The mass shooting that left six Asian women dead in Atlanta, Ga. last month captured headlines and shook Asian communities across the country amid a reported rise in anti-Asian violence since the pandemic began.

But anti-Asian hate violence did not begin with COVID-19. The Daily’s Data Team analyzed hate incidents against Asians at Stanford and across the nation in the years leading to and during the pandemic.

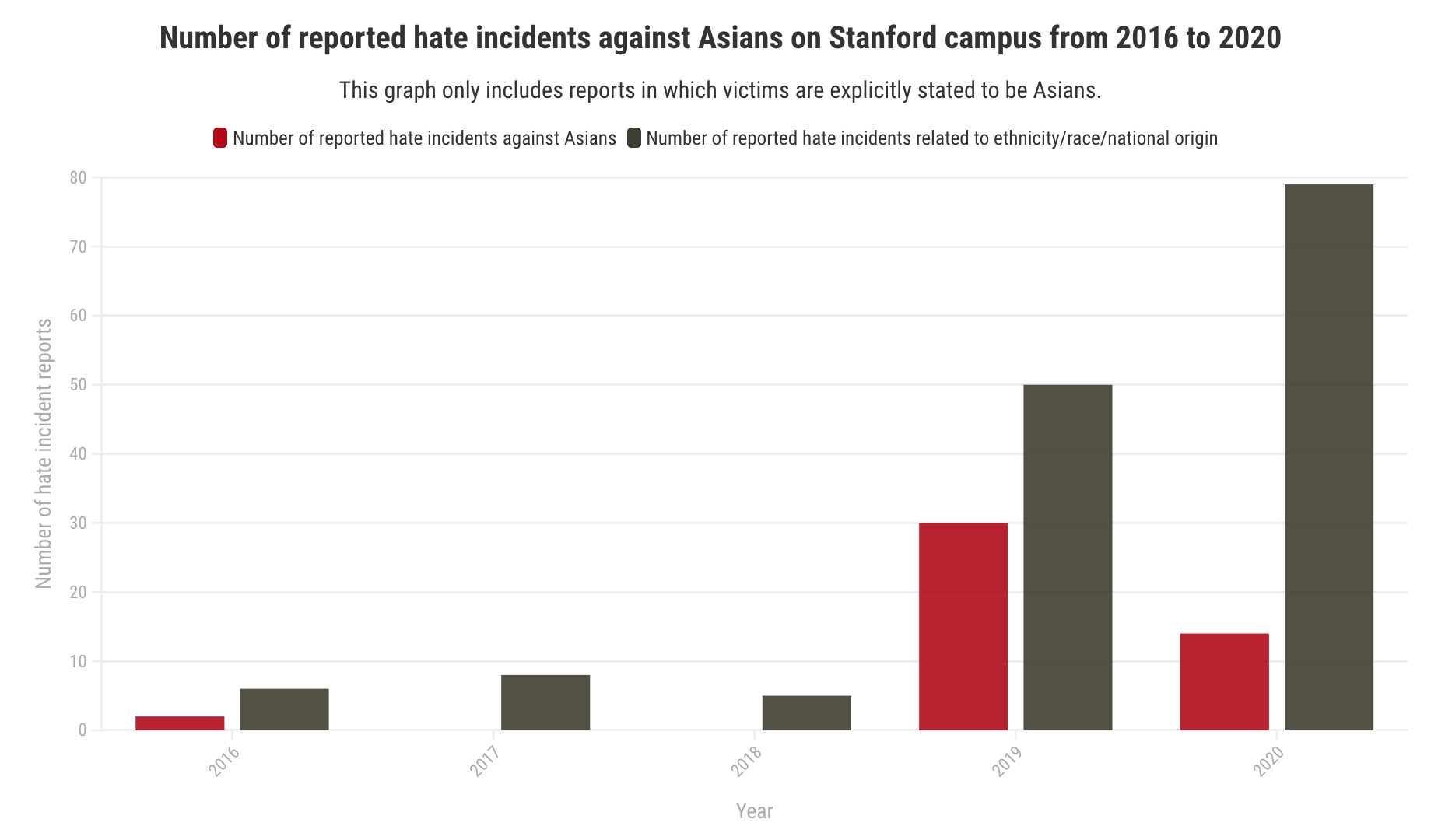

The number of reported hate incidents at Stanford campus targeting Asians jumped from 2018 to 2019, the year before the pandemic hit, according to The Daily’s analysis. A preliminary compilation of last year’s data, which is yet to be fully gathered and published, indicates a lower number of reported hate incidents against Asians in 2020.

Nationally, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes has been increasing since the mid-2010s, according to FBI data. But preliminary analysis of scattered police data shows that the number has shot up since the pandemic, while the number of overall hate crimes has fallen slightly.

Hate incident reports against Asians at Stanford were up even before the pandemic

According to the Stanford Department of Public Safety’s annual report on hate violence statistics, 30 of the 50 total incidents related to race, ethnicity and national origin in 2019 — which accounts for 60% of the total — were against Asians. The reported hate incidents include both hate crimes and violences as defined by the state laws, as well as non-criminal hate violences.

An example of a reported hate crime is one in which the suspect shouted racial slurs and shoved the victim while she was riding her bike. An example of a reported non-criminal hate incident is one in which an older person on a bicycle yelled “so many F-ing Chinese” to an Asian student.

Asians at Stanford – including students, postdoctoral scholars, professoriate faculty and staff – accounted for about 21% of the total population in the school year of 2020 – 2021, according to the IDEAL dashboard.

Emelyn A. dela Peña, Associate Vice Provost for Inclusion, Community and Integrative Learning, told The Daily she also “noticed that the number of reported hate-based incidents directed toward Asians and Asian Americans increased notably in 2019.”

She pointed to three potential factors that contribute to the recent uptick in racially or ethnically motivated hate-based incidents: an actual increase in those incidents, a greater awareness of the harm caused by the incidents or more encouragement for community members to report such incidents. “For example, the university sent three messages to all students on this topic in May, October and November 2019, the same year we saw the uptick in reporting,” dela Peña wrote in an email.

Data also shows that the number of hate incidents related to race, ethnicity or national origin in general jumped in 2019. While the official statistics for 2020 have not yet been released, dela Peña said that her preliminary data compilation for the year showed that “the number of reported cases in 2020 increased from previous years” as well.

“The number of reported cases is likely less than the number of actual cases because not every incident is reported. This is true during COVID or not,” dela Peña wrote.

Based on dela Peña’s preliminary data analysis, there were a total of 79 Acts of Intolerance (AOI) reports — which are filed to report unfair and adverse targeting — related to race, ethnicity or nationality in 2020. Among those, 14 were targeted to Asians and three of those were elevated to hate crimes. The number of Asian-targeted hate violence cases is fewer than that in 2019. The incidents in the AOI reports are reflected in the Department of Public Safety’s annual report.

dela Peña noted that this number may be incomplete, as her team wasn’t able to compile all sources of reports, and many of these reports refer to the same incident.

Number of Asian hate crimes has been increasing nationally since the mid-2010s but has surged since the pandemic

Hate crimes categorized as having “anti-Asian” bias spiked in 1996, with a count of more than 350, then decreased steadily until 2015, according to The Daily’s analysis of the FBI data. But since 2016, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes has been increasing rapidly. There were 115 such crimes in 2015 and 2016, which increased to nearly 200 in 2019. The data for this analysis includes 29 hate crimes that were motivated by multiple biases (for example, anti-Asian and anti-Jewish biases).

The national hate crime data may not capture the full extent of hateful incidents against Asians due to reasons such as insufficient data collection, barriers to reporting and inconsistent definitions of the term “hate crime.”

The FBI has not yet published its annual hate crime statistics for 2020. But a preliminary analysis of scattered police data by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, revealed that anti-Asian hate crimes increased nearly 150% in 16 of America’s largest cities in 2020. During the same year, hate crimes overall declined by 5% in 18 major U.S. cities (including the 16 largest ones).

“We’re seeing a historic surge [of anti-Asian hate crimes],” said Brian Levin J.D. ’92, a professor of Criminal Justice at California State University, San Bernardino and the center’s director.

“Asian people are being beaten now,” Levin said.

Stop AAPI Hate, a reporting center founded at the onset of the pandemic to track the scope of hate incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, announced that it received reports on 3,795 incidents between March 19, 2020 and February 28, 2021 — a much larger number than what is generally captured by the FBI data.

A majority of the incidents, more than two-thirds, involved verbal harassment. Shunning was the second most common, at 20.5% of incidents. Physical assault followed with 11.1%. Some of these reports, such as certain acts of verbal harassment or of shunning, may not be characterized as “hate crimes” by the FBI.

“Part of [the violence against Asian Americans] is a long history, but part of it comes from the cultural and political rhetoric that was being pushed during the Trump presidency,” said William Gow, a lecturer in American Studies and Asian American Studies whose research focuses on Asian American history, film and popular culture.

Gow said Asians have been “oftentimes stereotyped as being perpetual foreigners” despite some of them having lived in the United States for generations, conflating the wide spectrum of identities that Asian Americans and Asians living in the United States hold. Simultaneously, in the past years, “Donald Trump during his presidency really pushed anti-immigrant sentiments,” Gow told The Daily.

“It makes sense that the cultural kind of conditions are there for an increase in anti-Asian violence,” Gow said.

Awareness about discrimination and crimes against Asians surged mostly this March

Google Trends measures the relative search interest on its platform within a specified time frame, in which a value of 100 indicates when the search term was the most popular over that period. It could serve as a proxy for awareness about certain topics.

According to Google Trends, the search interest for the term “Asian hate crime” experienced a slight increase in mid-March of 2020 — around the time the pandemic was beginning in the U.S. It then skyrocketed last month, coinciding with various accounts of violence against Asians and a barrage of social media posts condemning them.

Of the past three months, search interest for the term “Asian hate crime” peaked on March 18, two days after the fatal shooting in Atlanta, Ga. On the other hand, the search interest for the term “Xenophobia” reached its zenith on Jan. 27, the day after the White House published the “Memorandum Condemning and Combating Racism, Xenophobia, and Intolerance Against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.”

The search interest for “Xenophobia” also jumped sharply on March 18, the same day “Asian hate crime” peaked.

There was a smaller bump in search interests for both terms on March 31, around the day an elderly Filipino woman in New York was abruptly and repeatedly assaulted by a man. One of the security guards of a nearby apartment lobby closed the door on the scene. The attack was captured in a security camera video.

Available resources on campus and moving forward

The Asian Americans Activities Center (A3C) serves as a main resource and community for Asian students, staff and faculty on campus. On March 18, A3C sent out an email condemning the Asian American violence and inviting students to attend a reflective healing session.

Stanford also put together a page on the Student Affairs website that provides resources and context around the harassment against Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders during COVID-19. “Racist behavior is antithetical to our values and something we have been working to eliminate on our campus,” dela Peña said.

Going forward, a “more robust support for something like Asian American studies, or more robust support for ethnic studies more broadly, might facilitate a decrease in kind of anti-Asian incidents on campus,” Gow suggested.

Stanford currently offers undergraduates a major and a minor in Asian American Studies, which is part of an interdepartmental program called the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (CCSRE). But the program is weaker than those of peer research universities in California, Gow told The Daily.

Gow said “every single one of these Research 1 universities in California has multiple tenured Asian American Studies faculty members within a full department of Ethnic Studies, Asian American Studies, or American Studies and Ethnicity,” and “many of these universities offer graduate degrees in Ethnic Studies or Asian American Studies.”

In contrast, “Stanford has an undergraduate program with no tenure or tenure-track faculty housed directly within Asian American studies or CCSRE,” Gow said. Affiliated tenured faculty members are housed in other departments such as History or Comparative Literature.

There was a recent push for the departmentalization of Stanford’s African and African American Studies (AAAS) program – which was also part of the CSRE – as an effort to promote diversity and end racial injustice at Stanford. Gow said he is supportive of the initiative, and the university “could also provide additional support to Asian American Studies and the other programs under CCSRE.” School of Humanities and Sciences spokesperson Joy Leighton told The Daily that “decisions about academic departments and degrees offerings are made by the faculty.”

“As a lecturer that teaches Asian American Studies, I see that there’s way more students who want to take these classes than there’s actually space in my classes,” Gow said. “There’s definitely room to grow the program, but to grow the program, the program needs more financial resources.”