“Counterpoints” explores the diverse intersections between music and other disciplines, from technology and AI, to medicine, sports and the arts. Through conversations with individuals and features on projects and events across Stanford’s campus, Feng explores how music fuses with unexpected fields to create new forms of expression and innovation.

A year ago, I was glaring down at my computer at two in the morning, wondering how on Earth I was going to determine the most significant challenge society faced within Stanford’s 50 word limit.

Essentially, the question was asking what keeps us up in the middle of the night — other than college applications, of course. As a lifelong pianist, there was only one way I could answer: artificial intelligence’s destruction of artistry. We live in a world where AI composition software and computer-mediated instrumentalists threaten to replace original creators. The human touch and meaning we crave in art are gradually ceasing to exist.

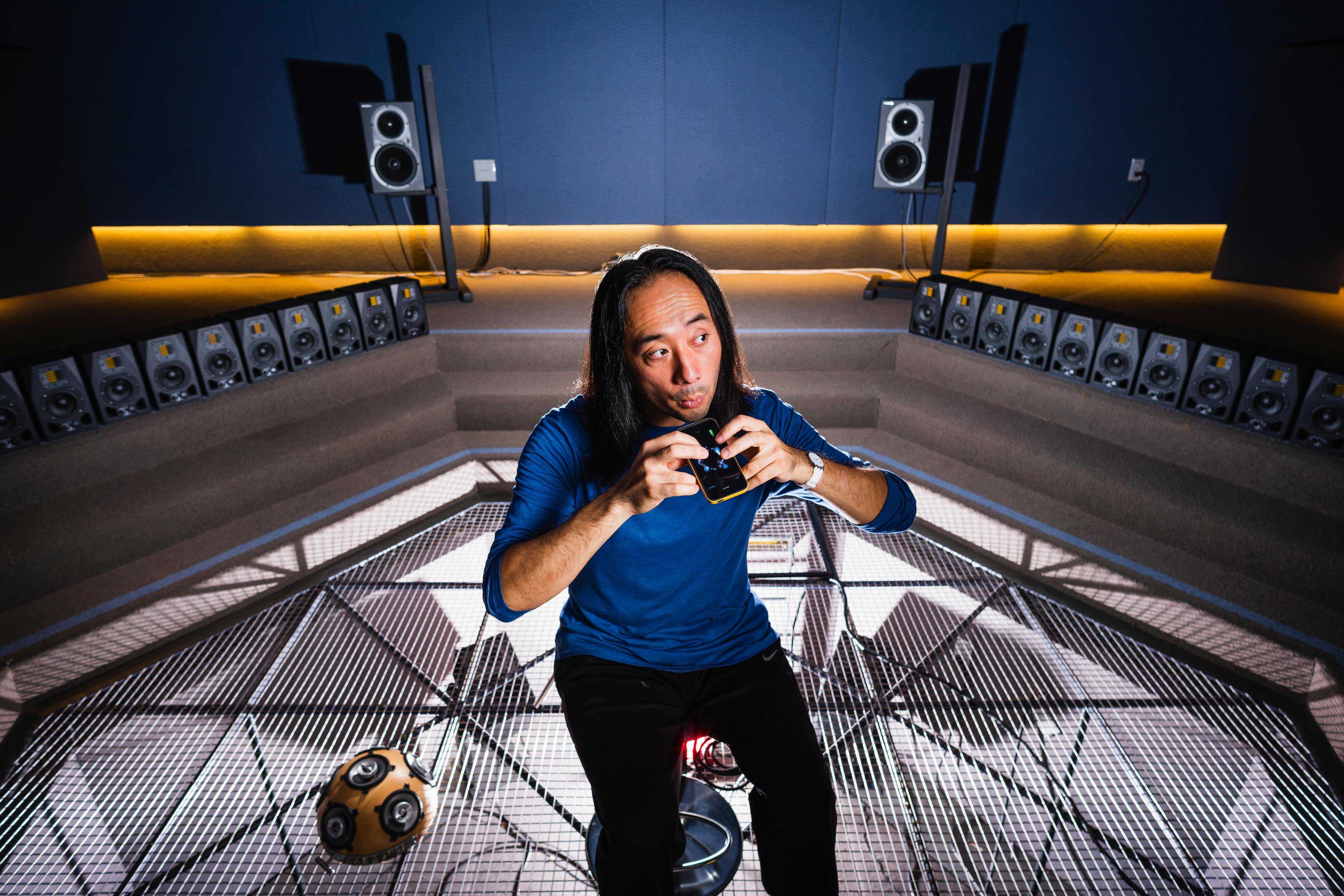

Ge Wang, associate professor of music, senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence and associate professor of computer science, offered a compelling perspective on what it means to create in a technological world.

“It’s too automatic to think that the role of technology is to make everything easier,” Wang said. “What makes life interesting are the hard things.”

In his article “Gen AI: Art’s Least Imaginative Use of AI Manageable,” he made an analogy between mountain climbing and creating art. As a backpacker, Wang knows that the process is everything. “All things worthwhile are mountains to climb. The arduous path is the only path.”

Art, too, is more process than result. The more you play the piano, the more you discover yourself. In that sense, technology shouldn’t skip the hard steps, but give us more meaningful work to do. According to Wang, the tools we build shouldn’t be just for the sake of labor-saving. He said there are kinds of “virtuous labor” that are vital to undertake, like knowing what it means to “suffer for your art.”

Stanford music students echoed this idea of grounding innovation with tradition. As Anliese Bancroft ’25 put it: “When used well, technology can help us express emotion; I see people in Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) use AI only as a tool to enhance humanity; however, we have to return to musical foundations like old manuscripts, composers, counterpoint and voice to understand why things resonate.”

So technology shouldn’t remove the difficulty of climbing the mountain. But what if it made us want to climb it? CCRMA, where Wang teaches, is where this technology is realized. His programming language, ChucK, allows his students to learn to write code, work with sound and build instruments, as seen in his work with the Stanford Laptop Orchestra.

“Building tools shouldn’t be about making things easier,” Wang said. “A good tool asks something of you — time, practice, patience — with the faith that what you get out of it doesn’t come from the tool itself, but from you.”

In every way, it’s like a musician’s relation to their instrument. The instrument itself doesn’t move you or the audience. It’s the relationship you’ve built through years of practice. Every note carries the artist’s effort, their family’s support and the memories that make up our music.

In a way, the piano is a technology, but it’s a technology that demands something of you. You have to put in the time. Anyone can ask AI to generate piano music. “But it’s not the same; it doesn’t have you, your history or your memories,” Wang said.

Musicians who grew up immersed in both classical training and digital tools see this divide; as Stanford Philharmonia pianist Tom Liu ’29 said, “AI has the potential to fix many inefficiencies in piano learning so we can focus on the humanistic parts. However, the goal of music is also to communicate. AI can harmonize, but we must create the melody”.

What Wang emphasized is the importance of the moment when you’re finally on the top of the mountain (or for a musician, on stage). After months, years of work, you’re no longer thinking about the technical elements, but how to express the phrase and the meaning of each measure. Wang said, “your body becomes a translator for emotion. The world falls away. That’s the sublime, something that makes us still. It’s that contemplative moment where you can look back on the journey, how difficult it was, and ask yourself, why does this feel so good? Because I made this. I created this.”

Wang has recently begun a new endeavor: writing a “hidden design book” about education and the “sublime” in life. It all started with his grandmother, whom he grew up with in Beijing. He reminisced about her zhajiangmian, a traditional Chinese black-bean noodle dish. “When my grandmother made me zhajiangmian, it wasn’t just food. It was love, memory and family, encoded in every bowl. When I eat those noodles, I taste my entire history. That’s the feeling — the sublime — that I’m chasing in my work.”

In his search for humanness in an ever evolving world, Wang reminisced on how his grandmother guided him as a mentor. “She was the greatest teacher.” She didn’t just try to get me to the answer, Wang described, “she gave me the tools to find answers myself.” Wang said he believes being your authentic self “is the act of rebellion”. He said his grandmother, who lived to 103 and endured hardships from poverty to political upheaval, was the best sleeper — nothing kept her up at night. She would say, “you gotta learn to cry with the world, and you also gotta learn to laugh with it.”

So despite society’s many issues keeping us up at night, that’s how Wang learned how to fall asleep: by holding on to the authenticity of himself. The tension and crisis remain, but that’s the work. What Wang hopes is to build tools that help people become more themselves. So, the journey continues. Wang described CCRMA as the “rebel alliance”: A hub of resistance making room for everyone and everything, including AI in music, without letting it dictate anyone.

As Wang said, “It’s only when you stop thinking about what everything is for when you begin to live free.”