“What’s your major?”

This is the question that every Stanford student is asked as often as what their own name is. Over the past 10 years, the most likely answer has become Computer Science (CS), or one of its close relatives such as Symbolic Systems (SymSys) or Mathematical and Computational Science (MCS). These three majors made up over a quarter of all undergraduate degrees conferred in 2019-2020 and are still drawing students year on year.

Despite the university’s apparent emphasis on a liberal arts education, students and faculty across all academic disciplines feel that Stanford is a tech school. This is unsurprising: Stanford alumni and faculty have built many of Silicon Valley’s giants, and this symbiotic relationship with the tech industry forms the basis for Stanford’s prestige.

Many students come to Stanford precisely for its famed entrepreneurial culture, groundbreaking CS research, and direct route to Silicon Valley; these students very well may find their co-founders here, conduct research with a professor pioneering a field of artificial intelligence and walk out of Stanford with a slew of Big Tech job offers (Stanford is the 2nd largest feeder into Silicon Valley jobs, after UC Berkeley).

But there are other, less desirable phenomena happening here: the metamorphoses of humanities and arts majors into computer science majors, and the industrial pipeline that shuttles CS majors directly into Big Tech.

The Big Switch

Sherry Xie ’25 came to Stanford intending to major in History. She has since switched to CS.

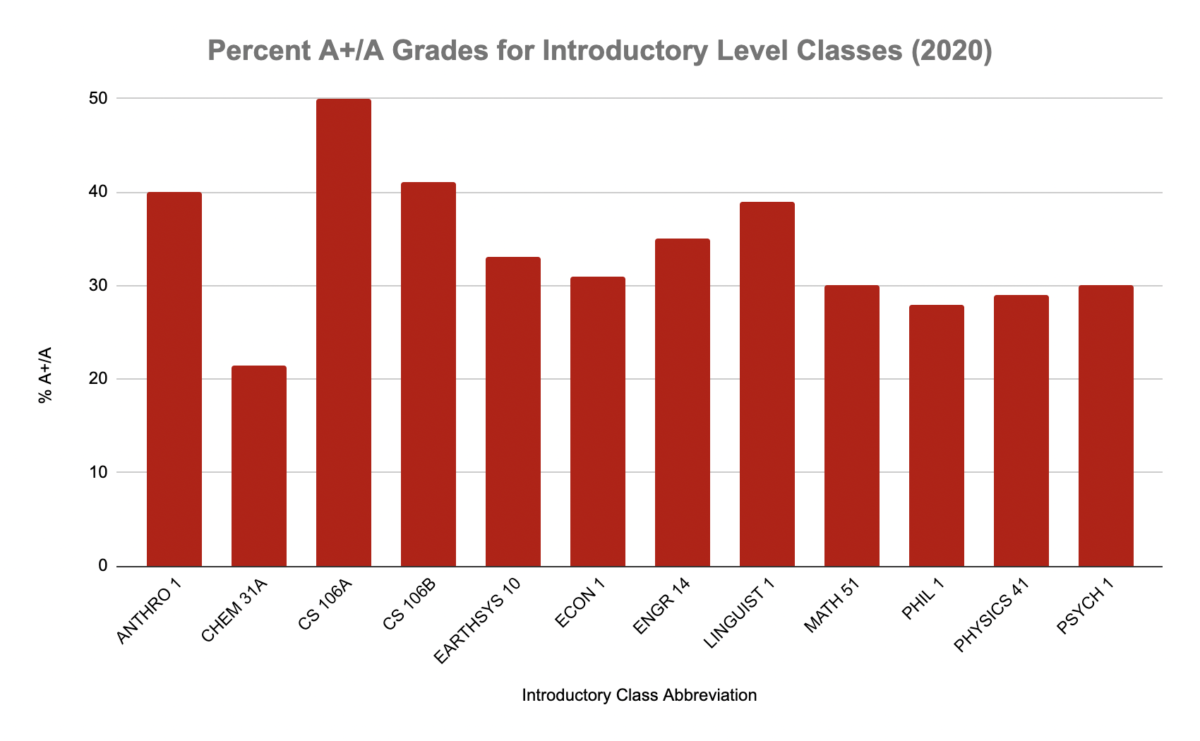

“What really changed me was taking Math 51 and CS 106A first quarter,” Xie said. Unlike the intimidating philosophical discussions in SLE — the residential freshman humanities intensive that Xie also took — “the CS intro classes really make you feel like you can do them. And that’s the spell which means I keep going with it.”

The messaging of introductory CS courses strongly encourages students to continue with CS regardless of their final grade. Lecturers frequently emphasize the real-world applications of every skill taught, as well as a clear path forward with the major. The 106 series in particular offers extensive student support through the section leading program and additional LaIR office hours, creating an inclusive and exciting learning environment.

Professor Mehran Sahami, the Associate Chair for Education in the CS department, attributes the rate of major-switching in part to the fact that many students don’t have the opportunity to learn computer science before they get to college – these students may be wary of declaring their interest before coming to Stanford.

The ability to quickly see results is also a motivator for pursuing CS, according to Nahum Maru ’25, also a CS major. “After just 106A or 106B, you’re able to create something significant, and you see how much people around you can do just five miles down the road,” he said.

Some of Maru’s friends — also freshmen — are in seed-funding rounds for their blockchain startup, and others are making significant contributions at burgeoning companies. “So I think there’s definitely a culture where the most successful people [at Stanford] now seem to be CS majors,” he said.

But as a result of this support and encouragement to pursue CS, Sahami said the Big Switch has created “capacity challenges for faculty” — nevertheless, he reiterated the department’s commitment to not institute a cap on the number of CS majors.

The CS student to teaching faculty ratio which was nearly 20:1 as of 2019, almost five times the University-wide student-faculty ratio – means that CS students have far less direct contact with faculty and tend to not have an intimate classroom experience. Instead of getting to know your peers or their ideas through discussion, you spend most of your time listening to lectures and completing p-sets, often on your own.

What does this mean for other majors?

“The most encouragement I received at the beginning was to do CS 106A and Math 51,” Xie said. “I don’t think I see that big of a push toward humanities intro classes.” She noted that overflowing waitlists for introductory humanities courses, in contrast to capless intro STEM classes, discouraged interested students from pursuing that discipline.

Some underclassmen also recount being advised by upperclassmen to just “get through” PoliSci 1 in order to access higher-level classes. One prospective International Relations (IR) major felt that the Introduction to International Relations (PoliSci 101) mostly involved learning specific jargon and theories from the textbook without much understanding of their context or real-world applications. This experience discouraged him from taking further IR classes, not wanting to “risk” the 5-unit commitment and miss out on taking classes that seem more applicable.

To counteract the pull of the CS department, other departments could benefit from making their introductory classes more welcoming, accessible and exciting. Sahami pointed out that the CS department, particularly in the 106 series, expends great resources considering how to teach material in the most useful and engaging way possible. “Our courses are constantly under revision, and our pedagogy is always being re-examined,” he said.

Introductory classes across all departments might be enhanced by increasing the network of TAs to support more students, or employing more faculty in that specific domain. If lecturers for introductory courses are especially charismatic and passionate about teaching, students might be more encouraged to take further classes. Finally, there should be a clearer sense of what classes suit what level of experience. For instance, there is no explicit introductory class for History or English. Another student majoring in IR said that she was frustrated that she hadn’t felt challenged by any of her classes yet, so she is taking CS 106A this quarter. If she had been told to take a specific higher-level course to begin with — as CS majors are told to skip to 106B or 107 and beyond depending on their experience — she may have found academic fulfillment outside of the CS department.

An Interdisciplinary Education

These concerns over the growing imbalance in undergraduate majors should not be answered by any cap on the number of CS majors. Instead, we should focus on encouraging students of all backgrounds to be more interdisciplinary.

“I don’t think anyone, including the Computer Science department, wants to see Stanford become the Stanford Institute of Technology,” Sahami told me.

Andrew Benson is a CS Master’s student who teaches two classes (CS 107A and CS 9) while also being a full-time senior software engineer at Google. His view is that we should focus CS education towards non-CS majors. “It’s more beneficial for society for people of other disciplines to have the tools of CS, to help them do better in their disciplines,” he said. “Because CS is preparation for CS. But other disciplines will make society better.”

In an effort to help CS majors expand their worldview beyond the tech bubble, Sahami co-founded CS 182: Ethics, Public Policy, and Technological Change with Rob Reich and Jeremy Weinstein, both of whom teach in the Political Science department.

He explained that the university, although theoretically supportive of multidisciplinary work, still needs to recognise the greater effort faculty across departments must put in to effectively teach together. Many departments only offer faculty partial credit for co-taught classes.

The CS 182 professors managed to negotiate more appropriate credit from the University. “If those kinds of things were more actively encouraged across the university, we might see more collaboration along those lines,” Sahami said.

In 2018, Marc Tessier-Levigne announced three presidential initiatives. The first, recognising Stanford’s outsized responsibility in shaping the technology of tomorrow, is named Ethics, Society & Technology. In response, the CS department has in recent years placed growing emphasis on integrating an ethical education into its courses.

However, student reception has not always matched the faculty’s well-intentioned efforts. Ethics lectures are emptier than programming content ones, and homework questions are often seen as too undirected, leading to the perception that ethics is simply an accessory to the core of the class. One CS major who did not want to be named said that “[ethics] is an important feature, I guess, but not what I enjoy.”

A Pipeline into Big Tech?

The second presidential initiative is for Purposeful Engagement with Our Region, Nation & World. What do we consider purposeful engagement?

In 2019, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and several other major newspapers covered Stanford students’ #NoTechForICE protests, which criticized Palantir for providing technology to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. According to the NYT, a campus activist group called “Students for the Liberation of All People” hung a banner reading “Our software is so powerful it separates families” at Palantir’s offices.

I asked 15 freshmen majoring in CS whether they were aware of this protest, or the activist group. None of them had heard of either. The sentiment of these protests certainly lingers on campus, but the movement seems to have lost momentum among newer students, especially considering how the pandemic fractured outgoing classes from incoming ones.

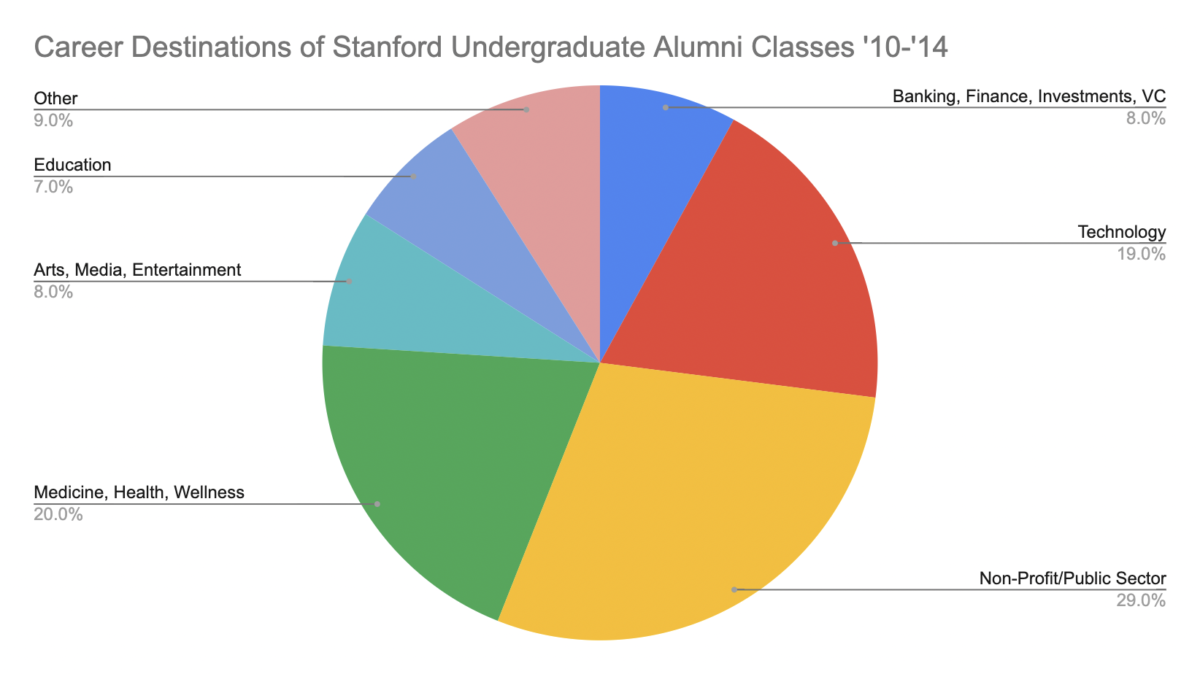

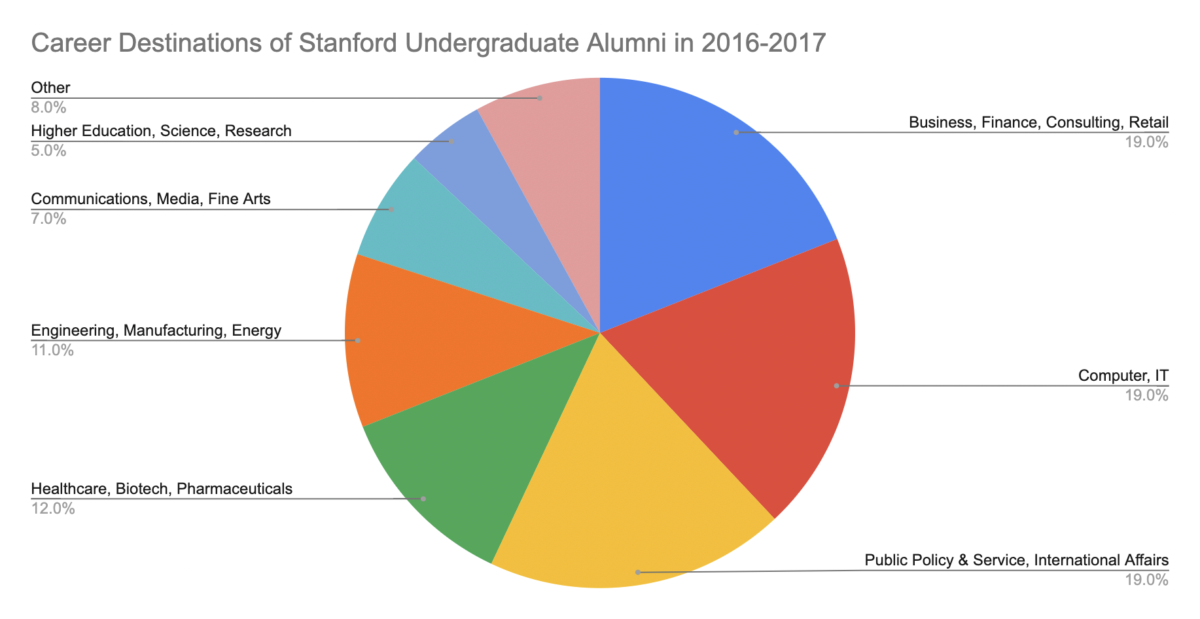

And it’s all too easy to ignore that cognitive dissonance: in the competitive spirit that got many of us here in the first place, students compare salaries and name-recognition, prestige and exit options – in Sahami’s words, “trying to optimize their careers.” We’re already immersed in the landscape of lucrative tech jobs by geographic proximity alone. Then factor in information and recruiting sessions, career fairs, vast internship programs, conversations and endless LinkedIn stalking. All of which help make Big Tech “the default,” according to Nadin Tamer, a junior majoring in CS and minoring in Education, who is co-president of Code the Change and interned at Facebook last summer.“You wouldn’t know about these non-profit jobs unless you actually went looking for them,” she said. “Whereas you do get a lot of exposure to Big Tech stuff, just by being here and listening to people’s conversations.”

So what about ethics? In 2022, you’d have to be woefully under-informed to believe that Big Tech companies are forces for pure good in the world. But there remains a contentious debate over whether it is better to effect change from within or outside of those companies.

Some members of the Stanford community believe it’s possible to generate ethical change from within a company, and some say that individuals are essentially neutral, as their work cannot significantly contribute to nor change the operations of a massive corporation like Meta.

Benson argued that change is possible when many potential employees coordinate. “Collectively, you can say ‘okay, let’s try to encourage software engineers on the whole to not work for certain companies’ if we think that will help them change their practices. Or we can encourage students to form new companies that will be more talented and through competition try to change their policies, ” he said. On the other hand, an individual would likely have to “rise the ranks in leadership to be privy to decisions being made at a high level and influence them.”

Many entering Big Tech say that they only plan to work there for a few years, then leave to found a startup, do non-profit work, or pursue their real passion. Some do. Some also grow accustomed to the lifestyle associated with that job and forget what they originally had planned for themselves – much as many students entering Stanford forget the passions and ambitions they had as fresh-faced first-years.

It is, no doubt, an immense privilege to be able to reject a six-figure job. “Working in industry, especially the software industry, provides you with the opportunity to live very comfortably because the pay is so good, and there are many benefits in terms of quality of life,” Benson said. But it would be dishonest to characterize our career options as simply Big Tech or non-profit public service work, with nothing that is more value-aligned in between.

Maru described how, as a CS student from a low-income background, he was initially “enamored” by the starting salaries at the Big Five companies, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft. “I was trying to optimize prestige to eventually get more money to help my family,” he said. However, his viewpoint began to change after seeing how passionate some friends were in pursuing their own projects beyond classes. “If I’m going to go into industry, I’d very much want to work on problems I think are intellectually interesting,” he said. “I also have to think, are they going to use what I’m doing ethically?”

One student may be the main breadwinner for their family; another may need to pay off bills and loans; some may simply, and reasonably, want the financial security and quality of life. Working for Big Tech, as one interviewee put it, is like a “rubber stamp on your resume”; much like the stamp of attending Stanford University, it automatically deems you smart, successful and worthy of further opportunities. The extra credibility conferred by working at Big Tech is no small thing. But are we purely seeking to leverage our education to build clout for our professional lives?

A University Education

We don’t owe it to Stanford to do everything we said we would do on campus. But don’t we owe it to our past selves to not abandon those causes we so strongly advocated for, those passions that we spent so much of our lives cultivating?

We’re constantly told by University administration that we are here for a reason. We were given this education for a reason: to create daring and moving art; to bring communities together; to contribute fresh ideas to a shrinking field of study. It is our choice whether to deliver on that reason.

For recipients of a name-brand “elite” education, getting a job in finance, consulting, or Big Tech is a comfortable route. The actual process of completing the major, writing applications, and undergoing endless rounds of interviews may be painstaking, but you never have to make active decisions: you simply follow the four-year-plan, the corporate flowchart.

Being at Stanford makes it extremely easy for us to default to the safety of the pipeline, but being at Stanford also means we are in the rare position to not do that and still live comfortably. Nobody I talked to for this article or in casual conversation around Stanford cited excitement — let alone doing good in the world —as a reason to work for Big Tech.

How can Stanford balance their commitment to enable students to have agency in their careers with their responsibility to shape the “leaders of tomorrow”?

If Stanford wishes to truly protect a culture of creative and academic freedom, the University must make a greater effort to separate its undergraduate education from the influences of Silicon Valley. Our intellectual freedom to stroll or sprint down different academic avenues should be equal – if so many students who were previously unexposed to CS discover a passion for it, shouldn’t other students who gain similar access to film studies or femgen at Stanford be encouraged to fall in love with that discipline and pursue it through Stanford and beyond?

We must also make an individual effort to change the cultural narrative around these fields of study. One student I talked to in the course of this article told me he was considering several majors: “double E, math, physics, they’re all awesome. But you know, for you they’re probably the same majors.” I’m a prospective MCS major, but in my capacity as a reporter, he assumed that I wouldn’t even understand distinctions between STEM disciplines. There is a common perception among some techies that humanities, social sciences and arts majors are easier and less intellectually rigorous.

Stanford has several possible strategies they could pursue if they want to facilitate a more open-minded and interdisciplinary academic culture, particularly within the world of CS. Classes such as CS 182W, which is dedicated to exploring the ethical and political implications of CS innovations, could be bumped up in the order of required classes — say around when students are taking CS 107, the majority of whom plan to study a CS-related major or minor.

This would help students engage deeply and early on with the ways that technologies they create may affect the world, and have that in mind as they continue developing their technical skills. Currently, such classes, including exploratory WAYS requirements, are notoriously backloaded to senior year where students scramble to fulfill them all in order to graduate. A more consistent integration of this liberal arts education would expose students to new fields of study while they still have ample time to explore them further.

Stanford could even join the ranks of some of its peer institutions in actively encouraging its students to reject the pipeline – and I mean at the highest level of messaging, as when Harvard’s President Faust urged graduating students to eschew the “all but irresistible recruiting juggernaut” in 2008. This may be biting the hand that feeds you, but perhaps we could all benefit from a bolder institutional stance.

What I’m advocating for is intentionality and self-awareness. We are students at Stanford. I’m guessing that most of us chose to come here partly due to the weight that name carries: the prestige, power, and wealth of opportunity associated with our education. Despite pressures from parents and peers, we shouldn’t simply chase – or worse, fall into – the next most “prestigious” thing, believing that everyone around us is doing the same. We have more agency than we think, and our choices become our friends’ choices, our community’s choices. Campus culture is ultimately composed of the sum of our individual decisions.

And we can take a step back to realize that being here has already given us an enormous amount of security. As people with this privilege, we should never sleepwalk through our careers; if you choose to “sell out”— as many students refer to working for Big Tech, finance, or consulting — it should be with the same intentionality and consideration as those who choose a non-traditional route. Life is long, and 2 to 3 years at a Big Tech company certainly wouldn’t define our entire careers — but the choice itself is a signal to others that our personal prestige is more important than our values.

This is not about rejecting CS or Big Tech. It’s about approaching our precious last years of formal education with academic curiosity and intentionality, and remembering that our lives are our own. We own our academic and industrial labor. We own our beliefs and dreams, and have the power to influence the beliefs and dreams of those around us. Let’s act accordingly.