Many musicians view the cello as the instrument that most closely emulates the human voice. Its range extends through the fullness of ours, from the Mongolian throat singer’s low C to the Italian castrata’s high E. Vibrato. A slight wavering in pitch caused by a trembling of the hand on the fingerboard also mirrors the dexterity and plasticity of the voice. When bow meets string, a cello can whimper, can weep, can entice, can beckon, can cry.

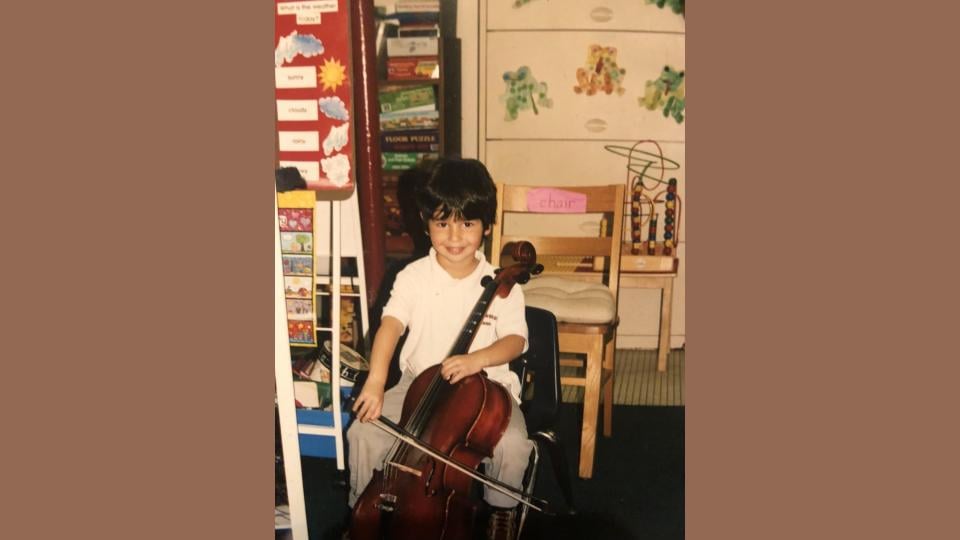

Like many precocious and hyper-energized kids, I was strapped behind a classical instrument for most of the first portion of my life. I did this along with my three older brothers, with each of us taking up a string instrument (think “Royal Tenenbaums” with a bit more emotional attention). Our teachers were a pair of beautiful and mouse-like women, with names that sounded like Mesopotamian spices, who taught cello and violin/viola. I studied cello from ages four to 15, and then again briefly at 18 — which is to say, for about half of my life so far.

Our instructors’ house was a small and beautiful stone home on the lip of North Philadelphia. Each week, I’d watch out the window of my parent’s car as the signs on the stores outside switched from English to Korean to English again — our houses were separated by Philadelphia’s Korean neighborhood — and arrive anywhere between 11 to four minutes early. I’d march up the stairs outside her house carrying my cello — this second body, which grew in size over the years as I did — until we both eventually stopped.

In the intermittent minutes, I’d wait in the front patio of their house, sink into whatever tchotchke they’d set out in the room. That too grew as I did — block puzzles, colonial cup-in-ball games, Reader’s Digest crosswords and a gradual swallowing into my phone. I’d sit and wait for my teacher until she’d peer out from the upper staircase and invite me to uncrack my cello from its case.

My teacher was strong, the first person who loved me that didn’t have to. She had callused hands with translucent hairs that grazed the tops of her knuckles. She called me Daniel, which no one calls me, and I let her. She told me I was seriously funny, which didn’t make sense to me when I was nine (how could something be serious and funny?), but now means more to me than most things people call serious or funny. She didn’t have any kids (once I got old enough, we’d joke about recurring men in her life), but she always held my cello as if it were a child.

One day, I learned that she’d only started teaching because, as a young cellist, she was robbed at gunpoint while walking on her sidewalk. The same sidewalk I scurried up once a week, the same sidewalk I sat on waiting for my parents to pick me up, the same sidewalk I occasionally (and looking back, regretfully) spat on. She lost her bag, some confidence and, most importantly, the unique teaching exercises she’d started writing down. Afterwards, she decided to start publishing her exercises and opened up her teaching studio.

At my next lesson the following Tuesday, she did not tell me she loved me or that she believed in me, and I did not tell her how lucky I was that she was alive. She simply showed me how to play, her fingers trembling from the vibrato, the cello making a sound like a whimper, a weeping, a beckon, a cry.