Intro: Hi! We’re Mark and Nitish, and we (like most of you we hope) are practicing social distancing to help prevent the spread of coronavirus. We recognize that this is a super stressful time for a lot of people, and that many of you are being impacted by the virus in one way or another. So, we thought we’d do something that would hopefully lighten the mood. We are going to be watching and reviewing movies available on streaming platforms. Our column will be published (roughly) every week on Wednesday. We hope that you can watch along, send us your thoughts and recommend movies that you like or want us to watch. Best of luck to all of you in these trying times!

“I Lost My Body” (Released in 2019; watched by us on March 20, 2020)

A 2019 French animated film by Jeremy Clapin. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

Dear reader, I thought I was in my element.

Animation is my thing, my niche — at least I thought so. I eat, breathe and bleed these numerous drawings, and there is no other medium that can so effectively transport me to different realms. Whenever I read a book, I always imagine it animated in some way, shape, or form … it is how my brain operates.

But “I Lost My Body” is not the kind of animation that I am used to, and I spent quite a bit of time wondering what exactly made it so different. I, among others, am a child of Pixar, and having grown up in a world ruled by a gracious lamp overlord, this has largely shaped how we tend to see animation.

First, we often consider it kid’s stuff — a dismissive prospect that, in my opinion, only serves to limit a medium capable of infinite possibilities. Second, we generally see animation as a means of telling stories that could not so easily be told in live action. Imagine sentient toys, monsters running factories or a boy exploring the land of the dead — these are purely fantastical concepts explored to the fullest. I believe the medium has been used beautifully thus far — the lamp alone has created several of my all-time favorite movies — but “I Lost My Body” bucks these trends and throws me off my rhythm.

This movie follows the perspective of a severed hand making its way throughout Paris in order to reunite with the rest of its body. It previously belonged to a young man named Naoufel — he is orphaned, soft-spoken and relatively unaccomplished. As the hand makes its journey we see glimpses of Naoufel’s life and the events that led to him losing his hand. This movie becomes a ticking clock counting down to such a gruesome inevitability, which the filmmakers clearly love to tease, taunting the audience with several shots of the hand operating dangerous equipment. Jerks.

For starters, “I Lost My Body” is not kid’s stuff. The initial concept of a hand being severed from its body is macabre enough, but we also cover deeper themes and complex emotions that, with few exceptions, are often kept as subtext in other animated films. It is an exploration of a young man’s life and it does not shy away from its emptiness, nor does it guarantee any resolution. By the film’s end, there is no neat little bow to tie the experience together. “I Lost My Body” remains honest about life and what it means to live it. What’s lost is lost; what’s gained is precious. This frankness was initially quite off-putting to me.

But, this movie also stands out to me on a structural level. “I Lost My Body” uses the medium of animation to tell a mundane story through unconventional means, splashing a new coat of paint on top of more realistic and familiar struggles. The resulting product is a fresh new perspective to a tale we have likely seen before. There have been plenty of love stories, and many hit very similar beats — however, none of us have seen such a love story told through the memories of a severed hand as it crawls through pipes and takes out pigeons and rats (this hand has zero chill). The filmmakers, here, dare to use the medium in different ways.

These changes have caught me off guard — it is near akin to me seeing an oven used as a bookcase, or a washing machine used as a back massager. But, through these differences, “I Lost My Body” is truly allowed to stand out. If you are wanting to see animation used to tell different kinds of stories, and pushed to new heights, then this film is worth a watch. It’s runtime is short, but I must warn you, it will linger.

Nitish:

I’m still processing this movie, so I’ll start off with the easy parts: This movie is a masterpiece. It is utterly captivating and deeply profound, and there are many stunningly drawn frames that are going to be seared into my memory for quite some time. “I Lost My Body” is most simply a tale about a severed hand finding its way back to its body. But it is also an emotionally complex narrative about a young immigrant in France, dealing with the gap between his dreary life as a perpetually tardy pizza delivery person and the dreams from his childhood. It is also a lamentation on the cruelty of fate. It is also an incredibly visually arresting work of art. If it’s not obvious, I really like this movie (shoutout to Mark for recommending it).

The foundation of this movie is the touching narrative it crafts with Naoufel. The beautiful art adds soul to shots in a way that I don’t think any other medium could. We don’t so much see as we do experience the childlike wanderlust as he plays with a globe in Morocco, the reverence he has for his mother’s piano playing. The slump in his shoulders when he was upholstered by his boss at the pizza shop for being late (again) felt achingly familiar. We are captivated with his love for the voice from the intercom, with his optimism from an apprenticeship in a carpenter’s office, with his pain when he loses his hand, with his sorrow when he loses things more precious. We love with Naoufel, we grieve with Naoufel. The currency of art is the emotional connection it can form with its consumer, and it’s been a while since a movie has been able to move me so effortlessly. Naoufel’s story alone would be reason for anyone to watch this film.

But the beating heart of this film is the surreal tale of Naoufel’s hand finding its way back to him. In the past year I have started learning how to draw, and hands have easily been the hardest subject I have tried to render. They have also been the most rewarding, as when you correctly draw a hand, it feels like an entire soul rests inside it. This movie, in an impressive flex on struggling artists everywhere, draws the hand perfectly every frame it’s on screen. I’ve rarely been more engaged with a film as when I saw the hand fight off a few subway rats, tuck a baby into bed, watch a piano player, or grasp an umbrella in a courageous attempt to fly across Paris. The hand seems to embody the noble, free and indomitable love of life that is most often found in children. In watching the hand return to Naoufel I felt that love return to me.

The ending ties the different thematic pieces about fate and choice in a profound but ambiguous way. I’m doing my best to leave it vague, but it feels bracingly honest and hopeful at the same time. The ending is also breathtakingly beautiful: The way that starlight played with falling snow on an abandoned rooftop will stick in my head for a long time.

In sum, this is one of the most extraordinary movies that I’ve watched in a long time. I seriously cannot praise it enough. It is both emotionally grounded and fantastical. This is easily my new favorite animated film, and has leapfrogged its way into my all-time favorite movie list. All this being said, the best reason to watch it is because it’s the type of film you can watch in order to flex on your less cultured friends: “My favorite movie from last year was a French animated film about a severed hand trying to reunite with its owner and how that relates to the failure of humanity to grapple with a deterministic world. Oh you liked ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’? That’s good too I guess.” So while it’s an incredible movie that everyone would be served by watching, you should all watch it because it will allow you to ascend to the highest tier of pretentious Stanford students: the one who appreciates foreign film.

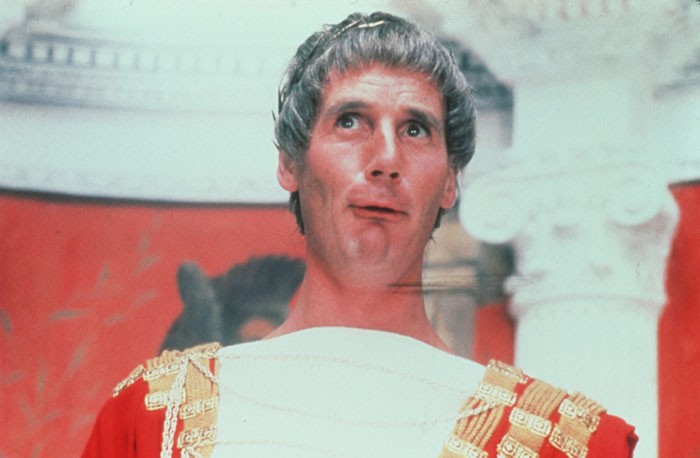

“Monty Python’s Life of Brian” (Released in 1979; watched by us on March 21, 2020)

A 1979 comedy by the group, Monty Python. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

I admit, dear reader, that in these dark times I needed a reminder to always look at the bright side of life. Granted, I did not expect to get such advice from a row of crucified Brits, but I suppose it’s all about perspective. I should have expected nothing less from my first foray with Monty Python.

As a humongous fan of Douglas Adams’s “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” I was pleasantly surprised to find the same sort of irreverent — and delightfully stupid — sense of humor here. Truly, this is the closest thing to a “Hitchhiker” film adaption I had ever seen … and that includes the numerous actual “Hitchhiker” films that have since been produced. And I believe my reasons for liking “Life of Brian” — as moronic and chaotic as it might be — are very similar.

“Life of Brian” follows the life of Brian (duh) Cohen, born in the stable next door to Jesus Christ. In adulthood he joins one independent group (among many) dedicated to (sort of) fighting against Roman tyranny, but after a series of incidents, he is mistaken as the true messiah. What follows is a nonsensical religious satire — and by nonsensical, I mean aliens get involved somewhere in the second act. And everybody just sort of accepts that.

I should be clear — “Life of Brian” does not need to make sense. In fact, it would arguably defeat the purpose. Monty Python aims to do one thing, and it is to make people laugh as hard, and as often, as possible. Instead of wasting time attempting to tell a fully realized, smooth or coherent narrative, this film is instead structured more as a series of sketches leading roughly into the next. This allows our favorite comedy troop to create odd, absurd scenarios, like merchants who force their patrons into haggling, or roman soldiers who end up resembling more latin teachers — all while hardly even glancing at the bigger picture. In fact, the first half of the movie is hardly even plot relevant — but it doesn’t need to be. These tangents are funny. Without them, “Life of Brian” might arguably be a better story, but it would be a less funny comedy, and this film aspires to do the latter.

In an earlier article of mine, I made similar observations with “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” and I am thrilled to find that this odd sort of storytelling — this unapologetic narrative rule breaking — is not exclusive to Douglas Adams. This style of comedy appears to be a staple of a time and place (both “Hitchhikers” and “Life of Brian” were released in the late 1970s) and I am excited to learn more. I want to see what other types of nonsense these madlads are capable of.

Nitish:

“Life of Brian” is a satire following a man named Brian born in the stable right next to Jesus. At the time of its release, it was highly controversial, and it was protested quite a bit in the U.S. by religious groups. It is also regarded as a comedy classic. So, is the fuss deserved?

I have to admit, a bit shamefully, that I think this movie is overrated. There are absolutely hilarious moments: the beginning where the three wise men see Mary and Joseph with halos around themselves after trying to give myrrh to the wrong baby was hysterical. The closing shot of everyone singing while they’re being crucified is a wonderful bit of absurdist humor. But as a whole? The movie didn’t really work for me despite a few stand-out moments.

Some of this comes from timing. I frequently felt that jokes overstayed their welcome. For example, a character from Rome’s name is ‘Biggus Dickus’ — ok, I laughed. But this one (fairly stupid) pun was the basis of a five-minute scene. Another frequent gag revolves around a few characters’ speech impediments. Personally, I didn’t find this funny to start off with, but even if you did I can’t imagine that you still found it funny after they used the same joke for another five minutes. There’s a great shot of Brian opening his windows to see a gathered crowd of devotees, but I thought that was overused too.

Probably a more serious issue is that I often felt the jokes weren’t that sharply written. Blasphemy, I know. Some jokes were exceptional, but at other times, I just wasn’t that amused. It also wasn’t as incisive as I thought it would be. Comedy doesn’t need to be a philosophical argument in disguise, but it felt like the “Life of Brian” was setting itself up to do this and didn’t deliver.

This opinion might be as heretical to comedy fans as “Life of Brian” was to Jesus fans (sorry, I wanted sentence parallelism). But I think my best metric for a comedy movie is how often I laughed, and I didn’t laugh a whole lot.

So yeah. I hope that you had a different experience than I did, and laughed a lot more. In any case, I’ll catch you soon.

“Goodfellas” (Released in 1990, watched by us on March 22, 2020)

A 1990 crime film directed by Martin Scorsese. We watched it on Netflix!

Mark:

I had a personal stake in watching “Goodfellas” — I suppose I considered it research.

Hm … hold on a moment.

I am NOT planning on joining the Mafia. Yes, copper, please take me off your watchlist. I am currently dabbling with creating my own mobster story for a “Dungeons and Dragons” campaign (I’m sure, in the span of two sentences, my street cred has sunk like a stone). There is something irresistibly glamorous, appealing, pitiful and even envy-inducing about the movie gangster, and this is a luster I would like to replicate in my own works. For this reason, I am diving headfirst into the classics! Indulge me, dear reader, as I attempt to discern not only what makes “Goodfellas” work so well, but what traits make the gangster genre so unique.

Based on a true story (a fact I had just found out, by the way) “Goodfellas” follows Henry Hill, from his beginnings as a child enamored by the local mob, his peak as a fearsome mob associate, to his catastrophic — though rather inevitable — downfall. Those who have seen 2019’s “The Irishman” (also directed by Scorsese) might notice very similar beats … in fact, one movie greatly echos the other. Yet, I found myself enjoying “Goodfellas” more.

It might help me that this movie is a whole hour shorter … in fact, that probably is the reason. But I also feel that Henry Hill in “Goodfellas” makes a more engaging lead. By starting Henry’s arc as a teen, the film gets to gradually ramp up the protagonist’s crimes, slowly replacing a child’s idealistic view of the mob with its genuine horrors, and once we’ve reached the peak, we get to see the organization fall apart. This ebb and flow is, for whatever reason, not as noticeable in Scorsese’s latest work. And the comparative boredom Henry feels living a normal life is much more succinct — and just as impactful — as the last 40 minutes of “The Irishman.”

But as for “Goodfellas” itself, I was especially struck by the violence. Scorsese’s gruesome kills and bloody murders are simply a part of the environment — the most horrible of crimes are dished out with a surprising casualness. This is exemplified by one scene in particular, as one established character is murdered to avenge a past and forgotten-about transgression. In one moment, the victim is laughing along with his killers, looking forward to getting honored; then in the blink of an eye, he is shot without an ounce of feeling. The film itself doesn’t dwell on it — the act itself takes three seconds. The spite behind the killing, too, is conveyed simply through Henry Hill’s casual narration: “They even shot Tommy in the face, so his mother couldn’t give him an open coffin at the funeral.” In any other movie, this scene would be accompanied by blaring instrumentation (or, if this was a Tarantino picture, maybe an explosion or two) — in “Goodfellas,” it feels unsettlingly natural. Because that is what the mobster life is like.

I believe what makes “Goodfellas” (and perhaps, the rest of the gangster genre, should I have the chance to experience it) so poignant is how everything just sort of happens. Like its characters, the film moves along with an ease that quite frankly speaks for itself — and its brilliant filmmaking, as opposed to taking the limelight, plays a subtler (but crucial) role in portraying this gangster lifestyle. Though I’ve spent most of my word space talking about what this gangster lifestyle is, I would like to at least mention the mind-melting cinematography, the surgical editing, the brilliant song choice, some of the snappiest and most memorable dialogue I had ever heard, and these great performances. Joe Pesci as Tommy especially stands out to me as one of cinema’s greatest characters, and he will inevitably get a separate article gushing about — oops, I meant “analyzing” — him.

I could not stop thinking about “Goodfellas” — even now, I am itching to rewatch it. The gangster life is appropriately horrifying but undeniably addictive, and perhaps that should frighten me more than it is right now.

Nitish:

“Goodfellas” is a crucial film in the American cinematic canon, and for good reason. It has sharp dialogue, well-constructed characters, an excellent score and phenomenal direction. But its best quality is the fact that it is the quintessential American tragedy. American culture has long had a fascination with outlaws. Here, Scorsese picks the fantasy apart, laying bare the greed and venality at play. Like he does in “The Wolf of Wall Street” and “The Irishman,” Scorsese aims to show that these violent delights truly do have violent ends.

The lens that Scorsese uses to deconstruct the mafia is the character of Henry Hill. He starts off young, and we can see the allure that the mob has, the sense of community it provides. When Henry gets “pinched” for selling cigarettes, the mob is waiting outside the courtroom, congratulating him for “popping his cherry” and not giving anyone up. In one scene, gangsters threaten a mailman in order to prevent him from bringing Henry’s parents the truancy letters that he is stacking up. As Henry grows older, we can see the money that he lavishes on restaurants, the respect he gets from everyone. He films these parts breezily: I was reminded of the first time I went to a movie theater concession stand. Flashing lights, artful posters, and so much food. Like me, Henry tried to get everything, believing all of the ads and paying no attention to his emptying wallet.

But take a closer look, and the ice cream only fills half of the cup, the nachos are unhealthy and the prices are exorbitant. Henry though, suffered more than the stomachache that I was left with. After a string of affairs, his marriage and home life were wrecked. He laughed along with Tommy shouting at a waiter and then looked on in horror as Tommy shot him. His friends turn against him, and he ends up fleeing to witness protection in order to escape with his life. Scorsese, a Catholic, seems preoccupied with sin: While Henry’s choices may seem alluring, may provide short term pleasure, they cause deeper pains. Like any good tragedy, the horrors that arise later in the movie are a direct result of Henry’s choices. If not for his lust, his greed, he might have a marriage or friends or a life outside the confines of a DOJ safe-house.

There’s a lot more to praise in this movie. The acting is phenomenal, everywhere. The dialogue is sharp. The direction has Scorsese’s trademark style, and frames the thematic pieces of the movie well. As Mark notes, Scorsese handles violence with a matter-of-factness that gives it power. In lesser movies (I’m talking to you, Quentin Tarantino) violence is pulpy and we lose track of the fact that there are actual people who are dying. There’s a moment where Tommy and Jimmy laugh about the resemblance that a character in a painting has to a body in the trunk of Tommy’s car. It’s morbidly funny, and we can see the horror on Henry’s face just as Scorsese pans up to show that the man in the trunk still has a little life to him. Violence in “Goodfellas” is made banal, and it is all the more brutal and horrifying for it.

This is about as close to a perfect movie as you can find. That being said, Mark is dead wrong, and “The Irishman,” Scorsese’s more recent movie, is better in every way. Hopefully, more on that later!

Contact Mark York at mdyorkjr ‘at’ stanford.edu and Nitish Vaidyanathan at nitishv ‘at’ stanford.edu.