new character: Borat’s 15-year-old daughter, Tutar (Maria Bakalova in a star-making turn). Bakalova’s anonymity allows Tutar to take the stage at a Republican women’s club assembly and secure an interview with Rudy Giuliani. And, although not included in the final cut of the film, she recently infiltrated the White House. As Tutar, Bakalova is utterly fearless and her comic timing is on par with Baron Cohen’s.

In fact, thanks to the addition of Bakalova, “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” (now streaming on Amazon Prime Video) eclipses its predecessor in some respects. The first film’s narrative momentum came from Borat’s lust after Pamela Anderson; his motivation to find and marry her served as a loose framework to link his various, random interactions with people across the country. Here, however, the story is more coherent — Borat comes to America to “gift” his daughter as a bride to Vice President “Mikhael” Pence. Since the relationship between Borat and Tutar is well-developed, the movie’s turning points actually hold emotional weight. Baron Cohen and Bakalova have an easy chemistry, so their scripted scenes together feel worthwhile, not merely obligatory to form a narrative throughline.

Whereas the original “Borat” examined xenophobia in a post-9/11 “US and A” in the thick of its War on Terror, “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” turns its attention to misogyny in the Trump era. Unlike Borat’s quest to locate Anderson, Tutar has no agency in her search for a husband — she is being offered by her father. This sequel, for all its deliberately flagrant instances of sexism, understands the nuances of gender power imbalances. Tutar is coached by an experienced sugar baby, considers breast implants and idolizes “Queen Melania.” In one of the movie’s best scenes, Borat and Tutar visit a pro-life crisis pregnancy center. (The clinic, Faith for Fathers, advertises on its website that “[its] goal is to help dads leave a Godly legacy”.) In a series of miscommunications, Borat obliviously implies that Tutar is pregnant and that he is the father. The pastor they meet with advises, “God doesn’t make accidents.” Furthermore, the film’s most buzzed-about sequence — the compromising culmination of Tutar’s interview with Giuliani — addresses head-on the misogyny and objectification women must navigate in the professional world.

But even this “scandalous” exposé isn’t so shocking. The idea that our political leaders could be gullible and crooked is hardly a revelation. A decade ago, it was unexpected to see Americans espousing such overt hatred; today, we no longer need Borat to draw out these horrifying responses — they have become normalized in a news cycle that puts its hands up in outrage one day and moves on the next.

That’s not to say that this sequel has nothing of value to add. When Borat shelters in place with two QAnon conspiracy theorists, they contend that the Clintons drink the blood of children — that this belief is somehow less startling to viewers than Tutar’s proud public display of her “moon blood” is pretty incisive cultural commentary on the stigmatization of women’s issues. And hearing Americans cheering to “chop [journalists] up like the Saudis do” and “gas [scientists] up like the Germans” is certainly appalling. But what do these episodes really tell us? Do they change anyone’s minds?

The original “Borat” was not the most well-constructed story, but the improvised feel was part of its charm and it shone as a brilliant satire. Though “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” is a solid comedy anchored by two exemplary lead performances, the 2020 edition of Borat simply does not have the same shock value as its 2006 counterpart.

Is “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” an accurate portrayal of this hectic year? Probably. But will we look back on this sequel as an insightful time capsule, or as an outdated flick of little consequence?

Contact Jared Klegar at jkklegar ‘at’ stanford.edu.