Stanford filed a lawsuit against Santa Clara County earlier this February seeking a partial tax exemption for faculty homes on campus amidst criticisms that the University could do more to help faculty who are facing “unexpected and substantial financial difficulty” due to increased property taxes.

Housing at and near Stanford is already more expensive compared to other university towns in the country. Currently, faculty homes are taxed at purchase price just like the property taxes paid by all other California homeowners. However, the lawsuit argues that on-campus faculty homes are different from most other properties and should be taxed accordingly.

The University’s lawsuit states that the property value of campus homes should be split between “faculty interest” and “college interest.” The property used by Stanford for “educational purposes” is the college interest. At present, there is no distinction: both faculty and college interests are included in the county’s property tax assessment of the campus homes. College interest, which the University alleges is worth about 25% of each campus home’s property tax, should qualify for tax exemptions, the lawsuit argues. The University is seeking a refund on the property tax paid on its college interest.

The legal case specifically seeks a tax refund for one house in the Faculty Subdivision, which some proponents say they hope will establish a landmark case of sorts, enabling the principle of tax refunds to be applied to all faculty housing.

According to the legal complaint, in 2017, the county assessor reassessed newly purchased faculty homes to well above the faculty purchase price — often more than 35% higher than their purchase prices. This high assessment of newly purchased homes created a “significant financial uncertainty and hardship” for many faculty members who own long-term leasehold interests in homes on campus, the legal complaint says.

The subject of faculty housing affordability has come up repeatedly, including in a recent faculty senate meeting. Simultaneously, the issue has attracted the attention of many local residents, including Jenna Mains, who criticized the University for not doing enough to help faculty address affordability concerns.

According to a University statement in February, the Stanford has “exhausted all remedies at the administrative level” to appeal property tax reassessments, including unsuccessful appeals to the Assessment Appeals Board, Board of Supervisors and County Assessor’s Office. The University filed the lawsuit against Santa Clara County to seek clarity on “differing legal interpretations.”

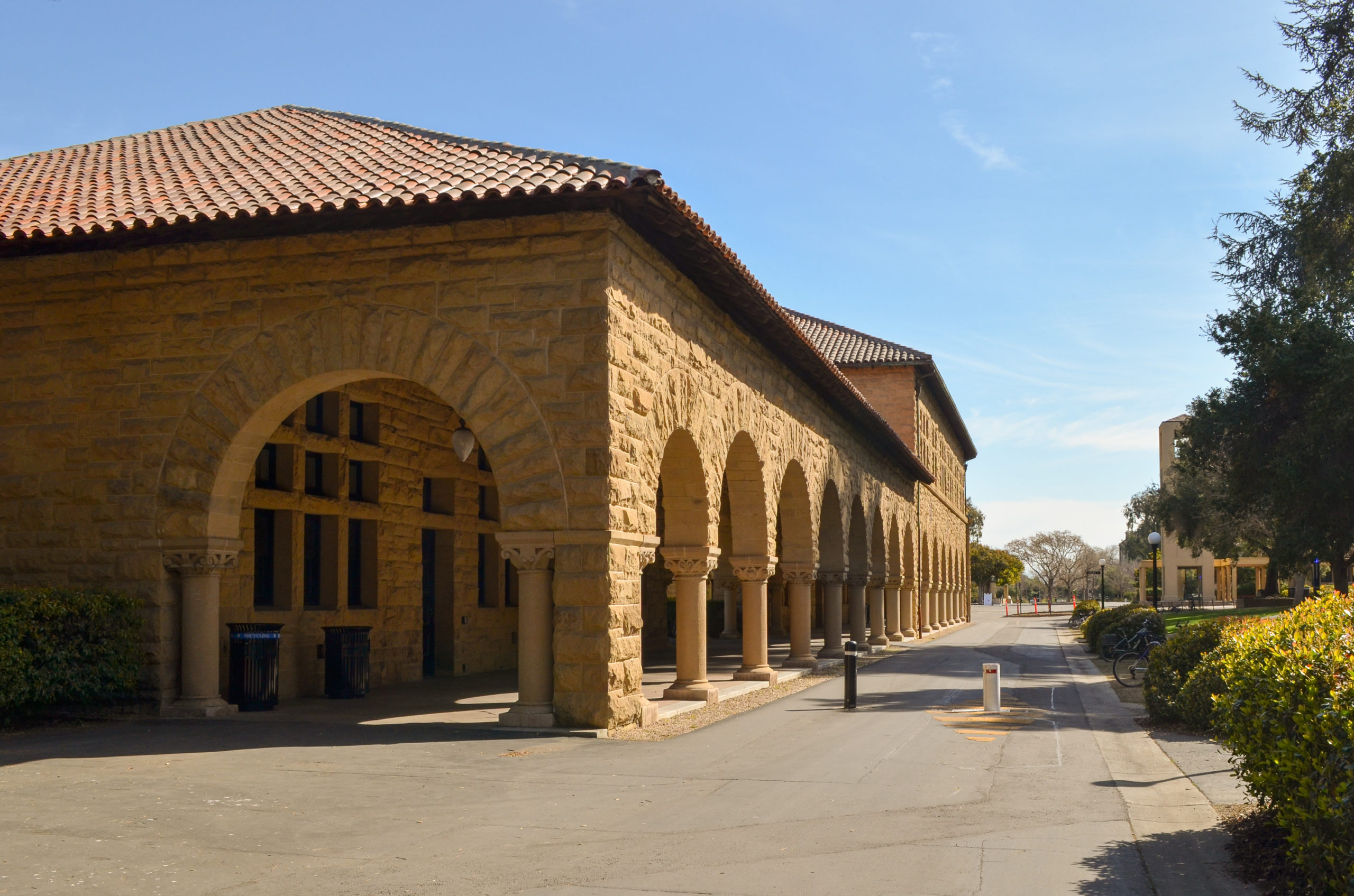

University lands devoted to academic uses are tax-exempt under the California Constitution, under which student dorms, libraries and academic buildings fall. Stanford’s lawsuit argues that faculty homes should also count as educational facilities.

The California courts have “consistently granted this college interest exemption on university-provided faculty and staff housing” because, according to the lawsuit, it is well recognized that such housing is critical to the achievement of a university’s educational mission. According to Stanford’s statement, a residential campus, in which faculty can host dinners, meetings and social events, strengthens the academic fabric of the University and thus should qualify for a partial property tax exemption.

However, the county has argued that faculty homes should be treated like any other homes in the county and assessed based on their market value. County Counsel James Williams disputed Stanford’s definition of “on campus” in an interview with Palo Alto Weekly, arguing that the faculty residences — aside from not having the same educational status as libraries, academic buildings or student dormitories — are not located in the core academic campus.

Steve Staiger, a historian with the Palo Alto Historical Association, told KQED that Stanford is a major employer on the Mid-Peninsula, both for faculty and staff. A 1999 Stanford Magazine article noted that faculty recruitment historically suffered as a result of soaring house prices in the local real-estate market. The lawsuit seeks to address many faculty members’ worries about whether or not the University will be able to house new faculty who might not be able to afford high property tax prices.

In 2021, roughly $15.9 billion of the University’s holdings were tax exempt as a result of Proposition 13, California’s property tax law, which held down the reported value of many Stanford properties. This was the largest tax exemption in the county, Williams told the Palo Alto Weekly.

However, the lawsuit is about alleviating the financial burden faced by faculty, rather than saving the University money, according to James Sweeney, President of Stanford Campus Residential Leaseholders (SCRL) Board of Directors. All faculty living in campus homes pay their property taxes themselves without aid from the University, Sweeney explained.

The University confirmed this, writing that “Stanford derives no financial benefit from the property taxes paid by on-campus homeowners. The taxes are paid directly to Santa Clara County through the Department of Tax and Collections.”

The lawsuit attempts to get a reimbursement of the tax difference for one specific house on 838 Cedro Way, whose original fair market value of $2.97 million in 2018 was raised to $3.06 million after a county reassessment in 2021. Sweeney said that he is hopeful that, if the refund is successful, this legal case will establish a principle of requesting tax refunds for other houses also impacted by high reassessment rates.

All ground leases in the Faculty subdivision are for 51 years, and about 25-30 single-family homes and condos are sold on campus every year, according to University spokesperson Joel Berman. If Stanford’s lawsuit is successful, faculty homeowners will continue to pay the full share of property taxes for their homes, however, for homeowners who purchased their properties in 2017 or after, this rate will be reduced by 25% due to the tax exemption status, according to the University’s statement in February.

Sweeney has lived in a faculty home with his family since 1985, and while his children have since moved out, under Proposition 13, he said that he still pays the property tax reflective of the home’s purchase price 40 years ago. However, the newer faculty he works with can’t say the same.

According to a letter from SCRL’s Board of Directors supporting the University’s legal action, high property taxes create the largest barrier to homeownership for first-time, often younger faculty. However, all campus homeowners are impacted — including faculty wishing to sell their homes, faculty deterred from living on campus due to high costs and prospective home purchasers.

Elaine Treharne, a tenured professor of early English literature, said that she was recently able to afford to buy a condo in the Faculty subdivision towards the end of 2021 after saving up for the past nine years.

Faculty are alert to property taxes when they buy, Treharne wrote in an email to The Daily. Faculty also rely on the University’s initial property tax estimate, which reflects the price that faculty paid for the house. However, Santa Clara County conducts its own appraisal of the house, sometime after the sale, which overrides the University’s initial calculations.

“Our house took a year for their appraisal and it came back as being a 50% greater value than we paid (which we could never sell it for),” Treharne wrote, explaining that their property tax was also reassessed to be higher than expected.

“In September 2022, we were asked to pay almost double what had been estimated; we also had (with no warning, as it were) to pay the outstanding equivalent retrospectively,” Treharne wrote.

These costs, Treharne wrote, continue to impact many faculty members’ monthly expenses, given that these costs were unanticipated at the beginning of the purchase process.

Residents of Peter Coutts, one of two faculty condominium complexes, are an example of how faculty have taken action to better understand the impacts of tax burdens.

Kate Maher, Earth system science professor and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment, has been a campus homeowner since 2008. As part of an initiative to better understand the tax burden, she has collected information and data about affordability issues faced by faculty residents living in Peter Coutts and said that at the condominium complex, “everyone is struggling with affordability.”

According to Maher, while faculty who have owned campus homes for longer pay property taxes according to the initial property purchase price, new homeowners are paying tax based on what the current market value would be in Palo Alto, not on campus. In some cases, that could double their tax bill, Maher said.

Maher said that, because of the reassessments, which began in 2017 for newly purchased residences, 60% of the total taxes paid by Peter Coutts — a 140-unit complex — is only paid by roughly 25 units. This, Maher said, creates a “huge discrepancy” between the median tax bill and what a small number of units are paying because of the tax increase.

“There are folks who are not sure of their ability to stay in their house, and that’s largely driven by the tax situation,” Maher said, explaining that on top of property taxes, faculty must also pay monthly expenses.

Maher said that these monthly expenses, some of which are controlled by the University, have also rapidly increased. “Monthly expenses are, for a lot of people, an enormous concern,” Maher continued. “The price of water that’s controlled by Stanford has gone up considerably … fire insurance has also gone up.”

The Daily has reached out to the University for comment on whether the amount faculty pay for these monthly expenses is controlled by the University, and if the University is doing anything to decrease the cost of monthly expenses due to increased faculty concerns about affordability.

However, according to the lawsuit, campus homeowners don’t receive the typical benefits an off-campus homeowner would when buying a house. The lawsuit argues that the county’s property reassessment does not account for two important ways that faculty homes differ from homes in Palo Alto.

The lawsuit argues that first, the University restricts faculty sales, ownership and use of these properties, and second, faculty homes are on ground leases. This means that while faculty may own the home, Stanford owns the land. Campus homeowners do not own the full property interest in these homes, and because of these arrangements with the homeowners, the University argues in its lawsuit that college interest is exempt.

“It’s important to emphasize that to live near work and foster the residential nature of this campus, Stanford faculty buy houses that are tied up in ways that other, external purchasers might not encounter,” Treharne wrote. “This is the original academic mission of the university: to be able to have colleagues living near their place of work to enhance the intellectual life of Stanford and its students.”