California Propositions 22 and 24, which deal with the gig economy and data privacy respectively, passed with bipartisan support and double-digit majorities last week.

Proposition 22 allows “app-based rideshare” companies — such as Uber, Lyft, Doordash and Instacart — to treat gig workers as independent contractors, saving them from having to pay for benefits afforded to formal employees. Proposition 24 amends California’s landmark 2018 Consumer Privacy Bill, creating a regulatory body to enforce the provisions of the law. Stanford professors said both votes were largely expected, but offered insights into the causes and effects of each initiative.

Proposition 22

California voters voted for Proposition 22 by a substantial margin, 58.38% to 41.62%. The measure classifies app-based drivers as independent contractors, excluding them from a California law which classifies gig workers as employees and entitles them to minimum wage, overtime protections, paid sick days, workers’ compensation benefits, and unemployment insurance benefits. Ride-share companies had largely failed to provide these benefits.

Supporters included the so-called taxi apps such as Uber, whose CEO said that their services would become “more expensive” had the bill not passed; opponents including former U.S. secretary of labor Robert Reich said the bill could “ gut years of progress on worker protections.”

Early on, support was unclear. October polls indicated 39% of likely voters planned to vote “yes,” and 36% planned to vote “no.” One quarter of voters were undecided.

After political strategists told executives at Uber, Lyft and Doordash that they would need to spend big to change those odds. With over $200 million in the bank, the campaign shattered California records, becoming the most expensive ballot campaign in the state’s history.

Given all the money at hand, Iris Hui, a senior researcher at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, wasn’t surprised by the decisive vote.

“By late October, it was pretty clear that it would pass,” Hui said. “Prop 22 supporters outspent the opponents by a factor of 100, literally,” Hui said. “That money actually made a huge difference.”

Political science professor Bruce Cain said that despite California’s reputation for being “pro-union and democratic,” he believes the vote largely came down to personal experience with a highly regulated taxi business.

“I think in the end, it comes down to the popularity of these companies — I don’t know that it’s the money that mattered,” Cain said. “Uber and Lyft and other car companies offer a service that was badly needed, partly because the taxi business was too limited to people that had taxi medallions.”

Stanford law professor William B. Gould IV raised concerns about the bill, saying that it relegated gig workers to “second-class status,” in an interview with Stanford Law.

“Under the new law, gig workers get 30% reimbursement for car expenses — half of what employees get — and about 70 to 80% of medical care for more senior workers,” Gould said.

These exemptions only apply to what bill calls “app-based drivers.” The bill defines “app-based drivers,” as either (a) an individual who provides delivery services through an online-enabled application or platform or (b) an individual who uses a personal vehicle to provide prearranged transportation services for compensation via a business’s online-enabled application or platform.

Industry-specific exceptions have a history of failure in California, according to Cain.

“The insurance industry tried a similar thing about twenty years ago, but it failed because they were hated,” Cain said. “The same thing happened with PG&E — people don’t like them.”

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi publicly justified the specific exemption by appealing to job-creation. If the proposition hadn’t passed, Khosrowshahi wrote in the New York Times, “rides would be more expensive, which would significantly reduce the number of rides people could take and, in turn, the number of drivers needed to provide those trips.

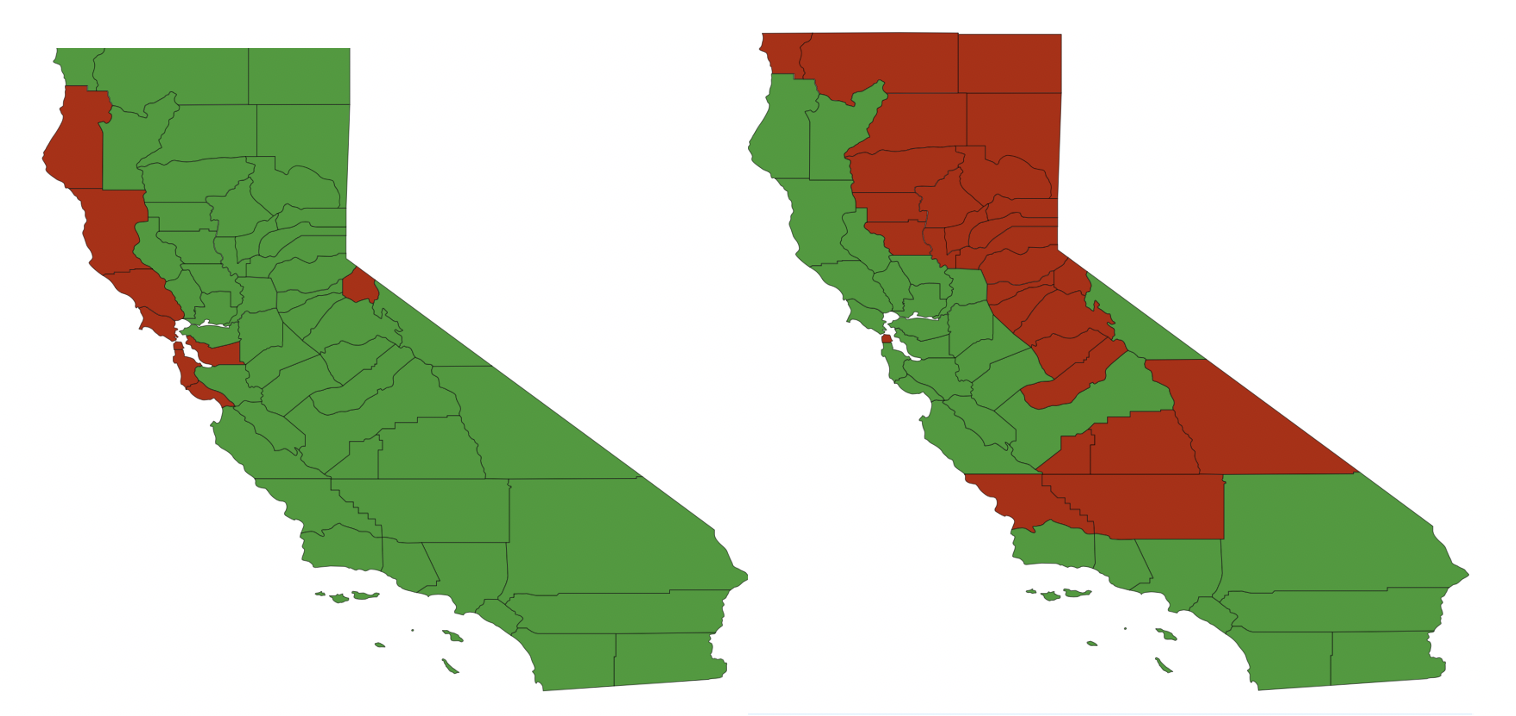

A number of prominent Democrats have come out against the proposition on the grounds that it could spur other industries to try the same technique. Many voters still crossed ideological lines, with a number of blue counties in southern California supporting the measure.

President-elect Joe Biden and vice-president-elect Kamala Harris opposed Proposition 22. Biden has publicly called the gig economy giants “unacceptable,” tweeting that they were “trying to gut the law and exempt their workers.”

Proposition 24

Privacy law Proposition 24 comes at the heels of the 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act, a landmark bill largely considered the “most extensive” privacy law in the United States.

The bill will use taxpayer dollars to create the California Consumer Privacy Agency, which will implement and enforce consumer privacy laws. If companies don’t comply with the rules, the new agency also has jurisdiction to impose fines.

The initiative, which was backed by 2020 presidential candidate Andrew Yang, passed by a margin of 13%, with 56.09% voting “yes” and 43.91% “no.” Yang has supported the measure on the grounds that “compliance [with regulation] would shoot up because all of a sudden the tech companies know we’ll actually be looking at the treatment of our data.”

Hui said the results largely fall in line with the values of California voters, who she describes as placing strong emphasis on privacy, citing the 1974 addition of the right to privacy to the state’s Declaration of Rights. “Privacy has always been the priority for voters,” she said.

Despite the support, a number of high profile advocacy groups urged opposition to the measure. In its voter guide, the American Civil Liberties Union urged Californians to vote against the proposition, calling it a “fake privacy law.”

“Instead of increasing protections, it requires people to jump through more hoops and adds anti-privacy loopholes: exceptions for big business, less protection for workers and more power for police,” the guide read. “Prop 24 benefits big tech and corporate interests but leaves vulnerable communities the least protected.”

Because many of the enforcement mechanisms have yet to be ironed out, Hui said “the devil is really in the details.”

“Voters generally don’t really spend a lot of time studying the propositions. They mostly go with the title and the description in the voter guide, and it’s up to California legislators to do the rest,” Hui said.

Contact Yash Dalmia at yashdalmia ‘at’ stanford.edu and Iyshwary Warren at iwarren ‘at’ stanford.edu.