A day in the life of a Los Angeles film production assistant is a far cry from the glamor of the Dolby Theatre carpet. Shuffling through paperwork, running between scenes and carrying styrofoam coffee cups across scalding Hollywood lots are just some examples of the redundant ‘grunt work’ expected of the position — most wouldn’t expect a recent Stanford graduate who dreams of becoming a screenwriter to sink their teeth into such a lowly job. But this is where many great screenwriters begin their career in the movie industry. To most outsiders, Hollywood appears a place that generates numerous “overnight success” legends. Only those who are in the industry can tell you that the real magic is hard work.

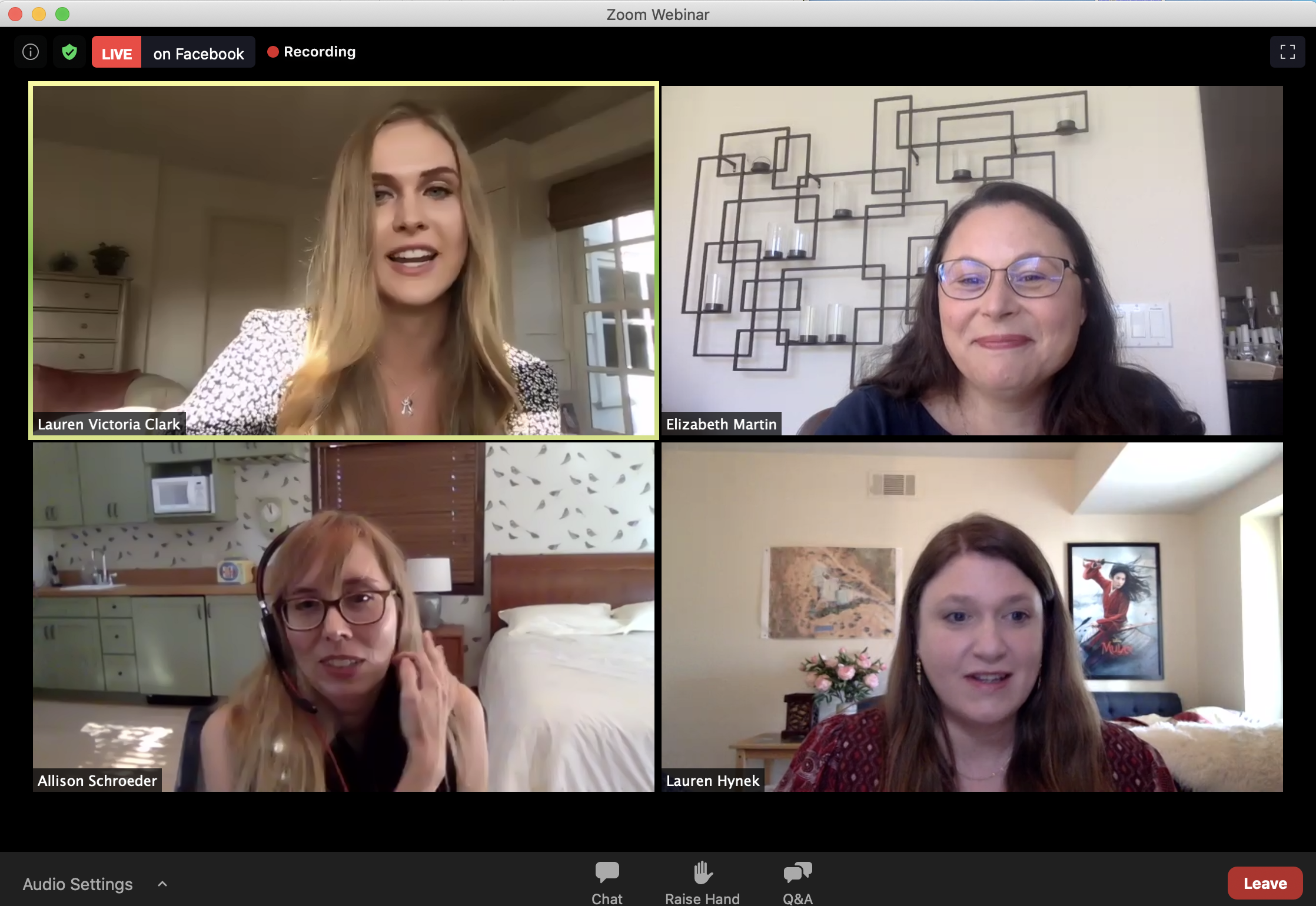

The Aug. 3 “Arts Alumni: Live from their Living Room” webinar presented by Stanford Arts and moderated by Lauren Clark ’20 showcased the honest –– and oftentimes downright hilarious –– voices of the female screenwriters behind “Hidden Figures” (2016) and the live-action “Mulan” (2020), Allison Schroeder ’01, Elizabeth Martin ’00 and Lauren Hynek. Musing about their paths to success, their undergraduate experiences and the newfound course their industry is taking, the friends’ chemistry exuded through the lively hour on Zoom.

The secret to survival in the film industry is surprisingly straightforward –– to dream big while tackling initial ‘grunt work’ with gusto. Longtime duo Martin and Hynek, Stanford and Brown University alumnae, respectively, had ostensibly bright futures in film ahead of them after graduation. The “Mulan” (2020) screenwriters had pursued drama and psychology majors in college, but despite their prestigious degrees, Los Angeles quickly humbled them. Taking a day job as a background actor to break into the industry, Martin recalled being treated “like cattle” at times on sets. The Stanford alumna went on to reflect on the invaluable lessons in moviemaking and the intricacies therein she gained from such modest circumstances.

“Sometimes, the directors would chat with us and tell us what they were doing and what was happening, and certainly the camera people and props people were happy to talk about what they were doing and why … It was really useful,” Martin said.

Schroeder, the quick-witted mind behind “Hidden Figures,” followed a more unconventional route to screenwriting after studying economics and a self-designed film individual narrative major at Stanford. Finding herself lost after 9/11 and amidst a transforming economy, Schroeder “got the guts” to quit her job as a financial analyst and pursue her passion as a screenwriter. After finishing her graduate degree at the University of Southern California Film School, she spent six months attempting to secure a production assistant job for “Pineapple Express” (2008), or what she lightheartedly dubbed “[that] stoner movie.”

When she caught a break with “Hidden Figures,” her mathematical side wasn’t the only advantage she bore. “I [already] had a certain amount of knowledge from working at NASA — my grandmother and grandfather had been engineers [there] — so I’d grown up around it to a certain extent,” Schroeder said. This edge didn’t keep her from being starstruck, however. “It’s amazing when you go onto set, and you see Octavia Spencer and Taraji Henson and Janelle Monet, and then you ask for a photograph, and they’re like, ‘Yeah, of course — you’re the writer, you’re being silly,’ and you’re like ‘Okay!’”

Getting there took time, though, and Schroeder looked back to her 25 year-old self running in the heat to get coffee with pride. “You have to be willing to do the grunt work,” she said. “Going and getting people coffee, being an assistant, being around people and learning from people and being willing to sort of start at entry level … don’t be above that, because that’s part of [the process]. There’s no linear path [or] one way to do this … everyone’s story of how they ‘made it’ is so wacky and weird normally that you just have to go for it.”

“Overnight success is like, 10-15 years into the process,” Martin chimed in. A defining highlight amid this process for Martin and Hynek came when they heard veteran Hollywood composer Alan Menken would score their newest animated film,“Spellbound.” Chuckling, Martin reminisced about her reaction to the news: “I full-on wept into my computer when he played his medley of greatest hits the first time. You know, I’m 6 feet away, trying to hide my face [behind the screen].”

Climbing the ladder to these moments also heavily necessitates networking, she emphasized, and establishing long-term relationships is its keystone. As with most things in the industry, making connections is a lengthy process, but can reap worthy rewards: “You’ll sometimes think, ‘I’m treading water, and I’m not making a difference,’ but … like five years later, somehow that contact you made will materialize into a job,” Schroeder added.

This physical networking has come to a screeching halt due to COVID-19, but virtual platforms still hold value and have actually lightened the load for some. To Martin, who often found herself weaving through the labyrinth of LA traffic to meet contacts prior to the pandemic, being restricted to a computer screen has somewhat eased communication. Interrupted on-set experiences and collaboration are just one factor of the multifaceted change sweeping the industry, though.

As advocates for gender equality in Hollywood, the three screenwriters are witnessing an increasingly equitable wave hitting screenwriting and movie production, but it’s taken time to build momentum. In such a capital return-oriented industry, “the main driver [of change] is not the goodness of people’s hearts — it’s economics,” Martin said. “The money is not in the stories about straight, white, middle-aged men [right now]; it’s in diverse experiences.” As inclusive projects currently have better investment returns, Martin is optimistic about the industry’s trajectory. “It’s only going to continue, and that’s wonderful. People are using their wallets to say what they want to see in the world,” said Martin.

While it is vital to recognize the diversity of what is displayed on screen, it is crucial that those behind the scenes spring from manifold backgrounds as well. “It’s taking a little extra time — people are realizing more quickly that diversity on the screen gets them money, and they’re catching up to the fact that we need to be more inclusive in who is telling those stories as well,” Hynek revealed. “But I think there’s at least a willingness there — it is still slow to see it actually come to fruition, but there’s at least an awareness, which is the bare minimum.”

Although domestic filmmaking is turning a new page with increasingly diverse characters and contributors, overseas audiences are less willing to flip the script. “The one caveat to this [progress] is [that] almost all indie production is pre-financed by foreign pre-sales, and a lot of the world does not have as good an appreciation of inclusivity as the U.S.,” Martin said. Though financial incentives to cultivate inclusivity are almost commonplace among American studios now, such diverse films do not always fare well in international theaters. Jokingly interjecting, Hynek voiced that “even in the U.S., the bar’s not high, folks. [But] the bar’s a lot lower [in] other places.”

Regardless, “the stone is rolling,” Martin remarked.

Providing a lively lens into the woman’s experience behind the scenes, Schroeder, Martin and Hynek’s webinar thoughtfully moderated by Clark was a testament to the patience, perseverance and palpable ardor needed for the ever-evolving American movie industry.

Contact Annie Li at ALi21 ‘at’ thehill.org and Nicole Johnson at nicole.djohnson ‘at’ comcast.net.