The Hoover Institution’s China’s Global Sharp Power Project hosted a discussion on the importance of promoting a sense of belonging for Chinese-Americans on Tuesday inside Hauck Auditorium. The panel, titled “A Fresh Start: Safeguarding People, Rights, and Research Amid US-China Competition” brought attention to the worries Chinese academics have over being profiled for espionage or fraud-related charges regarding possible affiliations with China’s government.

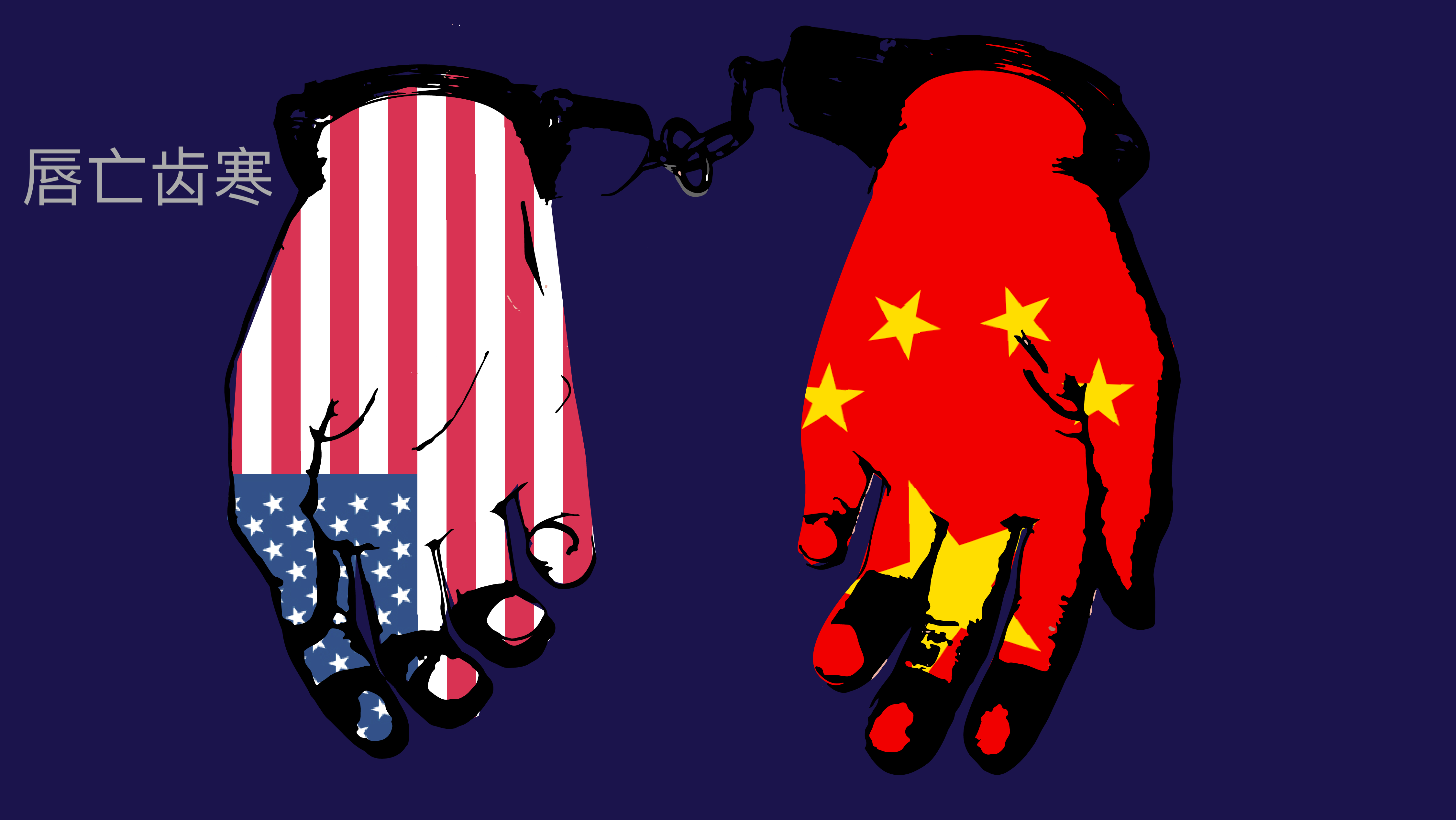

This animosity between the U.S. and China has a long history. When Communist Party leader Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the U.S. supported the exiled Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek, increasing friction between the two countries. In recent times, China has become a global superpower, capturing the attention of foreign governments. Escalating tensions over trade, disputed territories and indictments of Chinese nationals have dominated U.S.-China relations.

Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, moderated the panel with Gisela Perez Kusukawa, founding executive director of the Asian American Scholar Forum, Ambassador Gary Locke, former U.S. Ambassador to China (2011-2014), and Glenn Tiffert, research fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Locke, who is also the chair of the non-profit Committee of 100, opened the event by acknowledging the rivalry between the two nations across various industries. He highlighted the “need to understand that our dispute and contention with Beijing is with the government of China and not the people of China, and certainly not Chinese Americans.” Locke said [they] believe the contributions of Chinese Americans often go unnoticed, a further reflection of the invisibilizing of Asian Americans.

Kusukawa added that the treatment of Chinese-American academics is part of a broader historical pattern of anti-Asian rhetoric in America, resulting in the scapegoating of Asian Americans when the U.S. experiences tensions with an Asian country.

According to Locke, there needs to be clearer, consistent standards across federal funding agencies. He also pointed out that a survey from the University of Arizona in partnership with the Committee of 100 found that Chinese or Chinese-American scientists and professors were 5 times more likely to feel like they were being racially profiled compared to those who did not identify as Chinese.

“Since 1985, it has been U.S. policy that basic and applied research in science and engineering is basically unrestricted by the government,” Locke said.

Tiffert explained that this has led to a lack of oversight that resulted in compliance risks, failures and abuses across universities. Institutions were not aware of the ties between research conducted on their campuses and the Chinese government.

According to Tiffert, there was a significant shift when panic ensued with views that, “the Chinese government was asymmetrically exploiting the openness of our research enterprise to exfiltrate our technology, data and events, values and interests that were in conflict with our own.” Tiffert said the larger problem is an “issue with institutional due process and labor relations that manifests in the handling of a lot of controversies within academia.”

Much of the racial profiling Locke referred to can be seen in the China Initiative that was launched by the Department of Justice, according to Kusakawa. The initiative was intended to “protect US laboratories and businesses from espionage,” according to the journal Nature, but many academics and civil liberties groups claimed that the program was biased against researchers of Chinese descent. Chinese-American scholars and scientists were falsely implicated during the Trump-era initiative, reporting disastrous effects on their personal livelihoods because of the profiling. The initiative was terminated in February of last year after outcry was raised over how the initiative’s rhetoric further encouraged Sinophobic sentiment.

If we are to recognize the existing anti-Asian bias in America, “we need to start thinking [about] what are the due processes in place to protect Asian-Americans” Kusakawa said.

Kusakawa acknowledged the difficulties a university or faculty member faces when critiquing or challenging policies that reflect a power imbalance between federal agencies and those in academia. She encouraged making the process of filing a complaint or reporting racial bias a less intimidating experience and focusing on creating a better environment for foreign scholars.

“I think most people forget that our refugee and asylum legal system in the United States came into existence because we wanted to honor our American values,” she said. She further questioned the irony of targeting Chinese-American researchers during rising tensions with China over economic and industry rivalries.

“If we change how we approach research, are we genuinely going to become more competitive?” Kusakawa said. “We don’t think that Asian-Americans and Chinese-Americans and immigrants should continue to be collateral damage as we try to fix our policies in our country in addressing U.S. China relationships.”