Students took what they could get in the 1950s at Stanford. “This was not a time in which people raised big questions about what they were being taught,” history and humanities professor emeritus James Sheehan ’58 said in an interview with The Daily. “And that’s no longer true, which is a good thing, actually.”

Back then and still today, effectively every American college instated some form of general education requirements to receive accreditation from the U.S. Department of Education or the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, though curricula have undergone continual evolution.

Stanford, which is accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, currently implements a set of breadth requirements collectively known as Ways of Thinking/Ways of Doing. The Ways system, as it is known, traces back to the Study of Undergraduate Education at Stanford University (SUES), which began in 2010 and whose results were published in a foundational report in 2012, two years before the implementation of the system.

At the time, undergraduate students devoted about 25% of their total units at Stanford to requirements outside their majors, according to the report.

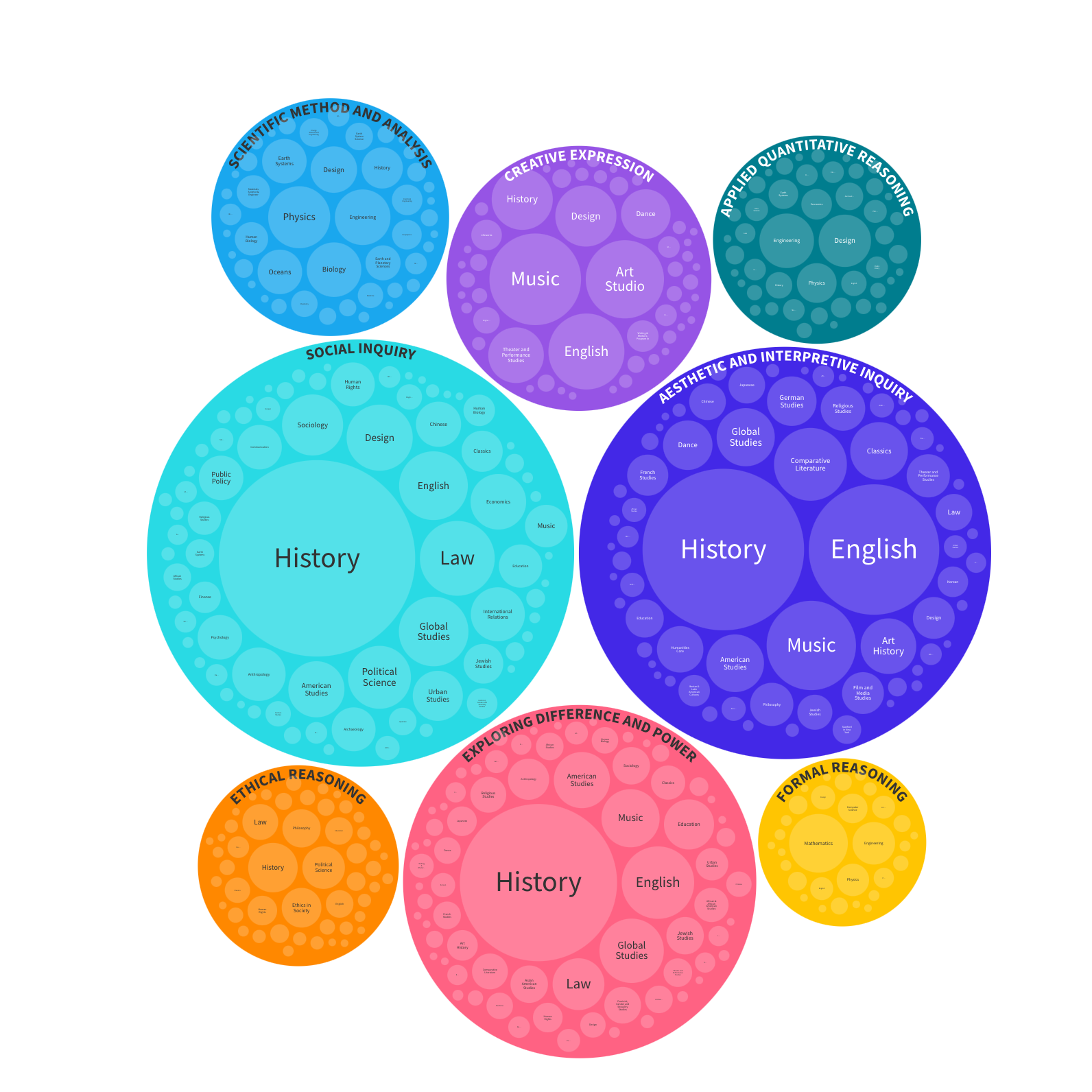

For the 2023–24 academic year, more than a decade later, the Department of History offers the most Ways (220), followed by the Departments of Music (144) and English (115), The Daily found in an analysis of listings on ExploreCourses.

The SUES report and its downstream effects were somewhat the latest iteration of several initiatives aimed at enhancing the educational experience through academic policy changes, including the Study of Education at Stanford in 1968 and the Commission on Undergraduate Education (CUE) in 1994, the latter of which Sheehan chaired.

“If you look at the history of this common core, what you find is that each answer to the question has a shorter life,” Sheehan said, referring to Stanford’s Western Civilization requirement, which started in 1923, ended in the 1960s and was followed by a requirement called Cultures, Ideas and Values (CIV), which lasted for less than a decade. The most recent predecessor to Ways was developed in the early 2000s and lasted until 2014.

Today, across the School of Humanities and Sciences, an average of 23.6 Ways-eligible courses are listed per department, and the median is 17.0. As the disparity between the mean and median suggests, these data have substantial spread. The standard deviation over departments is about 27.5.

Across the Doerr School of Sustainability, an average of 17.4 Ways-eligible courses are listed per department, and the median is 11.0. The standard deviation is approximately 15.4.

The School of Engineering has an average of 12.4 Ways-eligible courses listed per department, with a median of 9.0 and standard deviation of approximately 9.11.

Within individual departments, the different kinds of Ways credits offered can widely vary. All 46 Ways-approved courses in the Department of Mathematics exclusively satisfy Formal Reasoning, for example.

Upon learning from a classmate early on that the Department of Classics offered many courses with a mixture of various Ways, Emily Dickey ’23 M.S. ’25 decided to pursue the classics minor, and she said that it turned out to complement her studies as a major in mathematics.

When Dickey took CLASSICS 16N: “Sappho: Erotic Poetess of Lesbos,” an Introductory Seminar, it counted toward Engaging Diversity, a Ways requirement that has since been renamed to Exploring Difference and Power (EDP). EDP is listed for some courses in history, anthropology and feminist, gender, and sexuality studies among many other programs.

“Maybe I would not have been a classics minor had I not taken that class and really enjoyed it and met people,” she said. “I didn’t have to jump through that many hoops … I was able to get a lot of the requirements done in a meaningful way,” she said of her classics minor.

Whereas the predecessor to Ways defined breadth in terms of disciplines, breadth requirements are now defined in terms of sets of intellectual capacities:

- Aesthetic and Interpretive Inquiry (AII)

- Applied Quantitative Reasoning (AQR)

- Creative Expression (CE)

- Exploring Difference and Power (EDP)

- Ethical Reasoning (ER)

- Formal Reasoning (FR)

- Scientific Method and Analysis (SMA)

- Social Inquiry (SI)

In the system preceding the Ways system, named Disciplinary Breadth, students had to take at least one course in each of the five broad areas designated as Engineering and Applied Sciences, Humanities, Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences.

Additionally, students were required to fulfill Education for Citizenship, which breaks down into four subareas: Ethical Reasoning, American Cultures, Global Community and Gender Studies. Even though Education for Citizenship comprised four subareas, students only had to take two courses selected from any of the four. The SUES committee wrote in its report that it is “absurd on its face” to suggest that selecting two courses from four possible categories would equip students for meaningful citizenship.

Starting in 2005, nine years before Ways would take effect, Stanford used an “opt-out” approach, “presuming that courses fulfill their most logically related Disciplinary Breadth requirements unless instructors say otherwise.” Prior to Ways, students could also stack breadth requirements offered by a course, simultaneously receiving credit for multiple ones in some cases. In the current system, students can only count one Ways requirement from a completed course, even if it is listed with more than one.

Over the course of soliciting perspectives from the community in the early 2010s, the SUES committee found, with few exceptions, that the students to whom they spoke “described approaching their general education requirements in a purely instrumental way.”

Many students likewise reported cross-referencing ExploreCourses with CourseRank to find the intersection at which courses fulfill the most requirements while awarding A grades to the greatest percentage of enrolled students, according to the report.

“It is characteristic of faculty, on hearing all this, to condemn students for their cynicism, but the fault is more ours than theirs,” the report subsequently read. “If students conceive intellectual breadth as a series of ‘hoops’ or ‘tick boxes,’ it is because we have presented it in that way.”

John Etchemendy and John Bravman ’79 M.S. ’81 Ph.D. ’85, Provost and Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education at the time, respectively, initially charged the 15-person committee behind SUES with assessing the student experience of Stanford’s curriculum and presenting practical recommendations for keeping, removing or revising undergraduate requirements.

After SUES first proposed Ways, the Committee on Undergraduate Standards and Policies (C-USP) deliberated over the prospective system and wrote the legislation that would eventually be passed in the Faculty Senate, according to Senior Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education Sharon Palmer ’90.

The upshot is that undergraduate students need to take at least two courses for each of AII, SI and SMA, as well as at least one course for AQR, CE, EDP, ER and FR.

“Obviously, there would be faculty arguing passionately for the need for more courses in each of the other Ways categories as well, but the 11 course total represents a negotiated balance … not only for major and general education requirements but also for free exploration,” she wrote in a statement to The Daily.

The University body responsible for fielding and granting instructors’ Ways requests is the Breadth Governance Board (BGB), according to Dan Edelstein, professor of French and formerly a member of the BGB (2013–17). During his time on the BGB, Edelstein noticed that many students, particularly those studying STEM fields, tended to put off fulfilling the more humanistic Ways requirements until senior year.

“That’s unfortunate, because I think that’s kind of like doing it backwards,” he said of what he noticed. “It can be really beneficial before you go into your major to have explored a bit more, to have learned a little bit more about different disciplines and different fields, and it may be that that knowledge will give you a different insight into your own field.”

The BGB reports to C-USP every year and the Faculty Senate every four years. While the BGB works closely with Institutional Research and Decision Support to assess metrics on Ways, the requirements are “so flexible and students take a wide variety of courses to fulfill each Way,” making it “challenging to measure uniform learning outcomes apart from what students report about themselves,” Palmer wrote.

There is some likelihood that the Ways system will need to adapt in the years ahead as generative artificial intelligence (genAI) technology matures, and the scope of its impact becomes clearer, according to Hideo Mabuchi, BGB chair and applied physics professor. “It’s quite possible that the perceived utility of conventional coding skills will decline, and that those courses will evolve to incorporate significant use of genAI tools,” Mabuchi wrote.

“Some other areas might well emerge in the future as critical interests that could potentially be served by adding or replacing a Way – perhaps AI, or sustainability, or something else– or be otherwise woven into the undergraduate curriculum and its requirements.”

“Most Stanford classes are rigorous in some level to probably warrant a Ways requirement, right?” Dickey said, adding that “it just feels arbitrary,” at times, which courses are designated as eligible. “If you wanted people to genuinely explore, and to have a lot of agency over that and not feel pigeonholed, you would have basically all classes counted for the Ways that they are.”

Today, the process of making a course eligible for fulfilling Ways credit is initiated by the instructor of a course, according to Geoff Cox, senior associate dean for administration and finance in the School of Education.

His offering of EDUC 204: “Introduction to Philosophy of Education” fulfilled no Ways requirements as recently as the 2021–22 academic year, according to ExploreCourses. Then Cox submitted a BGB request explaining his reasons why he believed his course could be listed with the ER and SI requirements. Before the course was approved for Ways, somewhere between 20 and 25 students enrolled. After it was approved for Ways, though, that number rose to about 60.

“It is not so much a problem. It’s just a very different course,” Cox said. “There’s a big difference between teaching 20 and teaching 60 … some courses work better as small classes.”

Dickey said that it might not be rewarding or as enjoyable for professors to teach Ways-eligible courses, because such eligibility could lead to a class consisting of comparatively more students who are there “just trying to check a box,” but still, “it would be nice if every class was actively categorized, or there was some petition mechanism.”

Ways requirements were “not a big deal” for Brooke Seay ’23 M.S. ’25, who majored in human biology and minored in creative writing. “It wasn’t like math, where everything is Formal Reasoning.”

“The philosophy of my major was aligned so strongly with the breadth and Ways of Thinking,” she said, citing the role of social context in understanding biology, as well as the necessity for strong scientific writing skills and a command of statistics. “I think Ethical Reasoning was the only one that I had to, like, seek out.”

She eventually found and enrolled in HUMBIO 174A: “Ethics in a Human Life,” an upper-division human biology course that worked with her schedule and fulfilled the requirement, which turned out to be one of her favorite classes.

ER is currently the most scarce Ways credit, per The Daily’s analysis of listings on ExploreCourses. However, with the guidance of the universal first-year requirement of the Civic, Liberal, and Global Education (COLLEGE) sequence, students may take “Citizenship in the 21st Century,” which satisfies ER, according to Edelstein, who has taught the course multiple times.

“As an institution, maybe we need to find other ways to incentivize students to take classes outside of their comfort zone,” Edelstein said. “I think students who are pre-med or engineering tracks, where there are a lot of prerequisites, often feel like they have to do all the prerequisites first … It’s kind of an organizational problem,” he said, adding that a possible solution might involve adjusting when certain classes are offered and easing potential sources of burden.

Balancing an aspirational model of liberal arts with practical details is not a new challenge to Stanford. It was in the 1960s when the Western Civilization requirement began to fragment, said Sheehan, who taught at Northwestern University before joining the faculty at Stanford. “It became impossible really to keep this common experience together, and so it began to break up into a variety of ways to approach the same topic.”

Stanford does differ from many schools in that it has the same general education requirements for all undergraduate students, Sheehan said, citing departments housed in Northwestern’s Technological Institute, for instance, whose undergraduates have their own set of general requirements, he said.

Sheehan added that over the years universities have become “extremely complicated” with larger administrative staff and larger budgets and “increasingly difficult to run,” yet universities continue to hold a unique position in society.

“People don’t come here from other countries to ride our public transportation system. They do come in great numbers to study at our universities, which is a sign, I think, of their enormous success,” Sheehan said. And he said that the purpose of a university is what separates it from other institutions, and the failure to explicitly articulate said purpose “creates a vacuum.”

“Vastly different major requirements” are a persistent challenge in establishing a common basis for meaningful undergraduate experience, Sheehan said, especially when further expectations must be incorporated, such as discipline-specific standards set by the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology.

“This sets real limits to what can be done,” Sheehan said. “At the same time, I would hate to think we would give the whole thing up. I think it’s worth genuinely trying to ask ourselves what it is our students should learn and what they need.”