In the fall of 1997, the face of a smiling, striped-shirted Stanford student named Jesse Oxfeld ’98 was plastered across national media outlets. The headline? “Stanford Daily reporter spiked after writing a column about Chelsea Clinton.”

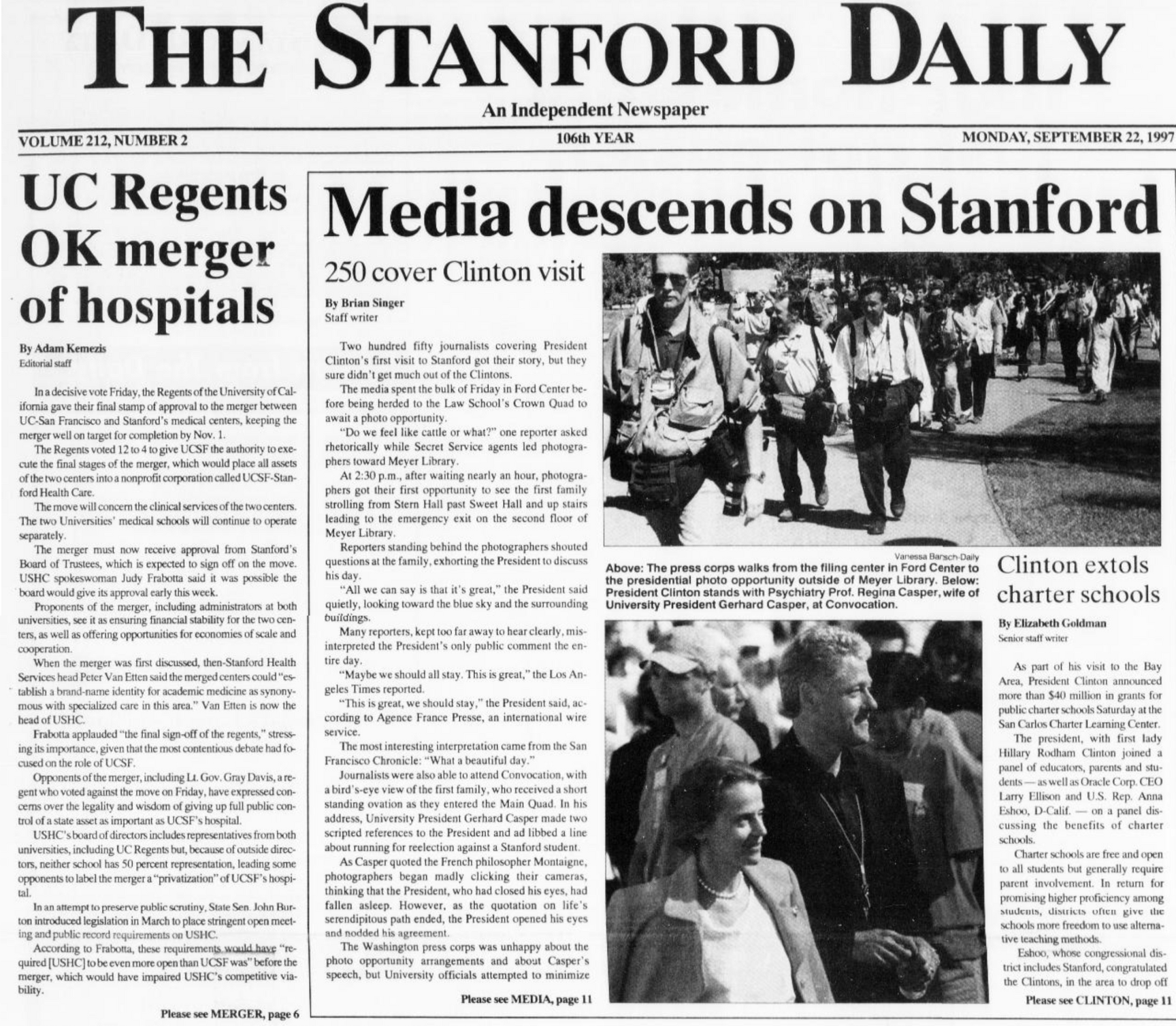

On Monday of orientation weekend in 1997, The Daily’s front page story went to First Daughter Chelsea Clinton’s arrival at Stanford, accompanied by a sizable group of aides, attending press corps — and, of course, former president Bill Clinton.

In response to the Clintons’ presence on campus, long-time paid Daily columnist Oxfeld wrote a column that was slated for publication on Sept. 26, 1997. The spiked column criticized Clinton ’01, the First Family and the University and said, “why are we all expected to bend over backward to give Chelsea and her family a ‘normal’ Stanford experience while the First Family is under no similar obligation?”

In Oxfeld’s spiked column, he quoted The Daily alumnus, Philip Taubman ’70 of The New York Times, who wrote in an opinion piece that “if the long-term goal is to discourage a preoccupation with Chelsea Clinton, the White House should have considered a less flamboyant way of getting her to school.”

Carolyn Sleeth ’98 — The Daily’s Editor in Chief at the time — provided Oxfeld with an ultimatum: “write something else or just publish nothing tomorrow,’” Oxfeld told The Daily. He said he refused to write an entirely new piece at 10:30 p.m. on Thursday, the night before print. According to Oxfeld, Sleeth responded, “We’re not going to publish anything by you for the rest of the volume.”

By drafting that column, Oxfeld violated an editor’s rigid policy: do not write about Chelsea Clinton in The Stanford Daily unless she does something newsworthy. As Sleeth wrote of the reporter’s dismissal in an open forum editorial, Oxfeld’s termination was not merely a result of covering Chelsea, but was the “culmination of a series of work-related issues that constituted cause for dismissal.”

Oxfeld told The Daily over the phone that the incident and resulting media attention didn’t change his life. Instead, Oxfeld said that the story was a “silly little gossipy thing … that prompted no larger national conversation.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever regretted trying to publish that column,” Oxfeld said. “I argued then and argue now that what I wrote and submitted was legitimate questions about the newsworthy events concerning [Chelsea’s] parents.”

National media outlets used Oxfeld’s dismissal to contextualize broader discussions surrounding their own coverage of the junior Clinton’s schooling, prompting scrutiny about how the famous daughter should be covered. Clinton is a public figure, and as the Washington Post wrote at the time, “if a columnist cannot write about the effects of a public figure’s presence on a campus known for its openness, not only he or she will be silenced.”

Now, over 25 years later, journalists still hold similar conversations about how to decide what is deemed newsworthy. There is no shortage of public figures on Stanford’s campus, including Olympic athletes, children of billionaires and, currently, disgraced cryptocurrency company owner Sam Bankman-Fried. Although there is currently no coverage rule as rigid as Sleeth’s at The Daily, the Clinton column controversy prompts a modern conversation about who gets covered and why.

Two sides of an untold story

The Chelsea Clinton column controversy, contrary to much of what the media was publishing at the time, wasn’t instigated because of a First Amendment or censorship issue. Instead, it was rooted in interpersonal challenges, according to Sleeth.

Sleeth told The Daily that most national media coverage at the time, including a gossip column piece written by a Daily alum, largely centered on Oxfeld.

“He told his side of the story, and I didn’t tell mine,” Sleeth said.

Rather than an isolated instance where The Daily fired a staffer, Sleeth said the controversy really unfolded in two parts within a week and a half of each other. The controversy began when Sleeth taped a letter to the door. The single piece of paper came to represent much more than a simple notice to The Daily staff.

Opening with the line, “To Daily staff …,” Sleeth’s policy was neatly partitioned into two points: first, cover Clinton like a normal student, and second, paid staffers are prohibited from covering Clinton’s campus activities for other news agencies. The latter policy, Sleeth said, was drafted with the intention of protecting Clinton’s privacy and preventing news outlets from taking advantage of Daily reporters.

The first wave of national media attention came after a San Francisco Chronicle reporter discovered the paper at The Daily house, subsequently publishing an article which described Sleeth’s letter as “taking the privacy policy a firm step further.”

According to Sleeth, the only place someone would have seen the paper would be the door of The Daily’s old building. Sleeth said she didn’t consult with The Daily’s Board when she posted the letter, because she didn’t think it would be that big of a deal.

“With the advice of managing editors, I typed out this policy in Word and printed it out. I didn’t think it was a big deal before it was picked up in The Chronicle,” Sleeth said.

The resulting media attention of the first story covering the ‘don’t cover Chelsea policy’ was largely positive, Sleeth said, and most outlets commended The Daily’s efforts to protect a fellow student. According to Sleeth, it wasn’t until Oxfeld’s dismissal for the Chelsea Clinton column broke into national news that The Daily’s reputation as a paper or the motives of its staffers were called into question.

Column controversy

During what both parties called a “hotly contested election,” both Oxfeld and Sleeth ran for the position of Editor in Chief in fall of 1997. Sleeth won. Per tradition, Oxfeld, a senior staffer at the time, was given a weekly opinions column — where the spiked Chelsea Clinton column was originally meant to be published. Instead, Sleeth said, an advertisement filled the space of the spiked column that Friday.

Sleeth recalled that the spiked column had three sections, focusing on critiquing the Clintons in the first, followed by Oxfeld’s critique of “a stop sign that was annoying him,” and a third section also filled with non-Clinton-related commentary.

“Of course there was animosity. For him to write that column challenged the policy — it was a challenge,” Sleeth said.

A week after being dismissed, Oxfeld said national media outlets pounded on his dorm room door. “Phone ringing off the hook. Voicemail box getting full. People Magazine knocking on my door,” Oxfeld said. “I had family members in Florida call to say that they’d read about me in The Miami Herald.”

However, Sleeth said her life became “overwhelming” after the second wave of national media attention following news coverage of Oxfeld’s dismissal.

“After the second story came out when it was framed as an ‘I censored Jesse’ issue, I got hundreds of emails — particularly hate mail — even from Stanford students,” Sleeth said, adding that there was no filter to sort emails into spam at the time.

The negative feedback, Sleeth said, could be partially attributed to gossip columns that rushed to pick up the story. For instance, Sleeth recalled the Drudge Report printing a blurb titled, “Student Reporter Fired In Chelsea Flap At Stanford Newspaper,” in their newsletter. Many news outlets framed the spiked column and Oxfeld’s subsequent dismissal as an issue of censorship — but according to Sleeth, censorship comes from a government, and The Daily is an independent, private business.

In contrast to “largely negative” portrayals of her decision in the media, Sleeth said she didn’t receive backlash for her policy within The Daily after holding a staff meeting that Friday. Gerhard Casper, the University’s president at the time, personally reached out to Sleeth to extend his support.

Reflecting years later, Sleeth recalls feeling afraid, a feeling that stemmed both from the intense media scrutiny of her decision and relative confusion when it came to navigating the media coverage of her actions.

“I was just a student. I was so young, and I wondered, how do I manage this? I thought a piece of paper on the door was enough to make my policy clear. Knowing what I know now, that the best way to get a point across is only a few words, I would have said: this is what I believe; this is what I’m doing; and this is why. I wish I could have been clearer, simpler and louder about those three points,” Sleeth said.

Perhaps if it had been 6 p.m., there could have been a discussion that resulted in a different conclusion, Sleeth said. Instead, it was 10:30 p.m. with an 11 p.m. print deadline. In time, Sleeth was grateful for the experience. Both Oxfeld and Sleeth noted that they are currently “good friends,” having met up at a mutual friend’s wedding and at several alumni reunions.

Ultimately, Sleeth stands by her policy: protecting Chelsea and preventing The Daily from becoming a tool for other media organizations hungry for a story about the famous First Daughter.

Newsworthiness in the modern day

Determining newsworthiness has long been a crucial editorial function of news organizations. In 1997, The Washington Post defined newsworthiness as “the short answer to, ‘What determines how a story is played?’” Even as The Stanford Daily celebrates its 50th year as an independent newspaper, the concept of newsworthiness and committing to that journalistic practice in an increasingly digital climate remains an ongoing topic of interest.

Oxfeld said he “fundamentally works in public relations now,” which ushered in a new understanding of journalism for him. He quoted George Orwell, saying, “journalism is publishing what people don’t want you to know. Everything else is public relations.”

According to Oxfeld, in the context of Stanford, what would typically be thought of as news has remained constant: the job of a newspaper is to report the news and uncover what’s happening. Newsworthiness is something you “argue about in academic journalism classes,” Oxfeld added.

Ted Glasser, a professor emeritus of communication who served as a Stanford Daily Board member, taught Oxfeld in 1997 and remembers him as a “bright, very self-promotional” writer. Contrary to several news organizations at the time, who used Oxfeld’s dismissal as a chance to question Stanford’s commitment to free speech, Glasser recalls the Clinton column controversy as anything but.

“An editor firing a columnist (or any staffer) is not — and has never been — a First Amendment issue,” Glasser wrote in an email to The Daily. “The column controversy involved insubordination, defiance and spite; if it illustrates anything, it’s that personal relationships can undermine professional relationships.”

Glasser added that The Daily “took the high road” by choosing not to cover Clinton. “News organizations from all over wanted Chelsea stories of any kind: who’s her roommate, what courses is she taking, what did she have for breakfast?” Glasser wrote. “There was good reason to believe that at least some of the questions coming from off campus would be salacious, intrusive and contrary to the kind of discourse Stanford wants to sustain.”

A news story requires readers to take action, Glasser said — which means legitimate news is “pragmatically meaningful.” A news story is assumed to be true, which is important because news inspires readers to take action, Glasser said, adding that most publications regard newsworthiness in terms of the public interest, as opposed to merely the public’s interest.

Ultimately, Glasser said, definitions of newsworthiness are driven by the “readers’ right to know.”

However, according to journalist Margaret Sullivan in “If Trump Runs Again, Do Not Cover Him the Same Way: A Journalist’s Manifesto,” the advent of the digital age rapidly called into question several key journalistic concepts, including whether traditional rules of coverage would apply to modern political figures like Donald Trump. In her piece for The Washington Post, Sullivan wrote that journalists who cover political figures must “keep a sharp focus on truth-seeking, not old-style performative neutrality.”

Photography: A human element

The shifting concept of newsworthiness doesn’t only function in reporting contexts; it also applies to a newspaper’s visuals.

“The journalist instinct is capture and then decide,” said Geri Migielicz, a Stanford Graduate School journalism professor and award-winning photographer. Migielicz worked at the San Jose Mercury News during the Marshall Plan era, a time when journalists followed a rigid and unwritten rule: no American newspaper should run images of deceased American soldiers. Ultimately, Migielicz believes the paper made the right choice, and said that “publications had a duty to report and document this brutal animosity toward US military presence.”

When evaluating newsworthiness, considerations surrounding whether a visual would advance the understanding of the story, as well as weighing safety risks and consequences, have remained unchanged in journalistic discussions.

Considering whether a controversial image should be published in today’s digital age can be more complex. Photojournalists have historically leaned on such things as disclaimers and editor’s notes; today, digital platforms provide readers with the option to filter, block or blur sensitive content, which was not an option back in the print-only era.

In the context of a college paper like The Daily, its photography of anti-Vietnam War protests drew concerns from University administration that the school might be held liable for any violence incited by the pieces published.

The Daily’s disentanglement from the University would make it impossible for the University to attempt to influence reporting through financial withholding or other means, and the University’s disentanglement from The Daily would release it of any potential liability for content published in the newspaper.

The American journalism industry is rapidly evolving, and the Chelsea Clinton column controversy of 1997 is not the only controversial incident in The Daily’s history. The debate has stood the test of time as a case study in the ever-present discussion of what is and isn’t “newsworthy.”