Students for a Sustainable Stanford (SSS) and the Sexual Health Peer Resource Center (SHPRC) have collaborated to bring the first subsidized menstrual cup option to Stanford.

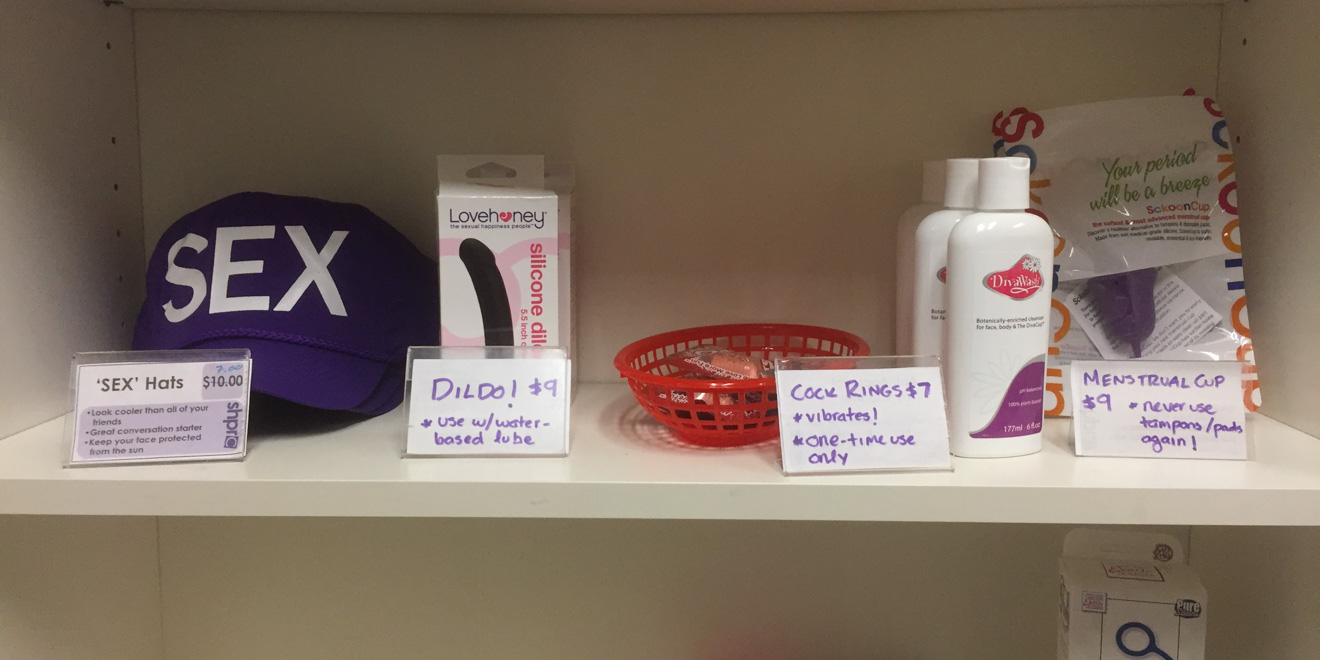

Menstrual cups, which can be worn for up to 12 hours, are a safer, more environmentally sustainable alternative to tampons and pads. Made of flexible medical-grade silicone, the reusable, bell-shaped cups are inserted similarly to a tampon and collect blood rather than absorb it. The cups are now available at SHPRC for $9, down from the market price of $39.

Andrea Contreras ’19 and Daily staffer Sierra Garcia ’18 of SSS spearheaded the initiative after hosting a “Sustainable Menstruation” conversation during winter quarter’s Waste Week, where students discussed different menstrual options and the barriers to trying them.

“I walked away from that [event] so inspired,” Garcia said. “I realized that we all had this shared experience of having been thrown a tampon when we were 13 and had to go to a pool party or whatever, and not really ever being able to talk about our periods very openly. It was really amazing to have an open conversation for the first time with other people.”

During the conversation, students discussed different menstrual options with little to no landfill waste, such as period underwear, reusable pads and menstrual cups. According to Garcia, many students mentioned that they would love to try out menstrual cups, but with prices at around $39, they just weren’t very accessible.

Normal inaccessibility was just one reason that Garcia and Contreras chose menstrual cups as their pilot product. Menstrual cups can be left in for half a day with virtually no risk of toxic shock syndrome — only one case of toxic shock syndrome related to the cups has been documented — making the product a more convenient and safer option than tampons. In fact, Garcia mentioned that Contreras began using hers for scuba diving, spending long days on the dive boat.

In addition, menstrual cups last two to five years, minimizing landfill waste and decreasing long-term costs, according to makers of the product.

“We thought it could be a really powerful tool for low-income students because about half of the people on this campus have no choice but to spend hundreds of dollars while they’re here at Stanford on menstruating,” Garcia said.

Garcia and Contreras initially faced some pushback from SHPRC when they pitched their menstrual cup collaboration idea last quarter: At $39 each, the cups would be out of SHPRC’s price range.

In response, Garcia and Contreras cold-called menstrual cup companies until one, Sckoon, offered them a slightly off-colored batch of 150 for $12 each. SHPRC agreed to subsidize them $3 further, and with the $3 SHPRC credit Stanford students receive every quarter, menstrual cups can cost as little as $6 for students.

SHPRC counselor Alyssa Liew ’18 was thrilled to see menstrual cups hit the shelves.

“Every body is so different, so you really need to feel out what is good for you, and I think that’s what’s cool about the SHPRC [cup],” Liew said. “It’s [a] very low investment and something that could potentially save you a ton of money over the next few years, or it’s just something like, ‘Oh, I tried it and it’s really not for me.’”

“But seriously, highly recommend,” she added.

Garcia echoed that the overall goal of bringing menstrual cups to Stanford was simply to make different options more accessible. Having more options, she said, is “really important for empowerment.”

After cost, Garcia explained, students’ biggest hesitation about using menstrual cups was rinsing them out in a public sink, as the cups must be washed before reinsertion.

“It’s a very valid concern, because it’s not very socially acceptable,” Garcia said. “For one thing, people don’t even know what menstrual cups are.”

But for Garcia, the benefits outweigh the potential discomfort.

After purchasing her menstrual cup, Liew went online for tips about cleaning it in a public restroom. Suggestions included bringing a water bottle into the stall to wash it there, cleaning it in the shower or using baby wipes in the stall. In addition, many dorms on Stanford’s campus include at least one single-stall, gender-neutral bathroom.

“For me, especially if it’s not in a crowded restroom, I don’t really mind cleaning it in the sink because it’s a natural process and I’m doing it for hygiene,” Liew said. “This is something I hope more people can become comfortable with.”

Currently, the menstrual cup initiative is a pilot program, but if there proves to be demand for them on campus, SSS hopes to make the cups a permanent product at SHPRC.

“If this is the one thing that I leave behind me at Stanford, that would be so fulfilling,” Garcia said.

Contact Tia Schwab at kbschwab ‘at’ stanford.edu.