This article was originally drafted in May 2021 and has been lightly edited since then.

At its heart, a catastrophe necessitates, and provides, an opportunity to reassess inefficiencies. Between the darkest hour of the 2008 financial recession and the end of 2019, for example, American publications jettisoned roughly half of their newsroom jobs. Google, Facebook and other Internet titans forced into obsolescence the average newspaper’s primary source of revenue — print advertising. Unsurprisingly, as technology has only improved in its ease of use, and as the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged the planet, more and more publications are turning into casualties — especially the local ones. About a decade ago, undergraduate enrollment dropped for the first time since the Civil War, and now thousands of institutions in higher education are faced with a new enclave of setbacks, from which many will not recover. And though shopping habits were already changing, it seems that the past year has hammered the final nail in the coffin for malls and other retail locations.

That all is what capitalism is supposed to do, I suppose. The system is at its best when it allocates economic resources to where they will be used most efficiently. Customers moved from Blockbuster to Netflix. Shareholders in Payless ShoeSource chose to invest in Zappos instead. But is efficiency the be-all and end-all? This particular shift that we are observing now could be chalked up as “creative destruction” — essentially the deliberate disruption of current industry in favor of something more sophisticated — but I’m not sure that Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of economic “growing pains” is of solace to most. Indeed, he considered it “the essential fact about capitalism,” but Schumpeter also described it as “incessant.” If colleges have budget cuts, fewer students will be able to afford an education, and with the vanishing of local news outlets, political polarization will likely rise. These outcomes would undo a lot of social progress that has come from the past decades.

The flipside, of course, is that efficiency offers continuously improving convenience. Nowadays, you can pay someone else to walk the dog or go grocery shopping. There’s no need to remember to buy a new tube of toothpaste if you automate it with an Amazon Prime subscription. Even the process of finding a date has been streamlined. Gone are the days of venturing to the bar and trying one’s luck. Now, your soulmate is supposedly a swipe away. It wouldn’t be baseless to claim that the first fifth of the 21st century has accelerated humanity’s innovative sprint toward posthumanism. In fact, we may one day look back at the ongoing pandemic as an inflection point of sorts.

As most of us were forced to assume a virtual life, what is accepted as someone’s identity is now distinct from the body or a particular location. We more or less still socialize and function as before, sure, but the constraints that these makeshift digital solutions come with have given rise to new expressions of selfhood. A virtual background goes in place of a bracelet or ring. Animal Crossing goes in place of heirlooms, weddings and conferences all at once. Then comes the metaverse. But don’t get too comfy on your couch. These luxuries should not serve as a means to drown out the stark reality of masked, physically distanced interactions we have faced in the real world. If enough people approve of the lifestyle we’ve so quickly adapted to, who’s to stop companies like G95 from seizing the opportunity to sell us “biohoodies” and make us even less of ourselves? If this behavior of showing less of one’s humanity becomes stylish, I’m not sure if I want to imagine what comes next.

Stephen Hawking once was quoted saying, “Work gives you meaning and purpose, and life is empty without it.” Whether you agree or disagree, it is true that almost everyone’s self-concept is made in part from the contributions they make to society through work and service to others. True, such contributions may provide money — but more importantly, they fulfill basic psychological needs: social contact, status and time structure. COVID-19 seems to be shifting us to a more automated, more algorithm-driven, more mechanical future in which robots usurp us from our jobs. Of course, new industries will create new jobs, but those are likely to require more skill and education than the average person has today. Not everyone will be spared.

That’s the ugly truth. Not everyone will be able to gracefully transition to a new field of work. But the problem really isn’t that many hardworking blue-collar workers will lose their jobs. The problem is that we’ve created a society in which we will need our jobs more than they need us. At least I’d imagine most people depend on their livelihoods for a sense of purpose without thinking about it much. But in a post-work world, they will have to think then, if not already. For the time being, it is an interesting thought experiment, because discovering how one would substitute employment with purposeful activity provides insight into the self and its needs when all the other noise is removed.

Thus, the constant pursuit of efficiency — go, go, go! — is more of a frenetic, self-destructive obsession than a cardinal feature of human spirit and innovation. Why? In economic theory, efficiency is categorized as a problem that arises in a stagnating economy — not a solution. Yet most people, I assume, are unaware of that: collectively we’ve become masters of efficiency. To utilize resources at the lowest cost, history has seen employees, managers, departments, organizations, industries and whole sectors worked to the bone, in many creative ways, to a point where economic growth is measured by the tiniest marginal gains in efficiency.

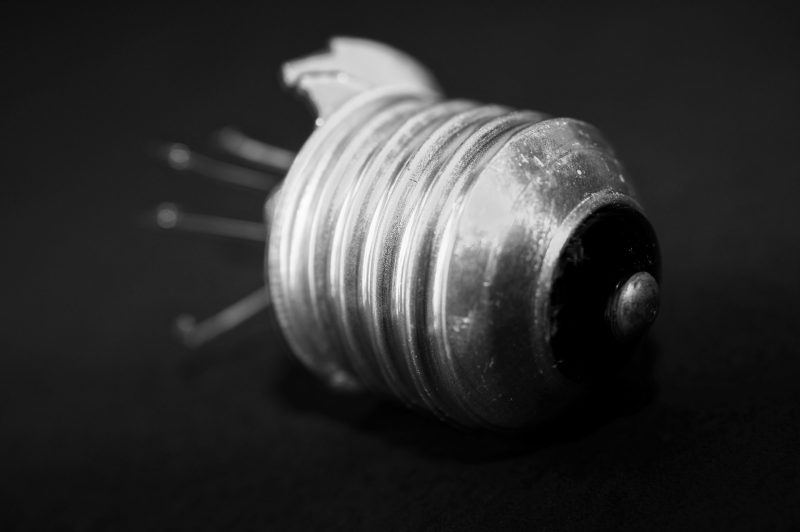

By itself, efficiency is not what an advanced economy ought to be concerned with. Productivity is what an advanced economy ought to be concerned with. Far different from merely making things cheaper, productivity is about making things better. The printing press, the incandescent light bulb, the automobile, the internet — these aren’t only conveniences. They are earth-shattering moments in history that truly and dramatically change people’s lives. Productivity, as opposed to efficiency, creates whole new markets, ideas and cultures. It enables the Everyman to do more, not just do something faster or through a proxy.

Instead of manipulating people over and over with growth hacking, maybe it’s time to reinvest in the physical world in 2022. Where are all the flying cars? When will quantum teleportation become a reality? Maybe infrastructure will matter to voters again if they come out of their houses for some fresh air. But when everyone, including the architects of such inventions, is trapped in an unrelenting battering of Zoom calls day in and day out, it’s no wonder that something as trivial as Snapchat is now considered of “importance” to businesses.

Silicon Valley is not evil. If that were the case I wouldn’t be a prospective computer science major. The point is that the easy choice in this situation is to continue what we’ve done — single-mindedly measuring economic gains and falsely lionizing apps as agents to bring humanity into a higher civilization — whereas the difficult choice, also the right one, is to invest in a future that prioritizes humans over software.