Aug. 9 marked the 38th celebration of International Day of World’s Indigenous People (IDWIP). According to the United Nations, this international holiday “marks the date of the inaugural session of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations at the United Nations in 1982.”

This group was established “with the mandate to develop a set of minimum standards that would protect indigenous peoples.”

According to the World Bank, “Over the last 20 years, Indigenous Peoples’ rights have been increasingly recognized through the adoption of international instruments and mechanisms, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2016, 23 ratifications of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention from 1991,” and many more reparations.

Stanford’s Indigenous history

Stanford was built on land belonging to the Muwekma-Ohlone Tribe. Despite these roots, Native American organizations were introduced on campus nearly 90 years after the University’s establishment. The Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) first hosted a powwow in 1971, followed by the establishment of the Native American Cultural Center (NACC) in 1974. Later, Native American studies were also integrated into the curriculum offered at Stanford.

Currently, Native American students only make up about one percent of the undergraduate Stanford population, a demographic which includes American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. However, small numbers have not stopped Native American students from building a community at Stanford.

School-led organizations

The NACC is a university and student-led organization located in the Old Union Clubhouse. Here, Native American students join together in various activities and programs, all centered around forming relationships.

Every year, the NACC holds an orientation for incoming Native American and Indigenous freshmen and transfer students. For two days, the Stanford Native Immersion Program (SNIP) welcomes these students and helps them adjust to Stanford.

Additionally, the NACC hosts multiple events for Native American students throughout the year, such as alumni events, dinners, trips and other social opportunities for people to connect.

Moreover, Native Americans are included in Stanford’s group of ethnic-themed houses through Muwekma-Tah-Ruk. Students that live here “take a credit-bearing seminar class either fall or winter quarter to explore significant cultural identity, legal, language, and land issues through speakers, discussions, and events.”

SAIO and its subgroups

In addition to NACC, the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) also promotes unity for Indigenous peoples. SAIO was founded in 1970 after a larger number of Native American students enrolled at Stanford than ever before.

SAIO also organizes Stanford’s Native American Big and Little Siblings, which pairs incoming Native American students with upperclassmen.

“We organize a lot of events for our community to hang out together, to study together, to learn things, to bring Indigenous people on campus to talk about issues,” said Elsie DuBray ’22, who served as a Siblings coordinator her sophomore year.

One of the program’s events involves “going to Alcatraz to honor the occupation of Alcatraz during the American Indian Movement … There’s a sunrise ceremony and we get tickets … then we also have a candlelight vigil that day.”

These bonds are further established and strengthened through subgroups within SAIO, like the Stanford Powwow and Hui o Na Moku.

Every year, the Stanford Powwow Planning Committee prepares a powwow that occurs on Mother’s Day weekend. Jade Goodwill ’21 is the current Powwow co-chair and has been involved with this group since her freshman year at Stanford. Growing up, she and her family had a tradition of attending powwows.

“My family has always been involved in the powwow trail, so I knew coming into Stanford it was something that I wanted to do,” she said. “The powwows at Stanford are one of the only times where you can see that many Natives on campus and the Palo Alto area, so it’s very heartwarming.”

Powwows are a celebration of Native American and Indigenous culture and the values that have been upheld for generations. During a powwow, participants join together to sing, dance, raise flags or, at times, compete when dancing. Each year, various powwows are held throughout the United States, but there is only one at Stanford.

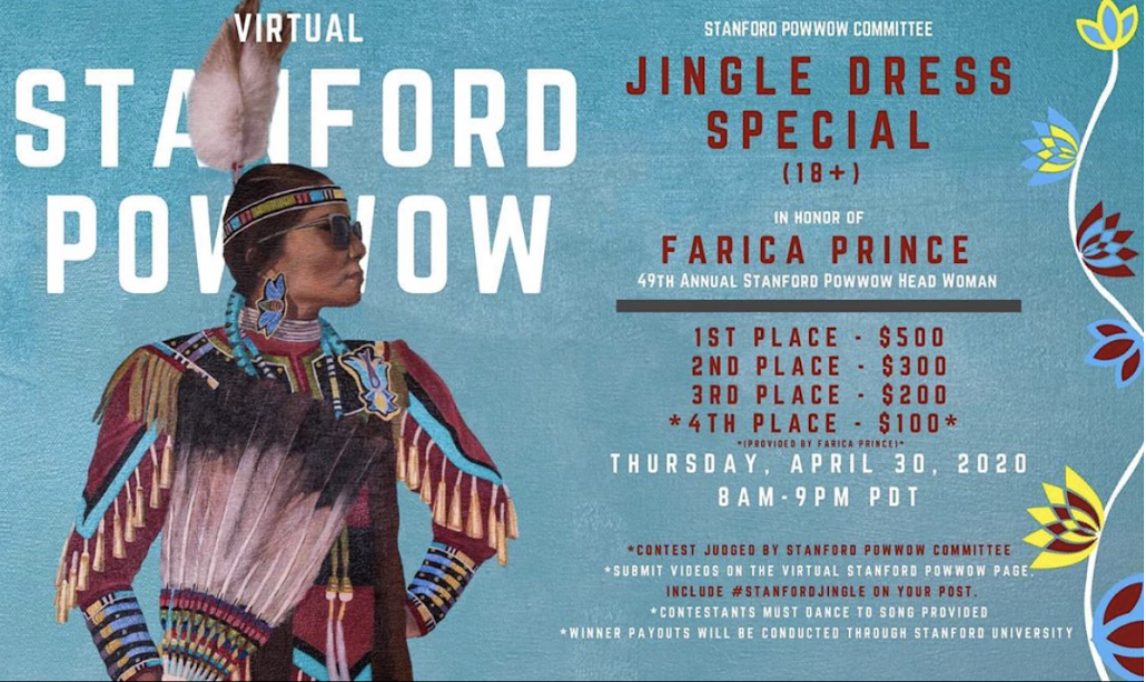

Because of the pandemic, Stanford Powwow had to cancel its in-person 49th annual powwow and subsequently chose to host a virtual one instead throughout May and June. According to Goodwill, people would record a video of themselves completing a part of a dance and send it to judges who would then rate the performance.

Outside of Native American organizations, there is also a group specifically for Hawaiian and Pacific Islander students, Hui o Na Moku, which was co-founded by Ma’ili Yee ’20 in 2018.

“There’s a need for a group centered on Pacific Islander culture and to address the appropriation that often happens in other groups and to provide support for Pacific Islander students,” said Yee.

Since Hui o Na Moku’s establishment, members have taught a University class on Hawaiian culture and planned to hold a conference, which was canceled due to the pandemic. Additionally, the club held a protest last October to rally against the construction of a 30-foot telescope that was set to be built on land that is sacred to Hawaiians.

This spring, three members of Hui o Na Moku, as well as professor of anthropology Michael Wilcox, taught the class NATIVEAM 126: Mo’olelo Aloha Aina: Hawaiian Perspectives on Storytelling, Land, and Sovereignty.

One of the first of its kind, this class focused on Hawaiian history, culture and activism.

The class “was primarily discussion-based with readings from various specific authors and video makers. We had a very mixed class of Native Hawaiian students, other Pacific Islanders, and all kinds of other students,” said Vance Farrant ’21, a co-founder of Hui o Na Moku who helped teach the class.

Keoni Rodriguez ’21 helped manage the social activism and educational component of the class.

“It was a really refreshing experience to be able to have that space, and it’s still a Stanford class … but it functioned in a very Hawaiian way … We established norms for behaviorism that reflected Hawaiian values that might not necessarily be the same for a Western-style classroom,” they said.

The future of Native American and Indigenous student groups at Stanford

Although there are many organizations and clubs that help preserve and influence communities at Stanford, it can be hard for smaller organizations to grow.

Farrant explained that although the University is helpful, guidelines for clubs are rigid.

“Stanford can only go so far to actually support … real, different ways of doing things as an organization,” he said. “That’s why some groups didn’t become a Stanford club, because it comes with certain restrictions and hierarchical leadership and oversight.”

“All of our work would improve in terms of benefiting the community if they developed different models of running our organizations and doing it in a more community horizontal leadership way rather than just hierarchy,” he added.

Similarly, Rodriguez noted the importance of representation at Stanford and the need for more Pacific Islander faculty.

“We would like to see more Native faculty,” Rodriguez said. “It can be a really frustrating and alienating experience when other communities have that opportunity and we don’t.”

“When it comes down to it, we just need Stanford to be responsive to issues that are important to the Native community and asked in ways that are actually substantial,” said Farrant. “And hopefully, not do this thing where they wait for years and people to graduate so that they never have to do anything.”

Contact Elizabeth Wilson at elwilson ‘at’ s.sfusd.edu.