A hot stinking mess of science fiction plot machinations, “Chappie,” the latest dystopian feature from South African writer-director Neill Blomkamp, is a periodically entertaining yet woefully amateurish flick about the ever-increasing capacity of artificial intelligence. Devastated by a script that is simply too quick to condescend, “Chappie” sacrifices subtle and genuine character development for ham-fisted exposition. Fortunately, the film is bolstered by a truly remarkable Sharlto Copley — who, as the eponymous robot, actually manages to out-humanize each and every one of his mortal contemporaries — and an explosive finale, which sincerely rivals the splendor of Blomkamp’s Academy-Award-nominated “District 9.”

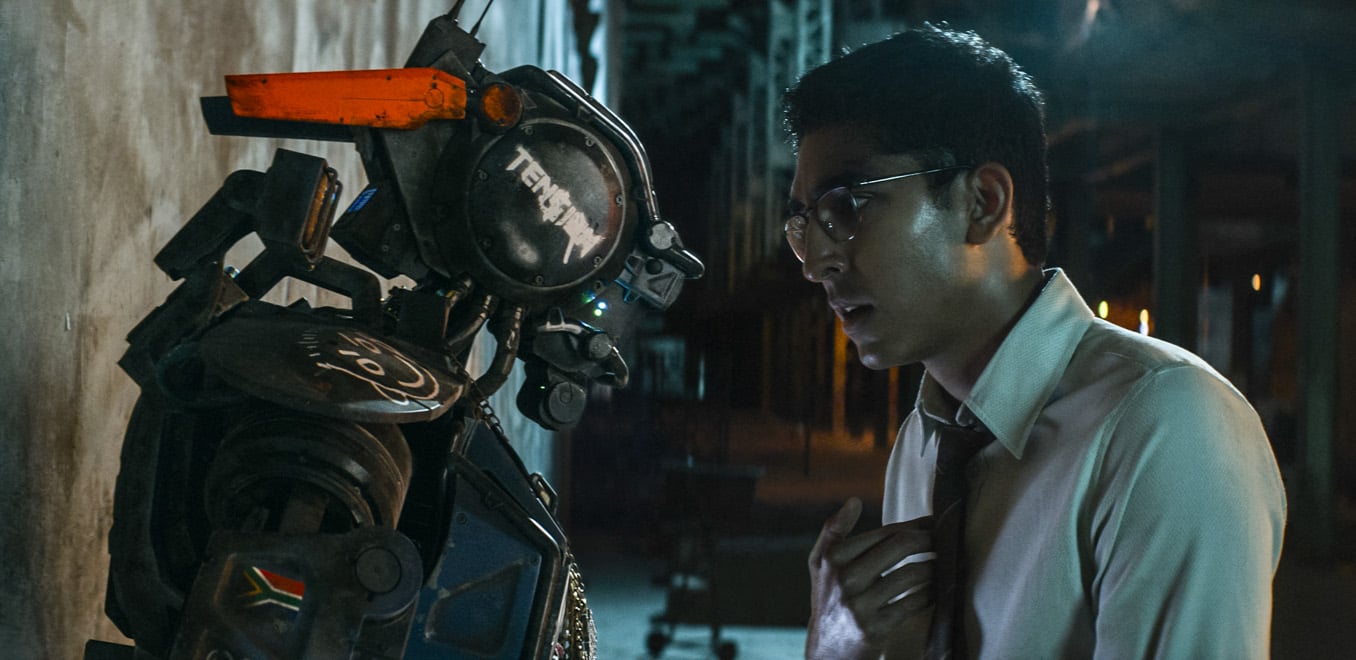

Set in Johannesburg, South Africa — Blomkamp’s hometown — “Chappie” begins with a series of faux telecasts trumpeting the arrival of a new breed of law enforcement. With urban crime repeatedly endangering our boys in blue, the government installs a legion of robotic sentries to protect Jo’burg from the brutal savagery of its occupants. Designed by ambitious engineer Deon Wilson (Dev Patel), these mechanical patrolmen quickly swing into action, easily disabling scores of violent criminals including felonious half-wits Yolandi (Yo-Landi Vi$$er) and Ninja (Ninja). Hoping to settle a rather hefty debt with a dread-locked wack-job named Hippo (Brandon Auret), Ninja and Yolandi hatch a plan to kidnap Deon and employ his programming prowess to shut off the astonishingly efficient Robocops. Unfortunately, Deon does not possess such managerial power, so instead the anxious boy “genius” offers his thuggish captors the answer to artificial sentience — a discovery, which he luckily happened upon mere minutes prior. And, with that, Chappie, our intrepid protagonist, is born.

Unfortunately, that’s only half the story: There’s also another, rather unnecessary, subplot featuring Hugh Jackman as one of Deon’s jerkface co-workers and something shallow and corporate involving Sigourney Weaver. “Chappie” is just teeming with narrative antics, yet the vast majority of these plot orchestrations are, in reality, fairly superfluous. There are four separate antagonists in this movie, but these villains all amount to little more than carbon copies of one another, magically summoned to say “no,” make the occasional threat and angrily point guns at poor Deon. Simply put, there is just too much going on in “Chappie.”

To make matters worse, Blomkamp attempts to remedy this narrative convolutedness by dumbing everything down for maximum comprehension. About every other line in this half-baked script — penned by Blomkamp and frequent collaborator Terri Tatchell — is straight exposition. In the midst of a number of rather potent scenes, characters halt and explain their self-evident thought processes aloud. This unmerited emphasis on tedious clarification is only further compounded by an array of truly pitiable casting decisions.

Blomkamp tends not to shy away from stunt casting — before settling on Matt Damon, he approached Eminem to star in “Elysium” — and, in “Chappie,” Blomkamp makes the risky decision to fork over a significant amount of screen time to a cadre of non-professional actors. Vi$$er — a musician by trade — generally holds her own despite a few cringe-worthy exchanges in the film’s opening minutes. Ninja, on the other hand, positively flounders. Delivering each line as though reading a dictionary, Ninja’s words routinely register as forced. In turn, the rapper-turned-actor unwittingly draws an inordinate amount of attention to the stilted and explanatory nature of the film’s dialogue. Yet, although it’s easy to fault these performers for their lack of experience, even the film’s professional actors have difficulty adding any real depth to their delivery. Most egregiously, the usually capable Jackman is downright cartoonish as Deon’s arch-nemesis: Like a mullet-sporting Steve Irwin on Steroids, Jackman’s Vincent is so hopelessly ridiculous it’s hard to imagine him posing any substantial threat to Deon or to Chappie. With that being said, “Chappie” is not a film entirely devoid of quality.

As Chappie, Sharlto Copley is no less than revelatory. Performing with the aid of motion-capture technology, Copley’s rendering is one of immense physicality. Arms, legs, hands, torso: Copley employs the entirety of his body, bringing emotional range and complexity to the robotic Chappie. As an artificial construction, Chappie must learn like any other sentient being and thus, as Chappie, Copley faces the formidable challenge of enacting each segment of the human lifespan. Nevertheless Copley does so with stunning ease. Shifting easily between childlike innocence, teenage rebellion and the sobriety of adulthood, Copley compresses the intricacy of existence into the film’s succinct two-hour runtime.

Also worthy of commendation is the film’s exceptional finale. In the last 30 minutes of this otherwise disappointing venture, Blomkamp breaks from the film’s narrative constraints, in turn unleashing the pure anarchical sublime. Brilliantly staged slow motion, perfectly timed close-ups and unflinchingly bold musical accompaniment — hats off to composer Hans Zimmer, whose mastery of the electronic lends the film a physical, and vital, pulse: Blomkamp’s conclusion is an explosion of the spectacular.

More importantly, though frenetically paced, the final moments of “Chappie” refuse to sideline emotional catharsis and character maturation for the sake of superficial progress. Here, Blomkamp takes a breath, slows things down — where necessary — and delivers a string of poignant payoffs that will, if you have even the slightest shred of a functioning heart, leave you with a rather sizeable lump in your throat or, quite possibly, a splash of tears in your eyes.

If only the rest of “Chappie” had actually earned such an affecting denouement.

Contact Will Ferrer at wferrer ‘at’ stanford.edu.