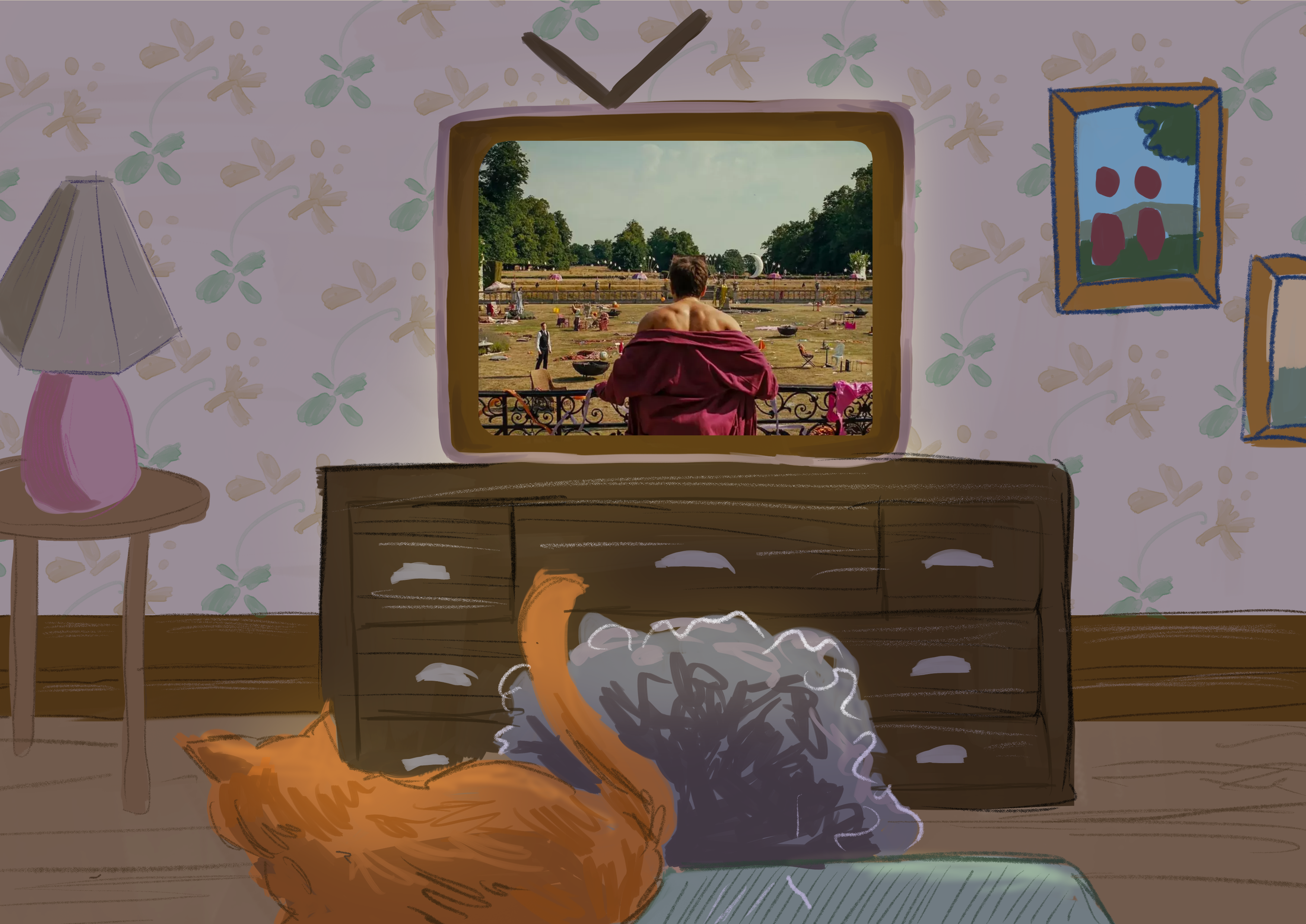

Emerald Fennell’s “Saltburn” (2023) is sure to leave any individual belonging to its target audience with a mischievous grin on their face and a skip in their step, while the upbeat tones of Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s cult hit “Murder on the Dancefloor” ring merrily in their ears.

Some more straight-laced, or dare I say sane, audience members might have the good sense to be disturbed by the film they had just seen. But the stylish, sex-positive, queer members of Gen-Z — the eldest of whom might yearn for a time just prior to the dominance of screens and social media apps — have largely embraced the sexy and outrageous mid-2000s aesthetic of the fictional Saltburn estate and its hedonistic residents.

We join our protagonist Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) at Oxford University, aptly poised in the class of 2007. Fennell chose the film’s time period because it is “not cool [and] super lame,” a sentiment the masses have already judged differently. Oliver meets Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), an absurdly popular and well-off student who takes pity on him, befriends him and invites him to his estate in the country for the summer. Chaos, beyond what you can possibly imagine in the dark dungeons of your mind, ensues.

Sex is everywhere in “Saltburn.” It is discussed, it is depicted and it is used frequently as a plot device. In a chuckle-worthy commentary on what the ultra-wealthy will and will not tolerate in their reality-detached social spheres, the residents of the Saltburn estate apparently throw all concerns about who has sex with whom out the window. Felix’s mother, Elspeth (Rosamund Pike), laments that her daughter, Venetia (Alison Oliver), needs to date someone, man or woman, and even cites her own temporary lesbian moment as evidence of this open-mindedness. Moments later, she nearly succumbs to the seduction tactics of Oliver — her son’s twenty-something friend — as if one can, of course, reach the point where hedonism shielded by wealth masquerades as progressive ideology on sex and sexuality.

Despite its portrayals of sexuality, “Saltburn” still vaguely queerbaits the viewer with Oliver and Felix’s friendship (and, by extension, with parasocial perceptions of Keoghan and Elordi’s relationship). Oliver’s implied obsession with Felix eventually gels in the context of his many manipulative tendencies, though not without leaving a desire for queerness as more than just an excuse to stir up pity and sexually charged bathtub scenes. The queerbaiting is absolutely frustrating and fairly unnecessary (unless you’re a producer marketing this film), but the rest of the sexual nonsense is fun — you just shouldn’t watch it with grandma.

Here’s another big problem: while the film happily plays into mocking stereotypes of the white upper class, “Saltburn” sidelines and completely removes agency from its singular main character of color. Oliver and the Catton’s cousin, Farleigh (Archie Madekwe), are exact foils of one another; while they have the same end goal of extracting as much as they can from the wealthy and airy Cattons, Oliver’s propensity for the violent and vulgar beneath his “boy next door” disguise propel him far beyond what Farleigh has evidently been able to accomplish in his entire lifetime.

If I am to suspend my disbelief that no one at Saltburn is even slightly concerned about Oliver’s shenanigans until it is too late, then why do I also have to pretend that Farleigh is incapable of the same insidious conniving? Farleigh’s treatment merits the greater argument that many of the film’s attempts at social commentary fall flat.

Yet, despite all that befalls the Cattons over the course of the film (unfortunately with zero points to Farleigh’s nefariousness), it is nearly impossible to pity them because they’re just so clueless. I have found this is often the case in contemporary black comedies centered around class (think “Triangle of Sadness” (2022) and “The White Lotus”(2021-)), so this is not a fresh take. Nonetheless, the absolution of concern for the Cattons’ welfare was what allowed me to enjoy the absurdity that coats the rest of the plot.

And absurdity truly is the highlight of “Saltburn.” It’s why this is a movie that is so fun for twenty-somethings in their most chaotic era of life, and also one that should probably be shielded from the eyes of unsuspecting citizens on social security. Could your grandparents handle it? Some, maybe yes. But I think the beauty, glory and insanity of “Saltburn” lies in how deliciously out-of-pocket it is, and you must willingly immerse yourself in this audacity in order to relish the experience. It is not saying anything remarkable about the world that you did not already know, unless you, like me, were missing some serious Barry Keoghan dance moves in your life. But the aesthetics and the shock factor are still working in its favor, all said and done, as long as you are willing to buy in. There is certainly a young, hip crowd of fans who are. We might be just this side of sick-in-the-head like dear old Oliver, but if you can handle it, who doesn’t love a little insanity?

I’ll leave you with my top 3 pearl-clutching moments (in secret code):

- Gravedigger

- The Bath

- Vampire