The U.S. military has the potential to effectively combat the climate crisis, Boston University professor of political science Neta C. Crawford said in an event sponsored by the Center for International Security and Cooperation on Wednesday.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) perceives “the problem of climate change as a short-term issue,” Crawford said, and is “unwilling to look at the causal role of their military emissions.” She contended that the department’s limited understanding of climate change, often confined to a military perspective rather than a broader global one, has caused oversights in its perception of the climate crisis.

The military is heavily involved in the creation of greenhouse gas emissions, Crawford said. According to her 2019 report, DOD activities have made up 77-80% of the U.S. government’s total energy consumption since 2001.

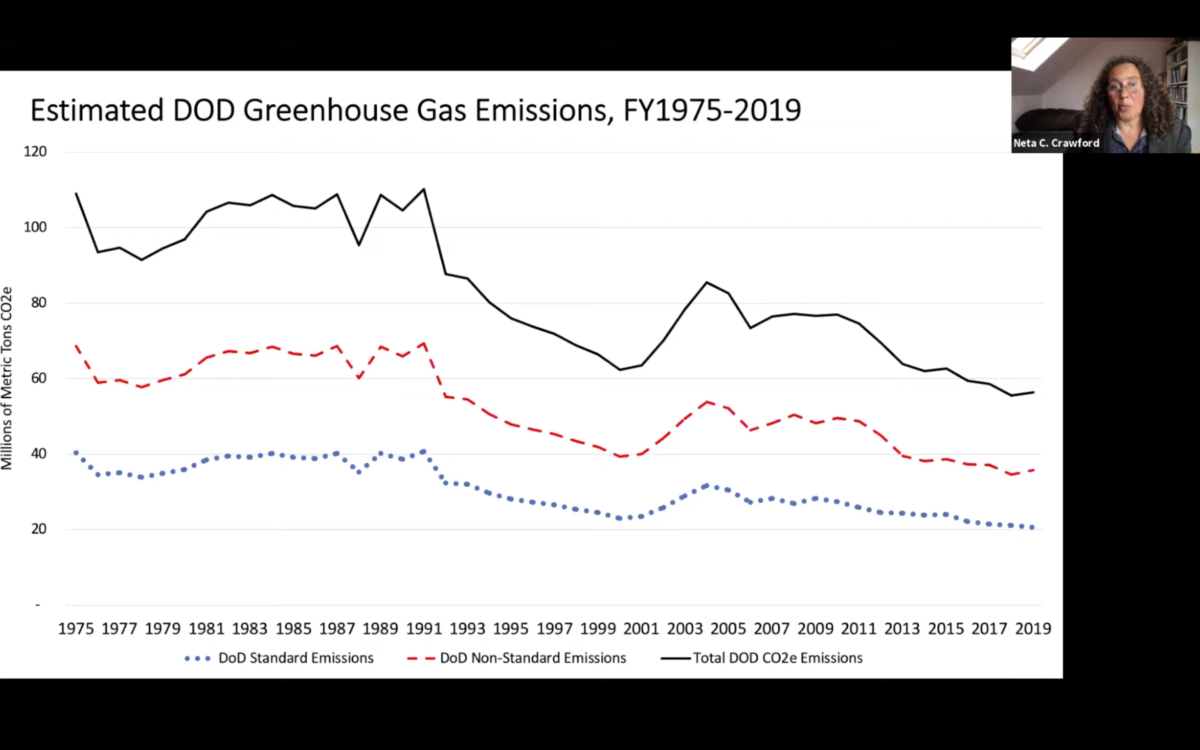

Furthermore, Crawford said that the U.S. military emits carbon dioxide amounts greater than some nations, including Morocco and Peru, citing a 2019 Forbes report on military emissions. She highlighted the correlation between emissions and military activity from 1975-2019; emissions decreased at the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s and increased following post-September 11 attacks operations in 2001, according to Crawford.

The Pentagon has taken a conflicted stance on the climate crisis, Crawford said. Although aware of the consequences of rising sea levels and the resulting long-term infrastructure deterioration, it turned a blind eye to the root of the problem: military activity.

“They’re well aware of the consequences,” Crawford said. “But they decided, even though they were aware of this, to do nothing about military emissions.”

The Pentagon instead has adopted a limited approach to the climate crisis — adaptation, not mitigation — according to Crawford. Crawford characterized preventing climate-induced damages to vulnerable bases as the military’s primary focus, adding that not addressing the root causes of the crisis is a “potential missed opportunity,” especially as it relates to the military’s ignorance of oil’s role in climate-induced conflict, according to Crawford. She predicted that the continued attacks on adversaries’ oil supplies could increase greenhouse gas emissions, climate insecurity and eventually geopolitical instability .

However, Crawford said that not all hope is lost for the States; she offered strategies to mitigate consequences of military-related climate impacts and to address the causes of the crisis. She recommended increasing governmental capacity to deal with climate change and its resulting insecurities, which she said would reduce the risk of international and domestic conflicts.

Crawford also encouraged significant reform of the Pentagon’s recent approach regarding the climate. She suggested re-evaluating the present significance, if any, of military forces and installations originating from the second world war and the Cold War that are still used today; unnecessary operations should be realigned and closed, Crawford said, thus preventing wasted energy.

She added that the military has the potential to spearhead efforts in alleviating the climate crisis.

“The military can lead and can show that this is not a red issue or a blue issue — it’s a national security issue, and they can lead in terms of innovation,” Crawford said. “The military is showing what is possible in terms of innovation in harsh environments.”

Contact Yewon Chang at ychang23 ‘at’ lawrenceville.org