This article is a collaboration with Stanford Prison Renaissance, an interdisciplinary group of Stanford students, staff and faculty who partner with incarcerated people over the phone and in visiting rooms to produce an annual zine.

May of 1998. Mother’s Day, to be exact, and Lamavis Comundoiwilla was scrambling to find the perfect gift. While incarcerated at Corcoran State Prison, he took out his art supplies and created a hand-drawn card. Amazed by his talent, his mother urged him to pursue this newfound passion, and a few days later, his father wrote to his cell and offered to buy more drawing supplies.

This is the origin story of Comundoiwilla’s artistic journey: A Mother’s Day gift catapulted him into a world of creativity and expression, and with this story, the underlying essence of his artwork is rooted in a devotion between mother and son. You can tell by the way Comundoiwilla speaks about her. His voice lights up. He narrates his story with the same energy of a John Coltrane melody: bursting with nostalgia, sincerity and love. Every artist has their origin story, and Comundoiwilla’s is one that exudes a profound admiration for the women in his life.

Fast forward to 2018, and after being transferred to San Quentin State Prison, Comundoiwilla began painting again. Alongside his art practice, he devoted himself to intensive research and applied historical knowledge. While diving into military history, he discovered the ways historical dictators, such as Hitler and Napoleon, suppressed and destroyed ethnic art. “Artists were the first news reporters of mankind,” says Comundoiwilla, and so he believes in the need to recover this powerful tool. During his study of modern art movements, Comundoiwilla came across “Goldfish” (1902) by Gustav Klimt and was struck by inspiration. It became his favorite painting. Originally titled “To My Critics,” Klimt’s painting opened people’s eyes to the corruption of the Viennese government and Catholic Church. Comundoiwilla believes that contemporary art carries the same potential for political advocacy and social change.

His investigation of modern art grew more multifaceted when Comundoiwilla realized that painters like Picasso and Dalí drew inspiration from Ancient Egypt. “Why do we refer to Picasso as the father of cubism,” he asks, “but we don’t acknowledge the Egyptians who he got his inspiration from?” Because of this question, he strives to reclaim the stolen, eradicated art of precolonial civilizations.

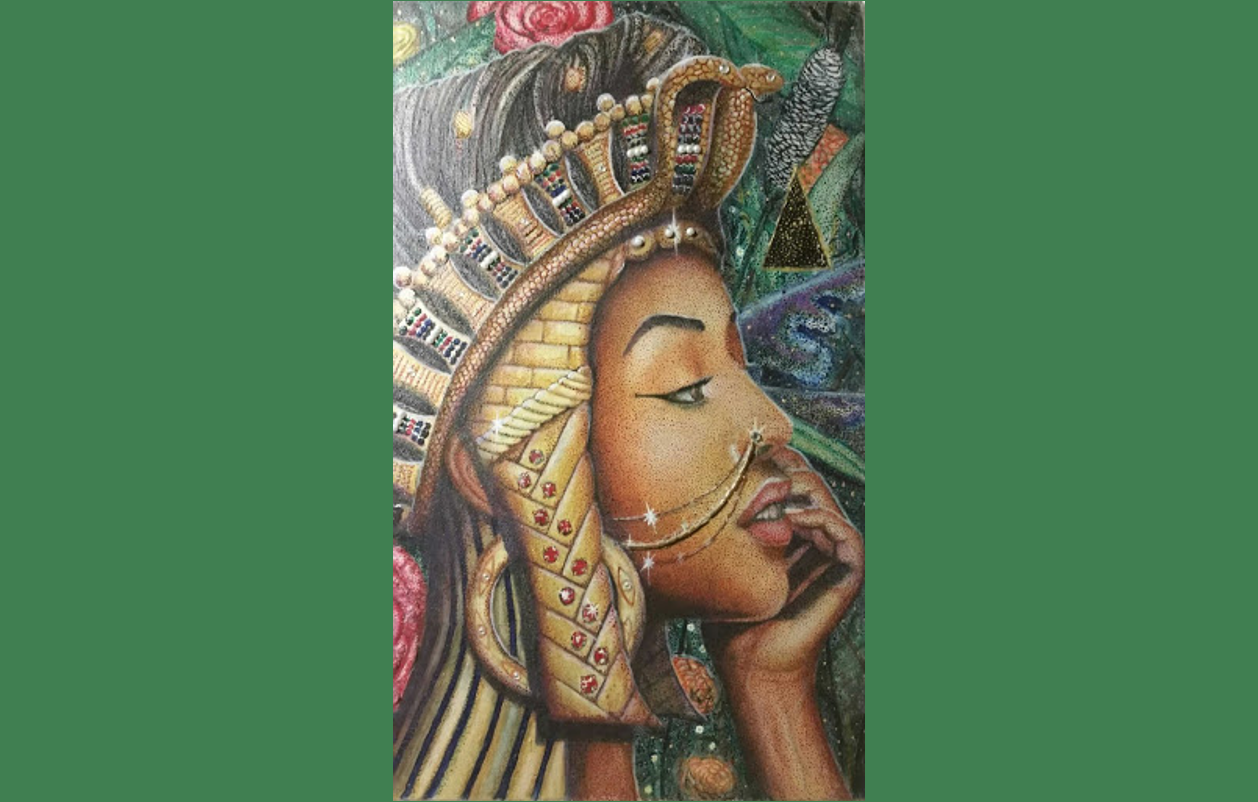

Comundoiwilla made it his mission to study pre-colonial African history. In this endeavor, he discovered long records of the greatest matriarchal societies to ever exist, such as the Candaces of Meroe who were the queens of the Kingdom of Kush. Unlike the patriarchal nature of Western societies, the Candaces exemplified the strength of a matriarchal governance. Appalled by the hypersexual, degrading portrayals of women in Western mass media, Comundoiwilla turned to the Candaces for a radical muse. He paints Black women, inspired by the historical queens of Meroe, because he wants to change the way we depict them in today’s society. His painting, “Amani Candice,” is a vibrant recreation of Kandake Amanirenas, the queen who defended her kingdom against the armies of the Roman Empire.

Stylistically, Comundoiwilla’s paintings are Fusion — a technique created by the artist himself. When people told him that everything in art has already been done, he fought back and proved them wrong. “Fusion is when you use dots and strokes together to create a painting,” he explains, “and it’s always done with intention. Every geometric symbol has a meaning.” In “Amani Candice,” Comundoiwilla takes the Eye of Providence, which is seen on the one-dollar bill, and adds his own message to the Masonic triangle. Breaking away from the fraternal organization, he transforms this masculine symbol by painting diverse eye shapes that belong to women of color.

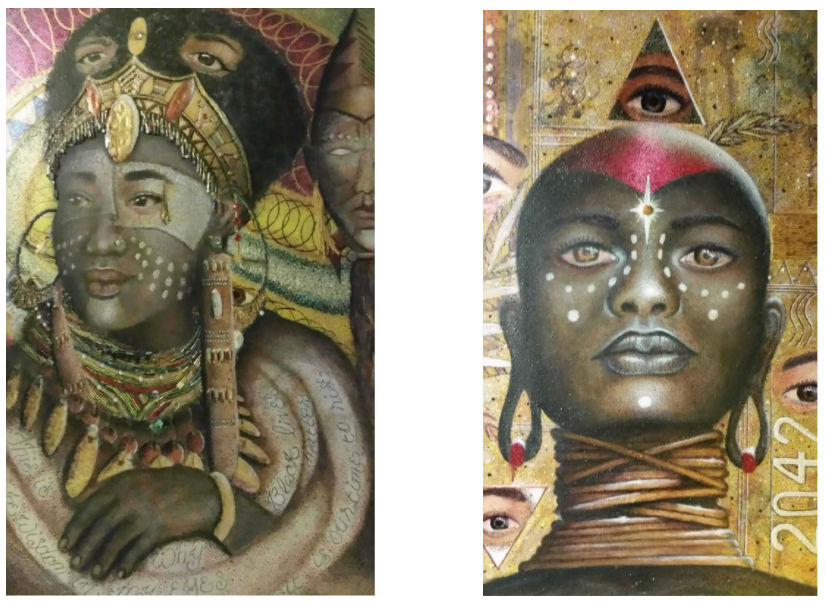

When asked about the future of Fusion, he was bold and resilient in his answer: “Black excellence in history is pushed out of the conversation, but today, I won’t let that happen. I want to be in control of my art.” His paintings represent the future of the United States in which the ethnic minority will become the majority. We see this hope in “New American Patriot,” in which Comunoiwilla replaces Uncle Sam with a multiracial, indigenous woman. She is adorned in pre-Columbian regalia, and in her eyes, “BLM” is mirrored in reverse. This is to depict how Black Lives Matter is not only a movement; it is also a reflection of the new generation of voices that is working hard to transform our nation.

“2042” is a tribute to what the future will hold in the United States of America. “This country was stolen from the Native Americans and the Mexicans. It was built by Black slave labor. The industrial age would not have ever happened if the railroads weren’t created by Asians,” says Comunoiwilla, “and I can’t wait for this nation to belong to the people who built this country.”

Today, while Comundoiwilla paints in his prison cell, the world is undergoing a global pandemic and the injustices of systemic violence. In San Quentin alone, The COVID-19 outbreak has resulted in 2,900 infections and 32 deaths.

“I survived the coronavirus, but I lost many friends. The media wants to show how people fight in prisons, but they don’t understand that we’re a close community. Even if we’re not getting along, we’re still close. Death affects everybody. Devastating does not even explain what it was. It’s an understatement,” Comunoiwilla describes.

Because of the pandemic, prison has become an even darker space: “It’s been a mess. Unimaginably a mess.” During this tragic era, filled with grief and loss, he turns to art for a sense of peace. As the pandemic forced the world to pause and reflect, Comunoiwilla took this time to cultivate new works of art as a mode of healing and expression.

Throughout his time in prison, art has allowed Comunoiwilla to process difficult challenges and memories. “Can you imagine someone judging you for the worst day of your life? For the rest of your life? That’s what it’s like to be a convicted felon — to continuously be wearing a scarlet letter. There has to be a better way for broken people to remerge into society. I’m not a guy who’s trying to hurt people. I’ve changed. I’m not the same person as I used to be at 25. Art has a lot to do with that. It gave me solace and peace. It taught me how to understand myself.”

For Comunoiwilla, grief entered his life when his daughter passed away at only 11 months old. “I realized that I’ve become an angry person when my daughter died from a lack of healthcare. Pre-existing conditions made her ineligible for the healthcare that she needed. That’s why she died. My daughter died over the issue of money, so that’s why I started robbery.” As Comunoiwilla reflects on his past, it is telling that his role as a father was intensely complex and sacred. “A lot of dads are not there for their children, but that was not me. She woke up on me, lying on my chest, every morning. We laughed. We played. She was my daughter. My everything.”

During this difficult period, Comunoiwilla questioned God, his faith in humanity and the reason for being. “If there is a God, what kind of God allows a child to die?” he asked. However, he soon found a revelation that pushed him further to express the complexity of life and art. “The idea of God is omnipresent, and if God is in everything and everywhere at all times, is God in you? It was a reclamation to me. My sadness is something I had to live through, and God experienced it with me. All the time I didn’t believe in God, it was like not believing in myself.”

Through his grief, healing and continuous reckoning with life, Comunoiwilla’s message can be felt by all artists and struggling individuals, all navigating humanity’s unique battles and striving towards a path of healing: “Religion is to believe in yourself, and art is a religious experience.” Now, all of his paintings are dedicated to his daughter, mother and strong women in his life. Through intricate strokes and detailed patterns, his paintings serve as a devotion — a revelation that transforms art into a spiritual, political and cultural creature.

Comunoiwilla’s artwork will be featured in Stanford’s Prison Renaissance Zine. Prison Renaissance connects incarcerated people with a community of artists, forming a collaborative space in which art fills the divide between the general public and those who are in prison. To transform the ongoing dialogue of criminal justice reform, Prison Renaissance strives to center and amplify the voices, leadership, artistic practice and academic work of incarcerated people.

Previous issues of Prison Renaissance Zines:

Incarceratedly Yours, issue ii: Don’t You Forget About Me

Incarceratedly Yours, COVID-19 Issue