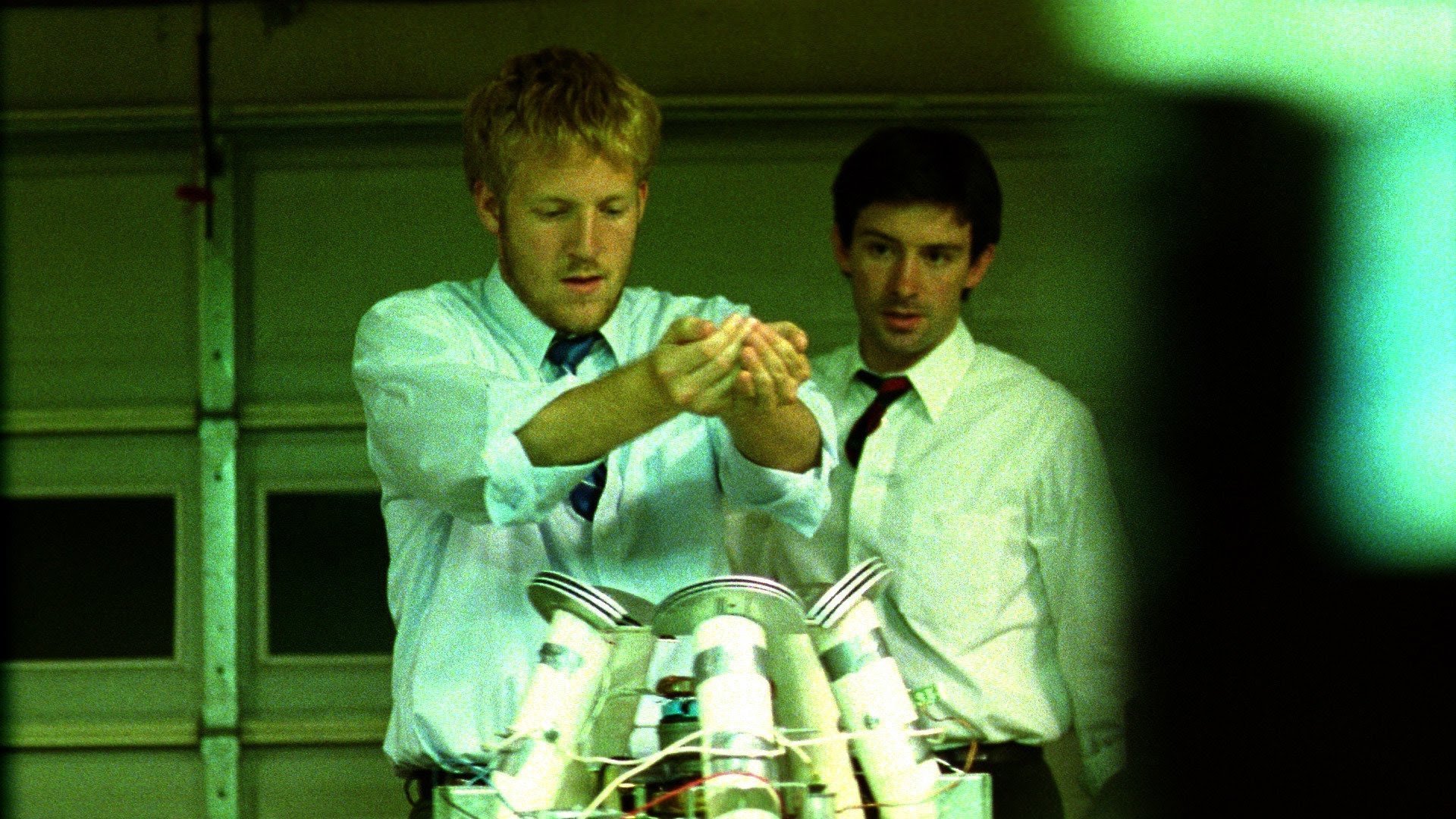

The 2004 film “Primer” is, in a sense, both mind-bogglingly entertaining and elitist. It stars Shane Carruth — who, not coincidentally, also wrote, directed, produced, edited and performed every other behind-the-scenes role — as a Silicon Valley-esque engineer who along with another engineer accidentally invents a time machine. The film is filled with technical jargon and dialogue that serves little to no plot significance but which is supposed to add to the believability of the film. The time machine, too, functions in an extremely roundabout way that, on one hand, solves many of the “grandfather paradox” time traveling issues that many movies face, but also alienates the audience if they really don’t understand what is going on — which was me for quite a while.

While taking a class on science fiction films, I’ve learned about the generally accepted academic definition of science fiction as “cognitive estrangement.” In that way, science fiction takes a wildly new concept (the “estranging” part) and breaks it down to a logical essence (the “cognitive” part). What makes “Primer” so compelling is how well the film fulfills this definition — not just for the sake of doing, but because how it “cognitively estranges” the audience is such an epitome of the beauty of science fiction.

With the time travel aspect of the film being so convoluted, I had to take a step back and really think about it. The science behind the engineers’ time machines is hard-hitting, and with the immense logic and technical aspects behind it, the time machine is rendered highly believable. At the same time, because it is so hard to understand on a first viewing of the film, to a certain point I really just wanted to shut the film off because I was incredibly frustrated. Even if I’ve learned that art is not always “made” for an audience, I feel that in a general sense, films are made for audience, if not public, consumption. Having a film so terribly complex and involves such intense scientific aspects that absolutely nobody can understand, let alone follow, can detract from a film.

I would recommend watching the film and looking it up if you’re intrigued. All things considered, it did win the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 2004. I’ll have to give it to “Primer” — after I went back, rewatched a few bits and did a bit of independent Googling in order to figure out how the time travel worked, I was stunned by how well the film fit together. The estranging aspect of the film, the time machine, is not really a new concept in science fiction, let alone film. Making the science behind the time machine so logically sound, at least from a viewers’ perspective, was very refreshing. In only 77 minutes, “Primer” achieves something that many films can’t: a fresh, intellectual look on a popular, often overdone genre — and on a small budget of $7,000, too.

Contact Olivia Popp at opopp ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that the budget of “Primer” was $77,000. The actual budget was $7,000.