After finishing up my senior year of high school virtually, checking off assignments, completing readings and writing essays, I did not expect to learn much more over the summer. For many seniors, and students of all ages really, distance learning had been exhausting. The end of the year was anticlimactic due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Motivation ceased, while doing assigned work required a new type of self-discipline. It was even isolating at times, as interactions with friends were done solely through a computer screen. This experience is the reason why I was intrigued by the Three Books program when it was announced to us, particularly when the topic of grit was brought up repeatedly.

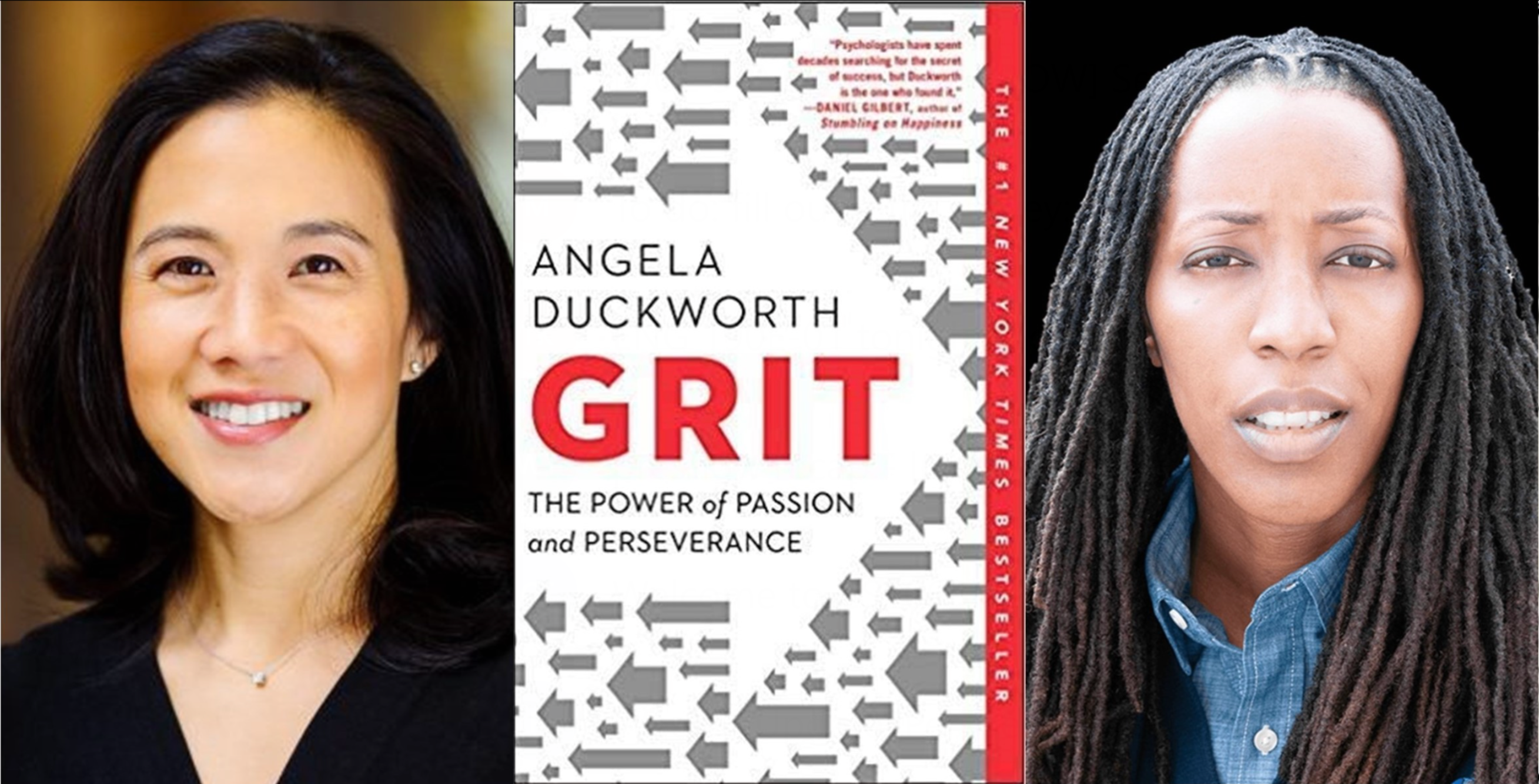

The Three Books program is a tradition designed to offer incoming students “common and shared intellectual experience” through a combination of readings with a broad theme. The 2020 theme was “Education and Character” and consisted of a line-up of books and articles chosen to enhance students’ knowledge and have them question their preconceived beliefs. The dictionary definition of grit is “firmness of mind or spirit” and “unyielding courage in the face of hardship or danger.” Two authors prominently featured in the collection, Angela Duckworth and Bettina Love, delved deeper into the concept and offered an important conversation through their work. The Class of 2024 and transfers had the opportunity to listen to both authors speak during New Student Orientation.

Angela Duckworth, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, is the author of “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance,” which was the first book on the reading list. As a psychologist, Duckworth takes a scientific approach to grit through her book, exploring the science of hard work. She defines grit on her website as “passion and perseverance for long-term goals” and uses a self-made test named the “Grit Scale” to quantify and measure the grittiness of an individual. “Grit,” divided into three parts (What Grit is and Why it Matters, Growing Grit from the Inside Out and Growing Grit from the Outside In), provides studies and anecdotes from Duckworth’s own life and “Grit Paragons” to explain her research on grit.

At NSO, Duckworth recalled growing up knowing that she wasn’t the “smartest” person. The combination of experiences of not being the “top-dog” made her question what more there was to success and begin researching the psychology of grit. At the opening of her book, she explains her experience studying cadets at West Point, which, in the past decade, has been collecting data on grit. From that data, Duckworth has come to believe that grit still remains a top “predictor for success.”

In the book’s third chapter, “Effort Counts Twice,” Duckworth explains how grit creates skill that leads to achievement. She discusses how when we see a “dazzling performance,” whether it be on a field, in a spelling bee or at a concert, people “default to labeling that person a ‘natural,’” or talented. According to her, labeling someone as talented distracts us from the hard work that produced the result. Despite talent playing a role in achievement, it is not the ultimate factor in determining success. Two equations from Duckworth show this: “talent x effort=skill” and “skill x effort=achievement.” In this case, talent is a boost to developing a skill, but effort is what takes skill to the next level.

Chapters later, Duckworth advises that grit, rising up to the challenge, requires an individual to immerse themselves in a “gritty culture.” This surrounding environment demands one to approach tough situations and offers camaraderie. With effort through practice, learning and support, the student can acquire skill and improve their grittiness. With continuous effort, they can achieve their goal.

Duckworth also explains that for the Grit Scale, people tend to score higher on perseverance than passion. Grit is about having a “life philosophy,” or “holding the same top-level goal for a very long time.” She writes that passion is not just doing what one loves, but “staying in love with it.” It’s all about “consistency” not “intensity.” Developing one’s passion, though, is not necessarily a bad thing. Passions take time to discover, and starting with extracurricular activities that feed your interests is crucial. In the chapter “The Playing Field of Grit,” Duckworth introduces the “Hard Thing Rule,” a four-part general idea of how one should approach an extracurricular activity. Part two states that you’re allowed to quit to move on to another “hard thing” that possibly interests you more, but not until you “finish whatever you began.” “You can’t quit on a bad day,” says Duckworth. Part three makes it clear that you “get to pick your hard thing” to cultivate your grit. You have the freedom to select from what interests and delights you to find your top-level goal.

Finally, in the second section, Growing Grit from the Inside Out, Professor Duckworth speaks on purpose and hope. Purpose is another source of passion — it is the “intention to contribute to the well-being of others.” This interest could start off as “self-oriented,” but eventually becomes something “other-centered.” Taking your passion to have an impact on others grows grit. Hope, as Duckworth describes it with the quote “Fall seven, rise eight,” is getting up again despite adversity. It is optimism and a growth mindset. The idea of yet, of potential, of still working out the problem and failing at some point to persevere and reach the achievement.

While the previous points derive from psychology, Bettina Love offers a more intersectional, historical and educational approach to grit. Love is the award-winning author of the book “We Want to Do More than Survive,” and the Athletic Association Endowed Professor at the University of Georgia. In 2020, she co-founded the Abolitionist Teaching Network, which aims to “develop and support teachers and parents to fight injustice within their schools and communities.” She is also a public speaker that discusses a diverse range of topics, including abolitionist teaching, anti-racism and inclusion. For the Three Books project, students read an article by Love called “’Grit Is in Our DNA’: Why Teaching Grit Is Inherently Anti-Black” and watched Love’s TED Talk “Hip Hop Grit and Academic Success.”

The TED Talk begins with Love’s experience as an elementary school teacher, teaching at an “under-performing school” with a majority Black student population. She described how she connected with her students through the “culture of hip-hop.” She saw students bring this culture into the classroom through what she called “organized noise,” or rhythmic collaboration. Furthermore, Dr. Love expressed that those who “breathed” hip-hop had “hip-hop sensibilities,” or character strengths, that included social and emotional intelligence, improvisation, curiosity, optimism and grit. These strengths aren’t something new. In fact, they’re a remnant of a history of oppression and unthinkable discrimination.

She recalled the trip she took to Ghana, describing the history “of terror, trauma, labor, [and] grit” of enslaved Africans and the revelations she had regarding Africa. She visited several sites that were reminiscent of inhumane terror. This includes a river named “Dunko Nsuo,” the name translates to “slave river,” where those captured were bathed, fed and branded by hot iron. She visited the Cape Coast Dungeon, where, after trekking hundreds of miles from Dunko Nsuo, men and women were imprisoned with poor ventilation and barely enough food to survive. After weeks in the dungeon, those still alive were loaded onto a ship and shackled to prevent rebellions. The ones who arrived in the Americas were, according to Love, “superhuman.” “They fought… survived diseases, starvation, beatings,” Love writes, “and the human loss of never returning home again.”

The way that American educators omit the history of endurance of Black people in teaching grit to students is a major problem for Bettina Love. She agrees to an extent that children need grit to be successful in life, but measuring “African-American students’ grit while removing no institutional barriers” is deeply harmful. Stories that “remove [the history from] both sides of the water” cause outside perspectives to question whether Black students have grit and conclude that those who are “gritty enough” are an anomaly of endurance. Without recognizing the centuries of racism, boundaries and policies lack people have had to battle against for years, this narrative of grit is unmeasurable and anti-lack.

“Grit is in our DNA,” she writes, “but grit alone will not overthrow oppressive systems of power. We need teachers, school leaders and policymakers who have grit for justice. We need educators who understand the legacy of African-Americans’ grit—that we have survived because of it, and the surviving is not enough. Black people and brown people deserve the right to use their grit to thrive, not just survive.”

At NSO, Love stated the following: “ordinary people [shouldn’t be expected] to do extraordinary things.” Just because people aren’t in the shoes of “Grit Paragons,” whether that be in wealth or saving the world, doesn’t mean they don’t have grit. Duckworth agreed at NSO that grit shouldn’t be used to measure success, but rather it should be used as a tool to help students see their potential. Thus, success given life’s obstacles shouldn’t be measured when not everyone does not have access to an environment to thrive.

Despite the weight we might feel from this year, we all have grit; it’s how we got into college and faced adversity that comes with barriers throughout life. For the Class of 2024 and transfers, Stanford is another opportunity to grow our grit. It’s a new playing field to meet people that will support us and a way to utilize resources and put even more purpose into our work. Not only will we start to find our passion and satisfy our interests, but we will become part of the history of the social, ideological and political revolution that will continue after 2020. Now, we will find ways to help others, build support among our peers, ceaselessly fight against the systemic issues in the country, hold educational institutions accountable, remove barriers and strive to change the narrative of grit in our society.

Contact Kyla Figueroa at kylafig5 ‘at’ stanford.edu.