One of the most exciting and avant-garde events at this year’s San Francisco International Film Festival was the live documentary presentation of director Sam Green’s “The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller.” It screened twice at the SFMOMA on May 1, a presentation facilitated in tandem with the SFMOMA, which has a current exhibit on Buckminster Fuller in the Bay Area.

Sam Green provided live voice-over commentary for the film, and indie rock band Yo La Tengo performed the film’s score live. In this setting, the film became a hybrid of cinema and theatre and the images on screen more like a visual aid to a live performance than a stand-alone piece.

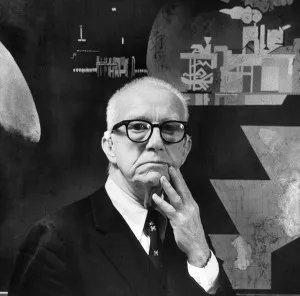

Buckminster Fuller was the quintessential Renaissance man: a designer, thinker, architect, innovator, writer and lecturer decades ahead of his time. Although perhaps most widely known for his thick, black glasses and geodesic domes, Fuller’s legacy extends far beyond that. He was a strong proponent of big-picture thinking and was, in many ways, a champion of design thinking. Although some of his ideas can be easily dismissed as far-fetched, the point wasn’t always to build everything he proposed but to expand people’s horizons about how they think about the world and making things work.

As we learn through the film, Fuller kept an archive of all of his activities — including every receipt, every memo and every television appearance — in what is now known as the Dymaxion Chronofile. It is the most extensive archive of any single person’s activities, owned and housed by Stanford University’s libraries, and was the primary source material for the film and the exhibit. There are excerpts in the film showing Buckminster Fuller meeting the hippies on Hippie Hill in Golden Gate Park, as well as some of his television appearances. The film is essentially a montage of photographs and archival footage of Fuller and his work, with a few present-day interviews with scholars of the Chronofile.

The difficulty with both the SFMOMA exhibit and Green’s film is that, by choosing to focus on Fuller in the Bay Area, they have also chosen to ignore the greater context of his work. In fact, Green did not interview anyone for his documentary who actually knew or worked with Fuller personally, despite the fact that many of them are still alive and active. Without this context, it becomes far too easy to dismiss him and some of his far-fetched ideas as the products of a crackpot rather than an innovator trying to challenge the status quo.

For example, the World Games workshops Fuller ran — where motivated people came together to hear him speak, get inspired and work to solve the world’s biggest problems from food security to sustainable development — weren’t in the Bay Area, and thus they are altogether ignored in the film. Because Fuller’s concept of “Spaceship Earth,” a place that we all have to share with limited resources that we need to preserve, was not a Bay Area specific idea, it too is ignored. Yet these are two of Fuller’s key legacies and proof that he was a leading-edge thinker.

The reference to T.S. Eliot’s “Love Song for J. Alfred Prufrock”, a poem about a lovable but pathetic man, in the film’s title is no coincidence. It’s sadly an apt metaphor for Green’s view of Fuller: affectionate, but somewhat unimpressed. Perhaps the film would have done better to draw its inspiration from the Beatles’ song “Fool on the Hill,” in what could have been a much less ignorantly critical ode to Fuller without ignoring his