With words of sacred scripture

I shield the oranges from the sting of phosphorous

and the shades of cloud from the smog.

I grant you refuge in knowing

that the dust will clear,

and they who fell in love and died together

will one day laugh.

—Hiba Abu Nada (1991-2023)

Translated from Arabic by Huda Fakhreddine

In 2021, the Palestinian American poet, translator and doctor Fady Joudah wrote: “I’ve long been aware of the crushing weight that reduces Palestine in English to a product with limited features, a perverse irony that revolves around the violence that Israel and the United States, culture and system, launch against Palestinians.” And later: “The overlap zone with Palestine in Arabic is not small, but the empathy field in English is malnourished.” These weeks we have witnessed the starkest reminders of this devastating lack.

In the United States, mainstream journalists use their English to obfuscate Israel’s crimes against a besieged civilian population in Palestine. Their English cloaks the perpetrators, making them invisible to every logic that would damn them. They suggest that Palestinians “die” while Israelis “are killed” and treat the occupied as terroristic and the occupier as reasonable and just.

The atrocities of Oct. 7 are repeatedly framed in the context of hundreds of years of antisemitism. But Palestinians are not granted this historical view. Instead, people are chastised or worse when they mention the last 75 years of Israeli occupation or when they condemn U.S. support of the slaughter of Palestinians.

Israeli officials wage war against “human animals” and “children of darkness,” familiar tropes meant to dehumanize. This genocidal language has gone largely unchecked by so many of our celebrated cultural and educational institutions. Rhetoric that should be met with denunciation and disavowal has instead been received with a cruel, festering, permissive silence — a silence that pledges its allegiance to one life and its disregard of another.

It feels absurd to write to you of language when hour by hour the people of Palestine face annihilation. But here we are, bereft of the widespread condemnation of these unambiguous horrors. Where is the fire-language of protection for our Palestinian, Muslim and Arab beloveds with whom we are in community? Where are the greennesses and blessings for the ones who speak, who fight?

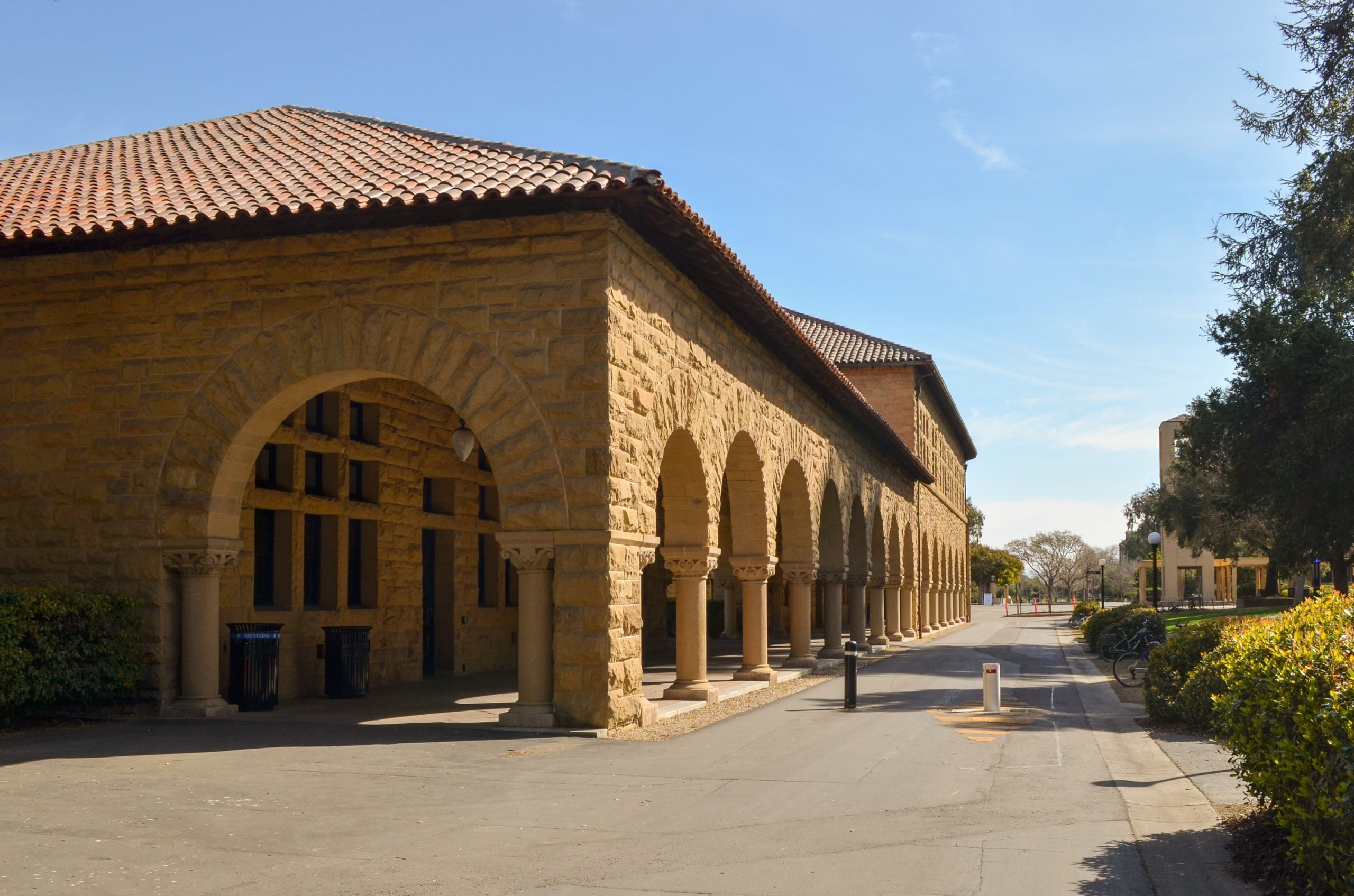

For me, the ongoing student sit-in at Stanford is a language unto itself, a collaborative practice that makes visible a presence of resistance, education and outrage in the face of such silence. These brave students of conscience have sacrificed their comfort in order to call us into dialogue at a time when so many are afraid to speak. It seems theirs is a vision of effortful togetherness, a patchwork of tents, tables and resources — an evolving grammar of grappling and disruption.

The words of poet Rasha Abdulhadi fly through me: “Let the soft animal of your body get in the way of the death machines. Let the soft animal of your body make some safety for other people. Let the soft animal of your body refuse and disobey.”

Protesters are rejecting the lie that all of our histories are unrelated and that this particular history is too complex to speak about if you support Palestinian rights and are not from the region. As Gwendolyn Brooks says, “We are each other’s business. We are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

On this campus, I consider what the sit-in might mean to a range of students, staff and faculty who are themselves survivors of ethnic cleansing or genocide. While these histories of catastrophe are distinct, they also exist within an intricate web of relation. I am seized by the possibility that this sit-in, in addition to making clear students’ demands, also generates a signal of commitment to our shared humanity.

***

The Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada — all blessings and wildflowers to her name — was killed by an Israeli airstrike within days of writing the poem excerpted in the epigraph above. With these words, in the last days of her life, she protects the oranges and the shades of the clouds. Elsewhere, she blesses the children. She writes a future when even the dead will one day laugh, and with her language makes a refuge, a refusal and a shield. These are the words I think of when I meet the students in White Plaza or see their tents from a distance as I walk to meetings.

These weeks we have seen student protesters refusing the regimes of silence that threaten to normalize mass killings. With their discipline, they shield action from despair. They are a greenness in the heart of campus, calling us to life.

Aracelis Girmay is a poet and professor of English.