“Sometimes scraps of memory like that can be the trigger that brings a story into being.”

In an interview with The New Yorker, Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami described how his latest short story “With the Beatles” was generated from his own memory. Murakami’s memory, the image of a girl clenching the 1963 LP “With the Beatles” to her chest — “A dimly lit hallway in a high school, a beautiful girl, the hem of her skirt swirling, ‘With the Beatles’” — yields a story that stirringly explores the vitality of youth and mourns the experience of aging.

The unnamed narrator in “With the Beatles,” a man far past adolescence, movingly explores the expendability of life in the retrospective voice. As in most of Murakami’s works, some of the short story’s most emotional moments include allusions to pop culture, music, history and literature.

“With the Beatles” follows the narrator’s reflection on his relationships with two girls — one, a girl glimpsed in a hallway, and the other, his first serious girlfriend. His girlfriend, Sayoko, he describes as having a “small voice,” “petite and charming,” “neat and clean and well groomed.” The narrator depicts Sayoko as a teenage girl — typified, and one-dimensional. The first girl, however, figures as something more for the narrator. He constantly revisits the memory of her, clutching onto The Beatles LP desperately; “What pulled me in was the vision of that girl clutching the album as if it were something priceless … There was the music, for sure. But there was something else, something far bigger. And, in an instant, that tableau was etched in my heart—a kind of spiritual landscape that could be found only there, at a set age, in a set place and at a set moment in time.” She is youth, a sensation Murakami’s narrator “unconsciously [longed] to relive.”

The unnamed girl and Sayoko act as foils to each other: One embodies youth and the other humanity, inevitably aging. It is in the narrator’s preference to the former (evident in his dedication to describing her abstractly, as a feeling he longs to recreate) that Murakami reveals the human tendency to idealize youth.

The narration opens with a reflection on old age. The narrator does not mourn his own maturity. He mourns the maturity of the “pretty, vivacious girls I used to know … now old enough to have a couple of grandkids.” Above all, he mourns the maturity of his dreams: “The death of a dream can be, in a way, sadder than that of a living being.”

Chronologically, the narrator follows his first serious relationship. The music that plays as he and Sayoko make out, “Theme from ‘A Summer Place,’” haunts his reminiscence; his homeroom teacher hung himself that same afternoon while he and his girlfriend made out.

Masterfully, Murakami shocks the narrative with a harrowing image — two teenagers in the midst of youth paralleled by suicide — and mirrors the emotional shock that follows a human taking their own life. He introduces his subject matter in a single, short and dramatic paragraph before moving on to delve into the narrator’s recollection, as if it is simply a passing thought, not dwelt on. Moving on so quickly from this paragraph, Murakami leaves an echo in the piece, an emotional jolt to remain with the readers. Murakami sets an emotional backdrop for the short story: A man reflects on the passing of life while death by suicide lingers in the background.

This scene, two adolescents embracing while a suicide takes place, represents Murakami’s larger theme: how life proceeds as death takes place, how the idealization of youth remains in memory while age progresses and how the memory of a relationship remains in place long after its end.

Throughout “With the Beatles,” Murakami explores the expendability of life, especially with regard to suicide. The narrator reflects on the unnamed girl, wondering if the LP she held, as if priceless, held any value at all. He wonders if the memory meant anything at all. He wonders if their lives mean anything at all, or if they are simply fleeting.

“I’ve heard it said that the happiest time in our lives is the period when pop songs really mean something to us, really get to us,” he thinks. “It may be true. Or maybe not. Pop songs may, after all, be nothing but pop songs. And perhaps our lives are merely decorative, expendable items, a burst of fleeting color and nothing more.”

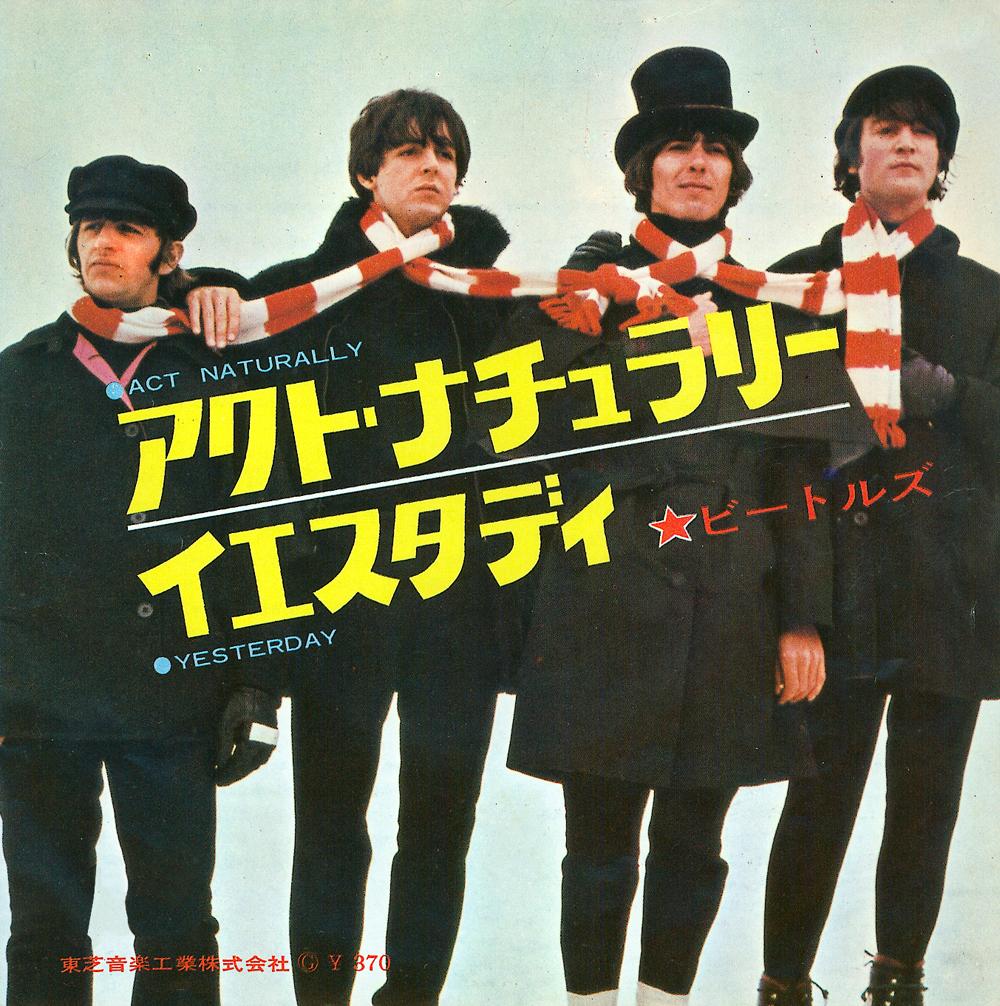

Music flares throughout the piece. Murakami’s affection for The Beatles seeps through his work—a reference to their album Rubber Soul in his 1979 novel, Norwegian Wood, and the 2014 short story “Yesterday” was titled after The Beatles’ hit—and weaves itself throughout “With the Beatles.” Music—a Mozart symphony, Sound of Music’s “Edelweiss,” Percy Faith, “Theme from ‘A Summer Place’ and The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beatles—saturate each scene. “Hello, Goodbye,” the narrator recalls, plays when he breaks up with Sayoko, his first serious relationship.

Murakami’s most masterful allusion frames his most dramatic scene — the narrator arrives at his girlfriend’s house to pick up her only to find her missing and instead finds company in her older brother, whom she was shy to introduce. To the narrator, Sayoko’s older brother is, in a word, disheveled.

Together, they sit at first in silence until Sayoko’s brother asks her boyfriend to narrate from his textbook. He reads the two final sections of Akutagawa’s “Spinning Gears”: “Red Lights” and “Airplane.”

“It was about eight pages long, and it ended with the line ‘Won’t someone be good enough to strangle me as I sleep?’” he recalls. “Akutagawa killed himself right after writing this line.”

Then, Sayoko’s brother abruptly confesses that he is plagued by a disease of memory gaps at length, gaps in which he fears to lose himself, gaps in which he fears to unleash violence. He likens these breaks of memories to breaks in music recordings.

The reader inevitably fears violence from Sayoko’s brother. The abruptness in Murakami’s prose, in explicating a teacher’s violent suicide and a girlfriend’s brother’s violent disease, grips the reader tightly. It raises the stakes in events past, it shakes the reader into an attentive awareness and beautifully invests emotions into “With the Beatles” characters.

Murakami’s short story ends with the revelation of a final suicide. The three of these suicides — his homeroom teacher’s, Akutagawa’s and the final one — trace the outline of “With the Beatles.” The motifs of memory gaps, suicide and The Beatles’ music silhouette a stirring narrative of a man’s reflection of past things.

The voice Murakami adopts in handling such heavy subject matter—objective, sparse—lends itself to deliver an incredibly emotional piece. His writing uses understatement to get at important truths. It’s in the piece’s impersonal voice that Murakami best delivers his sentiments.

Murakami’s newest piece delivers a poignant narrative mourning youth, the fragility of life and the experience of aging.

Contact Roberta Gonzalez-Marquez at robygzz ‘at’ stanford.edu.