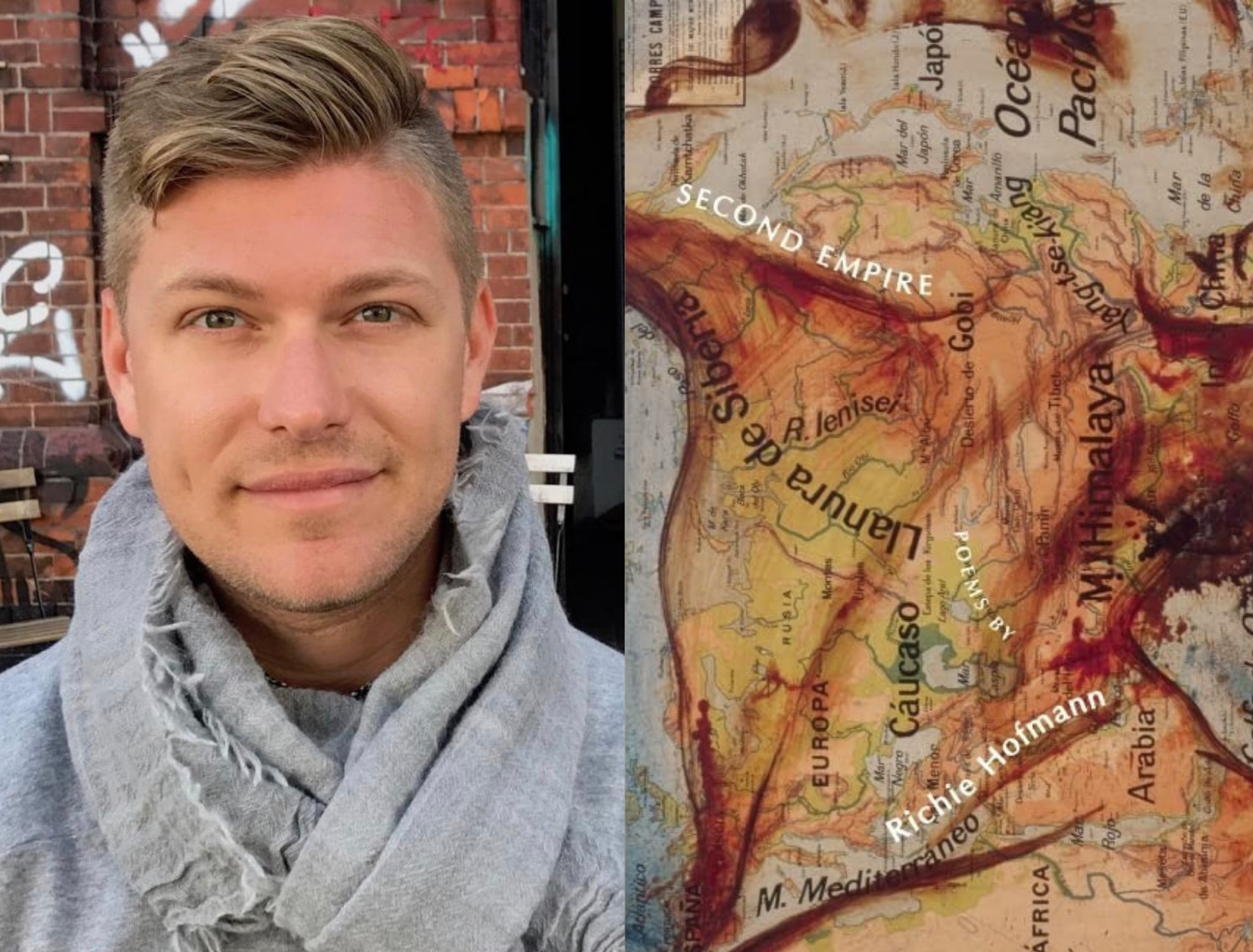

In the Creative Writing Program’s latest installment of the “Poetry in Conversation” speaker series, lecturer Richie Hofmann read from and discussed his 2015 poetry collection “Second Empire.” Through self-reflection and conversations with lecturer Keith Ekiss and the audience, Hofmann provided sincere advice on how to improve as one continues their journey as a writer.

The event first began with Hofmann reading from the collection. The first poem, “Egytian Bowl with Figs,” was inspired by an artifact at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University. He explained that the poem explores his fascination with the artifact and how it was preserved for thousands of years. After reading the poem “Description,” Hofmann reflected on how rereading poems trapped him into the time he wrote them: He could remember where he was when wrote them — even as far back as 10 years — what the weather was and the specific feedback he received from friends and family. Lastly, he chose to read the poem “After” due to its romantic images. His selection and explanations captivated me as I found a new appreciation for the poems and the emotions they evoke.

After reading, Hofmann spoke about his own path as a writer. While his main art medium is currently poetry, his practice and mastery came after studying other art forms, such as visual art, theatre and music. He further explained that poetry allows him the freedom to speak about many disciplines and interpret them without in-depth knowledge. For instance, if he wanted to explore the mind of an art historian, he could write from the perspective of one for just 20 lines. Poetry allows the poet to indulge in several crafts without the pressure to further knowledge.

When asked about how his writing has changed and if he would rewrite any of the pieces from “Second Empire,” Hofmann admitted that he would have made changes. However, he touched on how each poem is a record of the time at which it is written, and that the impulse to revise is only natural because he himself has changed in the time that has passed.

“I want to change,” Hofmann said. “I want to transform [and] change from what I was and what I am.”

As he continued to discuss his identity as a poet, Hofmann also talked about his poetic influences — a process he described as “absorption.” He cited T.S. Eliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral” and James Merrill’s “Divine Comedies” as two of the formative works in his introduction to poetry.

According to Hofmann, essential to being a poet is simply reading more and more poetry, from all eras and languages: what he calls making a “poetry family.” In creating this family, Hofmann shows how poetry, while a solitary act, can still foster community. Not only do poets interact with friends for feedback in the present, but they can also use the inspiration from past works to communicate with their poetic predecessors. This allows writers to participate in something larger and older than themselves.

His method on revising, which I found familiar in my experience with editing my prose, is workshopping and accepting feedback from “poetry friends” while also reciprocating feedback. Hofmann also encouraged writers to throw out lines, large chunks or even whole poems and just start over if it didn’t feel right. “You won’t miss it,” he reassured us.

Lastly, responding to a question about what to do if you feel that you are repeatedly telling the same story, Hofmann encouraged poets to write through the story, but to also reflect on how they can transform it with each telling. In other words, “you do you … but do yourself differently.”

Prior to reading “Second Empire” and attending this event, I had less of an appreciation for the work that goes into poetry, preferring the craft of prose. However, Hofmann’s approach to poetry was inspiring and made me look at poetry as a method of change. I will certainly use his advice and work as part of my own “poetry family” to continue to grow as a writer.

In an earlier version of this article the Creative Writing Program was inaccurately referred to as the Creative Writing Department. The Daily regrets this error.