Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s “The Stanford Prison Experiment,” screening in the US Dramatic Competition at the Sundance Film Festival, recreates Dr. Philip Zimbardo’s landmark 1971 experiment with painstaking detail. Student volunteers were divided into two groups and assigned roles as prisoners and guards and then stationed in the basement of Stanford’s Jordan Hall for six days. It’s a harrowing thing to behold. The guards, seemingly normal young students, become vicious, cruel and brutal. The researchers cross ethical lines, becoming complicit in the abuse by never interfering, even as the guards violate the volunteer contract by physically harming the prisoners. But it’s a shame that the film has such tunnel vision about the excruciating days during which the experiment took place and never looks beyond to see what the long-term ramifications of the experiment were.

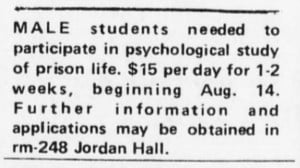

The film opens on an ad, seeking undergraduate male study participants, being devised and then printed for the eponymous experiment — presumably in this publication, The Stanford Daily. We then see scores of volunteers getting screened by Dr. Philip Zimbardo (Billy Crudup, whose character I’ll call “Phil”) and his team of graduate student researchers (including James Wolk and Gaius Charles). The young men who participate as subjects in the experiment are a parade of who’s who of talented, up-and-coming actors — from Ezra Miller (“We Need to Talk About Kevin”) to Miles Heizer (“Parenthood”) to Tye Sheridan (“Mud”) to Michael Angarano (“The Knick”). They’re asked questions to determine their emotional stability.

A coin toss will determine whether a given participant will be a prisoner or a guard. And so it begins. Prisoners are rounded up from their homes by cops, sent to the “Stanford Prison,” forced to strip and put on a prisoner’s uniform — effectively a rag dress and a hat made of pantyhose, intended to feminize them as a form of humiliation. There are nine prisoners, and the guards rotate shifts, with three of them at a time. They’re dressed in uniforms with sunglasses, designed to turn them into a united front.

At first, things are calm and the boys are hesitant. They’re giggling and actively playing the roles they’ve been assigned, assuming this will be an easy way to win two weeks’ pay. But the guards are given free rein, and some of them, like Christopher Archer (a terrifying Michael Angarano) jump at the opportunity to exert their dominance and abuse their power. Their casual cruelty, which starts to violate the contract of the experiment, when they start to actually use their batons to physically harm the prisoners, incites rebellion, lead by Daniel Culp (a fascinating and mesmerizing Ezra Miller), or as he’s referred to throughout the experiment, Prisoner 8612.

The guards’ cruelty starts out with benign name-calling but quickly escalates to denying prisoners’ bathroom privileges, keeping the prisoners from sleeping, and physically and emotionally abusing them constantly. We see the horrifying pleasure some of the guards get from this, and the ways in which other, more restrained guards, like Marshall Lovett (Miles Heizer), don’t participate, but don’t stop or call out the bad behavior. Some prisoners respond with impeccable obedience, earning them rewards, while others refuse to accept the injustice and find themselves beaten, undressed and shoved into solitary confinement. At some point, it’s no longer an experiment, but an actual prison, where basic human rights are denied in a manner that would otherwise be illegal.

Within the first three days, there seems to have been enough psychological damage for a lifetime. By this point, we get the message: Putting people in a certain environment, with clearly defined and assigned roles, can fundamentally change their personalities. Seemingly normal people can become martinets, if given power, while others can become quivering, terrified shells of their former selves when subjected to abuse.

Those in power won’t necessarily question others in power, and the so-called prisoners won’t refuse to accept the abuse doled out, because the environment they’ve been put in signals that they don’t have this right. The film insists on showing us the experiment continuing to unfold as things escalate more and more, but nothing new gets added. It’s already made its point, and it’s on repeat.

Midway through the experiment, one of the graduate students (James Wolk) remarks that what they’re doing isn’t an experiment; it’s a simulation. And when one of Phil’s colleagues stumbles upon the experiment, he aptly asks what independent variable they’re using to test what influences behavior — apparently, Phil hadn’t even considered having one. If there’s anything scientific about what they’re doing, it’s not evident in the film, which mostly looks at the “experiment” as an act of cruelty.

Did they even have hypotheses? What were they testing? Was it really as vague as “What happens if we tell some people they’re prisoners and others that they’re guards?” It’s a wonder that the film won the Sundance Alfred P. Sloan prize for science-in-film, considering there wasn’t really any science in the film. Then again, this prize has gone to questionable sci-fi films in the past, like last year’s “I Origins”. Putting “experiment” in the title seems to have guaranteed them a win.

There’s a big missing piece in the film: What happened to these boys after the experiment? Two of them — who had been resisting authority the most and were thus the most brutally punished — are allowed to leave early “on parole,” because they’ve gone through mental breakdowns, and Phil fears they may take legal action to shut down his work. Meanwhile, the researchers stand idly by, continually wondering if they should interfere, but decide not to — some of them end up leaving before it ends, because they’ve sickened themselves too much with their complicity. Throughout the film, I kept thinking to myself that these boys are going to suffer from PTSD, that they’ll need years of therapy to cope with the trauma, and that even the graduate students running the experiment may have similar issues because of what they’ve allowed themselves to become through bearing witness.

Last week, I sat in on a panel discussion, with the real Dr. Phil Zimbardo, promoting documentarian Jennifer Siebel Newsom’s new film “The Mask You Live In,” about redefining masculinity in the 21st century. Zimbardo has now become a major advocate for making empathy and sensitivity socially acceptable qualities for men to publicly exhibit. Yet in “The Stanford Prison Experiment,” whenever a prisoner or a parent of a prisoner complains about his treatment, Phil always dismisses it with an appeal to their masculine identity: Aren’t you tough enough? He’s portrayed as a callous villain, incapable of empathizing with his subjects because he’s so caught up in the potential results. That this man could go from exploiting our unhealthy definition of masculinity in the ‘70s to working to actively change this social norm in the 2010s is pretty radical. But you’d never know what or how this change was sparked from the film. That could have made this a deeper, less repetitive film.

Many of my colleagues have been saying that “The Stanford Prison Experiment” would have worked better as a documentary, and there’s merit to this claim. We don’t need to see every form of abuse, each individual escalation, because what’s most interesting is not repeated close-ups of the prisoners reacting to what’s happened to them — even though the acting here is very good — but what the experiment’s long-term effects were. Why were some compliant and others rebellious? How did this affect what they took away from the experiment? Why were some guards casually cruel while others remained calm but didn’t stop any of the cruelty? How did they all cope with their actions afterward? Important psychological discoveries were made, but at what price? A documentary could have explored this, but a narrative film could have, too, had the film not been entirely stuck in the experiment itself.

By choosing to put us in these young men’s shoes, particularly the prisoners, feeling their suffering throughout the film, Alvarez has lost sight of the bigger picture. We know unimaginably bad things happened by the end first hour of the film, and seeing them continue to occur can only do so much. It’s short-sighted and limited, and while the film is certainly compelling and thought-provoking, it had the potential to do so much more.

Contact Alexandra Heeney at aheeney ‘at’ stanford.edu.