If you believe there is no action nobler than feeding your enemy, then the year 1922 is one of the noblest in American history. Under the leadership of Herbert Hoover, the American Relief Administration (ARA) fed over 10 million Russians daily during the severe famine that hit modern day Russia and Ukraine.

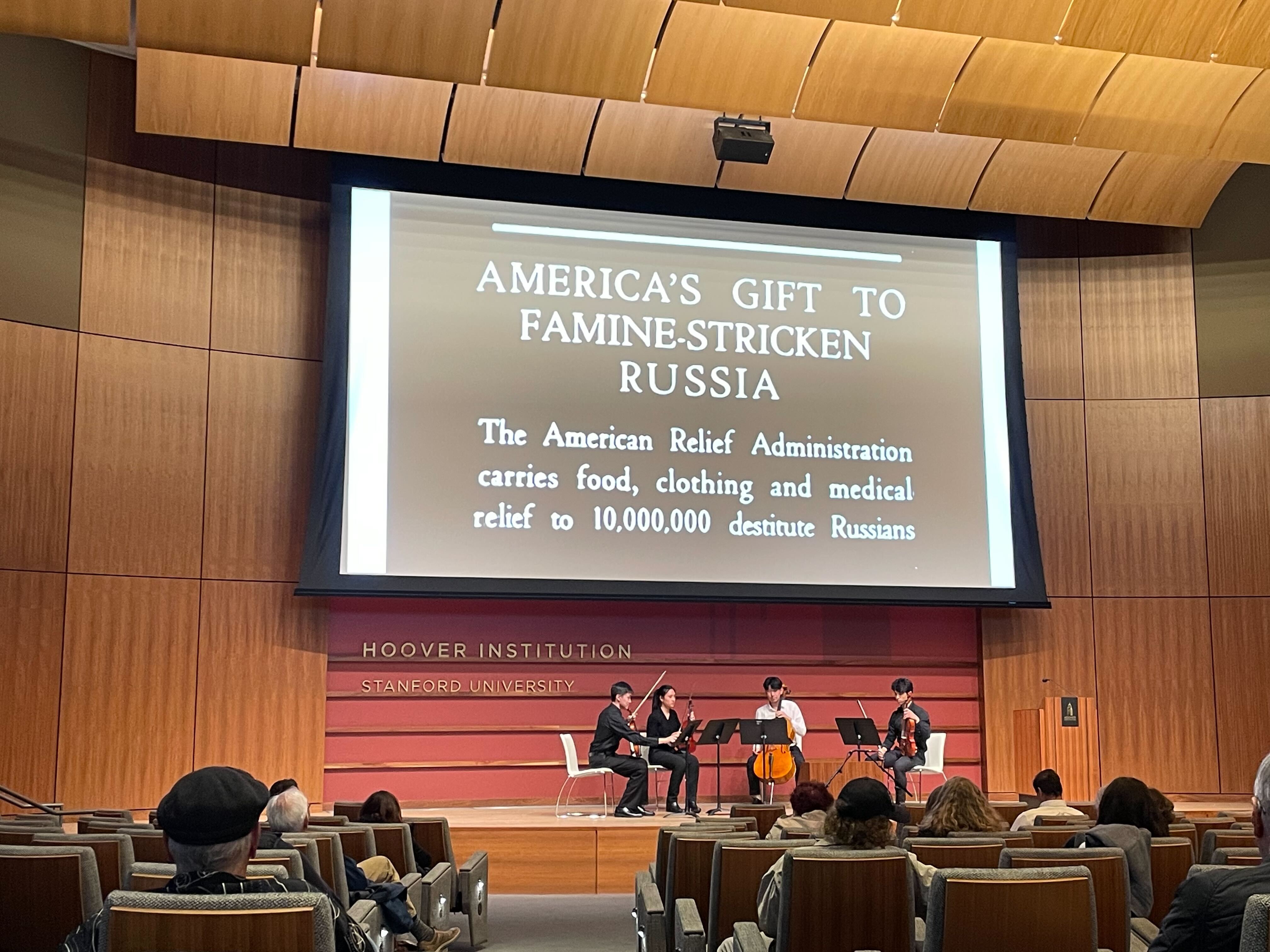

On Tuesday evening, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives’ premiere screening of the 1922 film “America’s Gift to Famine-Stricken Russia” showcased this selfless act. The motion pictures that made up the film, capturing ARA workers’ relief efforts, were distributed to 1,800 movie theaters across the U.S. in the first half of 1922, according to panelist and history lecturer Bertrand Patenaude MA ’79 PhD ’87. The film’s reach is a testament to the power of art in documenting important historical episodes as well as shaping public perspectives.

The screening of the silent film was accompanied by a string quartet (Roger Xia ’24, Audry Lin ’25, Bradley Moon ’25 and Jonathan Pak ’24) performing the musical arrangement of Pak and Jenny Xiong ’24. The selection included Russian classics such as Tchaikovsky’s String Quartet No.1 in D Major, which drew inspiration from Russian folk music. As the film began, musicians opened with Dvorak’s String Quartet No. 12. Nicknamed the “American Quartet,” the piece framed the film in the United States’ point of view.

Under the leadership of President Herbert Hoover (class of 1895), the ARA came to aid children and adults in famine-affected areas with corn ration and medicine to treat the typhus epidemic. The effort was funded by $20 million approved under the Russian Famine Relief Act of 1921.

“America’s Gift” is composed of snapshots capturing different moments of the ARA project, connected by black-outs and text. At times, the camera captures dozens of ARA workers lining up and unloading food and medicine off of a ship, and other moments show Soviet Russians standing in line for their daily ration of American corn. Most often, it zooms in on the faces of children and elderly as they consume “kasha,” or porridge, and smile at the camera.

One of the most memorable moments was a zoomed-in shot of a young boy feeding himself a spoonful of food. The bit was touching with its realism and earnest simplicity. After chewing, the angelic-looking boy wipes the corners of his lip with his sleeve, stares directly into the camera and grins.

I found myself captivated by his strong emotional pull — until I saw the text on the next black-out, which read, “Before the ARA came this child had never smiled.”

As a modern audience, I was at once transformed from sympathizing with the film’s cause to being acutely aware of its propagandist value. To a U.S. audience from the 1920s, however, I can imagine its power in convincing Americans to support a tax-funded project aiding citizens of a communist country.

The film impresses by portraying the impact of American aid. Hundreds of Russians line up on the streets of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) to receive food, wearing patched winter clothes. Refugees are shown on city outskirts, waiting to receive medicine for their typhus disease. The sheer view of over 10 million people being fed daily deserves awe.

“America’s Gift” also showcases people from different walks of life benefiting from the aid. One scene captures Muslim religious leaders of the Tatar people expressing gratitude to ARA workers by showing them their oldest copy of the Koran.

However, the film has no shortage of moments deemed “cringe-worthy” by Patenaude. One displays an entire village on their knees after receiving aid from the ARA. I found this moment especially troublesome. To me, the act is reminiscent of subservient imperial customs, but the film itself interpreted it as a passionate outburst of gratitude.

Many aspects of the screening are especially resonant today. In a post-Russian invasion world in which many Russian composers and artists are purportedly “canceled,” Pak worked with Patenaude to feature authentic Russian composition. More importantly, the film reminds us that even amid hostilities between Russia and the West, we citizens should treat each other with compassion.

Patenaude recounted how back when Hoover embarked on his campaign, skeptics worried that Hoover was “strengthening a dangerous enemy” in feeding the Russian people.

“You need to separate in your mind the 200 thousand communists in Russia from the 150 millions of Russian people,” Patenaude said, quoting Hoover. “This is a point that we should keep in mind today to resist the wide-spread Russophobia,” he added.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.