In the time it takes to blink, octopus and cuttlefish can seemingly disappear into their underwater environment by changing both the color and texture of their skin. Replicating these dual camouflage tactics in synthetic materials, however, has long stumped engineers.

Stanford researchers have begun to crack the code, developing a programmable polymer film that can rapidly swell into different colors and textures. Led by members of the Geballe Laboratory for Advanced Materials, the team published its findings in Nature on Jan. 7, describing the cuttlefish-inspired “photonic skin” and its potential to reshape approaches to camouflage, robotics and display technology.

“Nature has so many incredible sneaky things that it does that you would not anticipate until you look closely,” said Nicholas Melosh, a professor of materials science and engineering and senior author of the paper.

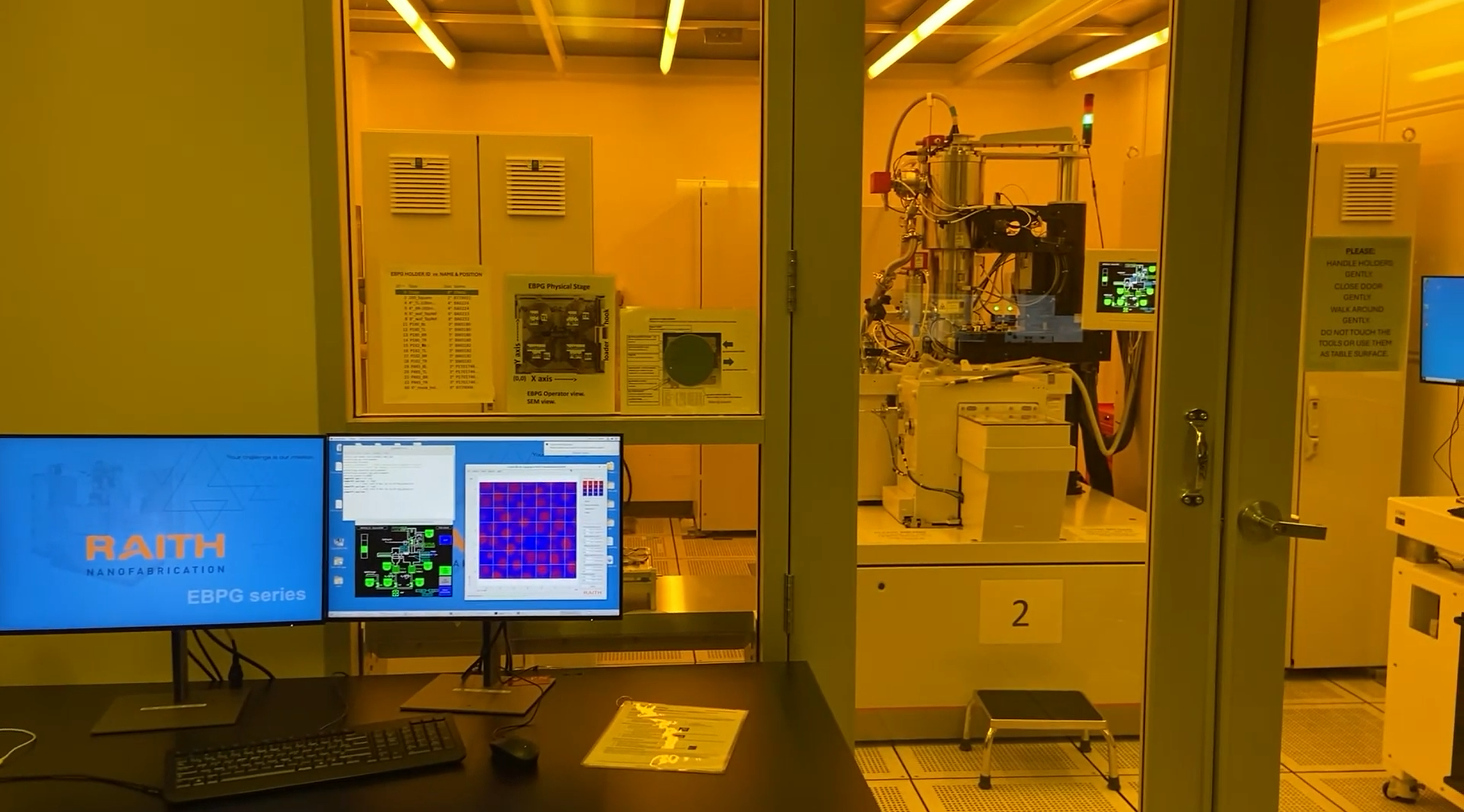

To create films with controllable texture, the researchers used electron beam lithography, firing beams of electrons at the polymer PEDOT:PSS to encode patterns and dictate its swelling behavior. When placed in water, the polymer swells into the programmed topography, forming features such as bumps and waves; in isopropyl alcohol, the polymer flattens back to its original state, making the process fully reversible.

The team demonstrated the film’s capacity for complexity by creating a replica of Yosemite’s El Capitan rock formation. Patterns can also be encoded at the micrometer scale to control surface finishes like gloss and matte — properties of visual appearance the researchers describe as “underexplored” and ones that cuttlefish naturally exploit.

Thus, using the polymer film in computer displays could enable the displays to appear more “lifelike” by adding dynamic surface features alongside color, according to lead author Siddharth Doshi, a postdoc at Caltech who was a sixth-year Ph.D. student in materials science at the time of publication.

The programmable surface was an unexpected discovery, Doshi said. While working on an earlier project, he chose not to discard an old PEDOT:PSS polymer sample that had been exposed to the electron beams of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Instead, he observed the polymer as it swelled, noticing regions of defects caused by electron exposure. It wasn’t until a nudge by a mentor and a few early, “janky” experiments that Doshi turned to electron beam lithography for precise patterning of the polymer.

The researchers also leveraged the polymer’s swelling behavior for dynamic color control. They placed thin metal layers on both sides of the polymer so that as it swelled into its programmed topography, the distance between these two mirror-like layers varied. Depending on the spacing, the mirrors would reflect different wavelengths of light, producing specific color patterns across the film. Once water is applied to the polymer, 90% of the color change occurs in less than 10 seconds.

Colors can be further tuned by applying a specific mixture of alcohol and water to the polymer, accessing the intermediate color combinations encoded between the polymer’s fully swollen and de-swollen states.

“We can actually cover a decent range of colors,” Doshi said. “But to get a really precise shade of green and then get a certain darkness or brightness or intensity or saturation of color, that is still pretty hard with our system.”

Simultaneous and independent control of color and texture can then be achieved through a bilayer device, where one side of a piece of glass or plastic contains a polymer film for texture control and the other side a film for color control. The device can exhibit both color and texture, texture-only, color-only or neither.

Now that he has developed the physical skin, Doshi is focused on figuring out how to best control it.

“The cuttlefish, for example, is able to achieve all this nice camouflage and create these complex appearances not just because of its skin but also because it has a very interesting brain and an interesting nervous system,” Doshi said.

Each cell of a cuttlefish’s skin is controlled by a neuron, and synthetically replicating whole cuttlefish-like patterns would require precise control of thousands of pixels, Melosh said. To address this challenge, the researchers are now exploring “naturalistic” neural interfaces to control individual pixels without the need for thousands of wires.

According to Melosh, the polymer film also has potential in displays for wearable devices – for example, small and flexible skin patches that can measure pulse or blood oxygen levels. The material’s flexibility and stability in water could also make it suitable for use on tiny lenses inserted into veins or intestines for disease detection.

“One of the fun things about doing these kinds of projects is just seeing the diversity and clever solutions that nature has come up with and then being able to try to replicate some of those ourselves,” Melosh said. “And then we’ll see where they go after that.”