The multiverse has recently been permeating pop culture. From Marvel movies to the 2022 blockbuster “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” it has become wieldy for both entertainment and, in the latter, explorations of immigrant identity. In the Asian Art Museum’s current exhibition, “Kongkee: Warring States Cyberpunk,” Hong Kongese artist and animator Kongkee (Kong Khong-chang) uses the idea to explore a coalescence of past and future that brings objects to life in the museum.

“Kongkee: Warring States Cyberpunk,” on view until Jan. 23, imagines a future in which ancient Chinese poet Qu Yuan’s consciousness is uploaded into Joe, a cyborg, who then continues to live out Qu’s life. Living during China’s Warring States period in the Chu kingdom, Qu drowned himself after the capital of Chu was captured by a rival kingdom, Qin. It is widely believed that Qu committed suicide because he was consumed by the anguish of losing his motherland — an interpretation that gave rise to his prominence in China as a symbol of patriotism. Qu Yuan’s death is now memorialized in the Dragon Boat Festival.

Drenched in vibrant color, the exhibition explores Qu Yuan’s ancient story with a futuristic aesthetic. It combines multiple mediums by threading Kongkee’s animations, comic strips and lenticulars with the Asian Art Museum’s collection of Warring States period artifacts. The exhibition itself unfolds like a comic book. Eschewing labels introducing each work separately, captions for each section of the exhibition tell a coherent story about Qu Yuan’s journey through the future. Topping it off is Kongkee’s 30-minute animated film, “Dragon’s Delusion,” which won the 22nd DigiCon6 Asia Grand Prize in 2020. Through reviving Qu Yuan in the body of an automaton, Kongkee revitalizes ancient Chinese history for modern-day experiences, reinventing the gallery as a liminal space between past and future.

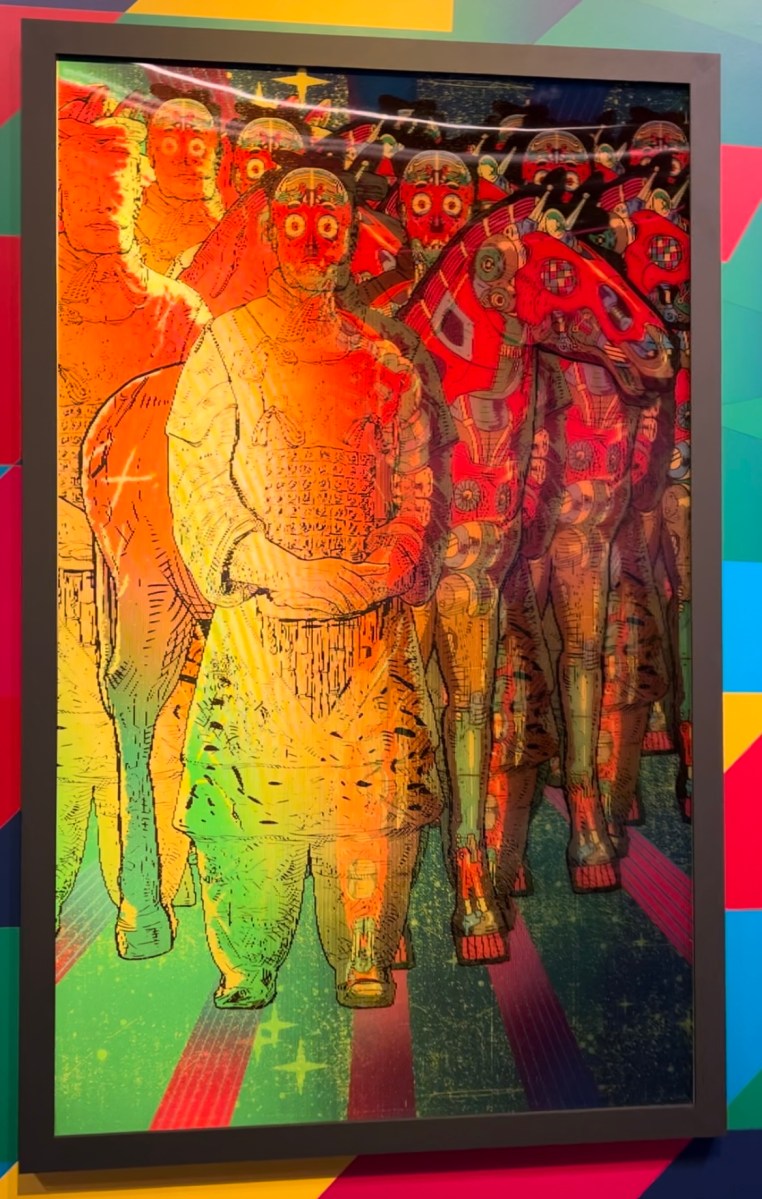

I was transported back to childhood as I stood in front of a glimmering, human-sized lenticular displaying what seemed like neon cyborgs. When I moved, the cyborgs morphed into rows of Terracotta Warriors unearthed from the grave of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of the unified China. Standing at just the right angle, the warriors’ faces cracked into the cyborgs’ mechanical wiring as if held under a X-Ray. In that moment, time folded in on itself — the Terracotta Warriors seemed to be unearthed into a cyberpunk future, while my 23-year-old self stood in America looking at a lenticular that was often seen in playing cards during my childhood in China.

“The whole universe and other universes are coexisting together. The point is, you have to tune them to the right channel,” Kongkee explained. The exhibition invites us to experience wrinkles in time and challenges us to dive into alternate, non-western ways of seeing the world in which time isn’t linear.

To build a continuum between past and future, Kongkee designed four glass boxes displaying Warring States period artifacts submerged in neon light. As the light changes, from purple to green to yellow, the artifacts appear to shape-shift as well, dancing under the discotheque light. Kongkee had designed the exhibition display “to give you a feeling that the object is still alive.”

Kongkee’s vibrant use of color is an aesthetic choice that gains political power when it invites viewers into a nonlinear relationship to the past that takes ancient artifacts out of the museum’s fossilizing and colonial gaze. The Chinese artifacts’ mere existence in an American museum brings to mind instances of looting perpetrated by European countries in China.

“I do feel that [Kongkee’s] use of color and rendering of the electronic landscape decolonize the object because, very often these antique, archaeological objects become trophies the moment they enter a museum — they are positioned under a colonial gaze,” commented Abby Chen, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Asian Art Museum. She sees the potential of Kongkee’s work to liberate these objects.

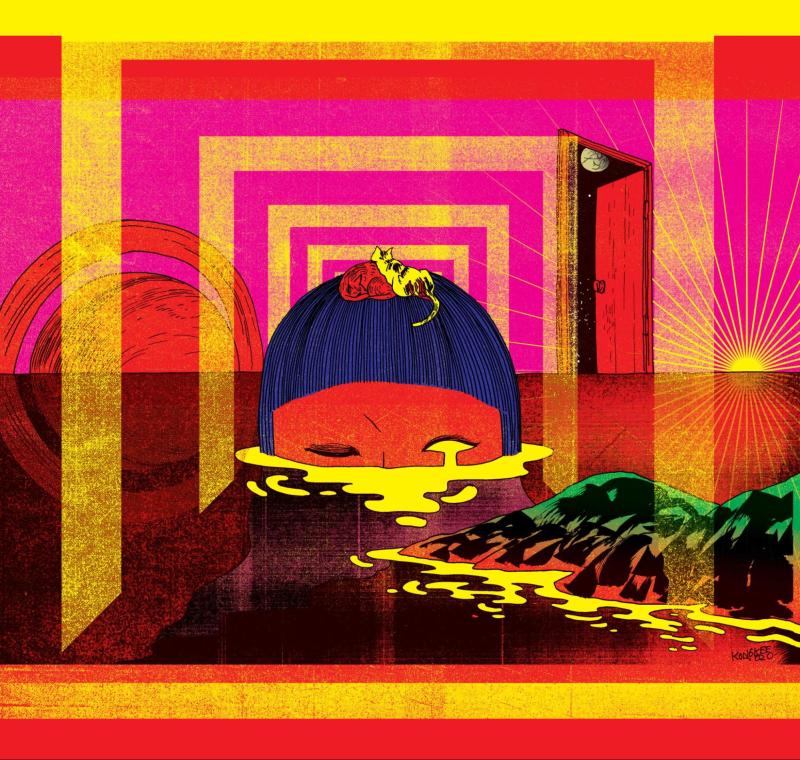

The ancient artifact displays stand in conversation with four towering LED screens on the opposite gallery wall that display four of Kongkee’s comics in motion. In my favorite one, an animated, blue-haired Qu Yuan dips into the water then emerges, all while two sleeping cats nestle on his head.

“[The ancient artifacts and LED screens] break through the boundaries of the time to come together in this party,” Kongkee explained, calling the exhibition a celebration.

Kongkee’s use of popular mediums, from animations to comic strips to lenticulars, breaks through the aura of elitism that museums can carry. He uses mediums that are accessible to everyone to place ancient Chinese stories and artifacts back into the hands of the people. These objects are no longer fixed behind a glass and ossified as trophies of colonial power or relics of an ancient civilization, but presented as living things once used by the people.

The push and pull between suppression and liberation forms a strong underlying current throughout the exhibition. In a gallery behind a large window, some of Kongkee’s works can be seen from the street. Looking through the window at night, passersby can see a man’s shadow floating in a white void; its title is “Am I Drowning or Am I Flying?” Especially when seen from the street below, the shadow looks as if it is flying in the sky. However, the work simultaneously alludes to Qu Yuan’s death in the river, with his body bobbing in the waves. “It’s a tension between two images. When you are flying in the sky, you feel free, but it’s also very close to death,” Kongkee explained.

Kongkee’s multiverse beautifully straddles the tension between suppression and freedom, mute pain and ecstatic joy. Walking through the exhibition is taking a psychedelic journey in time. The effusion of color in Kongkee’s work shocks everything it touches into coming alive.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.