We’ve talked a lot about sexual violence on campus this year. We’ve discussed the high rate of assault and harassment and the low rate of reporting. But we haven’t sufficiently acknowledged the prevalence of retaliation against survivors, and how it prevents them from coming forward.

I am not writing about freedom of speech, or whether to discipline people for telling jokes. I am sharing what has happened to me over the past year. I am the student who was subjected to “intimidating and retaliatory conduct” based on a “false belief that [I] had reported Title IX concerns” whose experience was cited by the University in its recent decision regarding SAE. My story is a story of sexual harassment and retaliation against a Title IX witness. And unfortunately, it is a story shared by many people on this campus and beyond.

My story began when I attended SAE’s Roman Bath party last spring. The popular narrative surrounding that party is that SAE got kicked off campus for a few mildly sexist jokes, told at an optional event. Despite the ongoing tensions over that event, the real facts have never been published before.

“What do you tell a woman with two black eyes? Nothing, you’ve already told her twice.”

“What do you call the useless skin around a vagina? A woman.”

“What do a woman’s orgasm and her opinion have in common? No one cares about either.”

Those are among the jokes that were told that night, every single one of which targeted women. Those jokes, and the fact that SAE members cheered on the pledges they forced to tell them, are why I got up and walked out of the event. But — contrary to the false rumors spread by SAE — I did not report what had happened to Stanford, its Title IX coordinator or even my RA, not because I wasn’t upset, but because I was afraid of what would happen if I did.

To date, nearly every story about this event has claimed that SAE lost their house due to these jokes. I don’t take any position on whether it is appropriate to discipline a campus organization purely for offensive speech. But SAE did not lose their house because of the jokes alone. This unproductive dialogue overshadows the true reasons behind the University’s decision and the problematic culture of sexual harassment and assault on this campus.

This is what did happen, according to information I have gathered from other students who were present: Two students (including a member of SAE) went to the hospital that night. As is protocol, Stanford was informed of the hospitalizations. Word spread throughout the Greek community about the disturbing behavior of SAE and the emergency room visits. ASSU and the Inter-Sorority Council presidents sent a joint email to fraternities condemning this type of behavior and asking for change. That is how Stanford found out about Roman Bath — not from any one organization or individual, and not from me.

The Title IX office has the power to initiate investigations on behalf of the University without a complaining witness. They chose to do this for Roman Bath because this was not the first time they had heard of sexual misconduct or harassment at SAE. There had been many allegations of this type of behavior during the past several years, including a few in the previous year alone.

Over the summer, Stanford hired an independent investigator to look into Roman Bath. I was one of many people approached by, and who agreed to talk to, that investigator on a promise of confidentiality. We spoke for about half an hour, and I told her what I had witnessed at the short time I was at the party. Even after the harassment and retaliation I have faced, I do not regret the choice to leave the party or speak to the investigator.

I first learned that I was the target of harassment when I was on spring break in Cabo. I found out that SAE not only knew that I had spoken to the investigator, but also incorrectly believed I had reported them in the first place. They had been propagating this rumor and blaming me for the loss of their house since the beginning of Winter Quarter. They did so despite the fact that they had no knowledge of what I had actually said to the investigator, and that no individual had filed a report in the first place (a fact shared with them by the Title IX office when the decision was released).

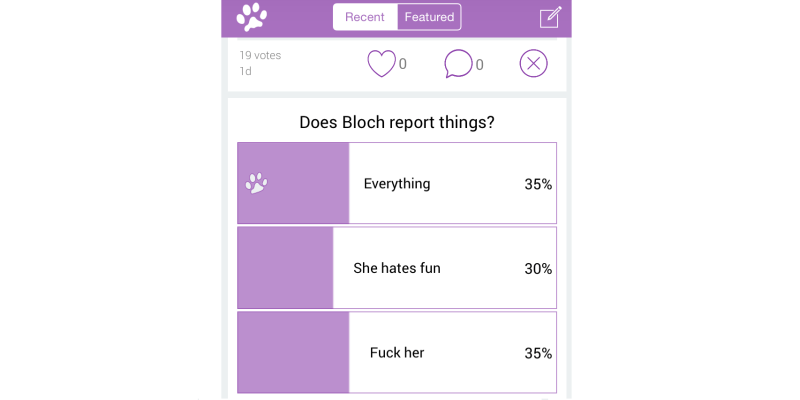

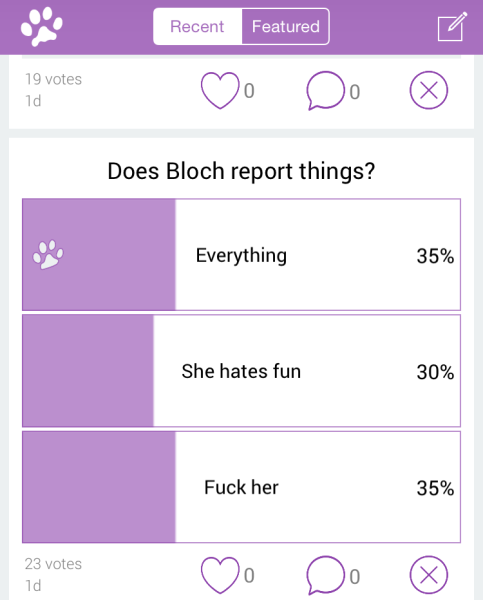

While in Cabo, the SAE members (whom I had been avoiding since the party) began to verbally harass me in person, singling me out for mockery and abuse. They made derogatory comments about me behind my back to my friends and peers. They tried to make my name synonymous with tattletale by targeting me on social media platforms, with posts like the one below.

I was the unwitting target of a concerted campaign of group harassment. And I felt a complete, terrifying loss of control, because I didn’t know how to make it stop. Reporting the harassment to the Title IX office didn’t feel like an option. It seemed that doing so would validate the false narrative that I had reported the Roman Bath event in the first place and only serve to increase the attacks. I called my parents, and we decided to contact the investigator to find out how SAE had gotten my name and whether other witnesses were at risk. As an inevitable consequence, the investigator learned of the harassment I was experiencing. She called Catherine Criswell Spear, the Title IX coordinator at Stanford, without my knowledge or consent. Criswell then emailed SAE’s leadership and legal advisor, who reached out to every member of the organization to warn them to stop their behavior. As I had feared, this only increased the harassment.

Feeling unsafe, I cut my vacation short and flew home to New York. I was there with my family for most of spring break, trying to process what was happening to me and to figure out what to do. I’ve never felt as unsafe as I did in Cabo, and as I feel on campus now. I am in constant fear of confrontation by members of SAE, who have continued to spread rumors about me and harass me. I still don’t know how SAE found out I talked to the investigator, or why they think that I’m the one who reported Roman Bath. But even if I had, I would not deserve to be harassed and retaliated against. No one does.

When I returned to campus, I met with Catherine Criswell Spear to discuss my options. I found out that because of how seriously the Title IX office takes retaliation against witnesses, they were going to move forward with an investigation with or without my cooperation or consent. In fact, my case was being rolled into a larger organizational investigation into SAE and whether they had broken their probation.

For the first time in this process, I was given a choice — albeit a small one. I could choose to participate in the investigation, or I could remain silent. I chose to participate.

This was not an easy choice. My only chance to protect myself was to participate in the same Title IX process that had made me a target in the first place. I knew that any decision I made would affect not just me, but the culture surrounding reporting on campus. I am a victim of harassment and retaliation, and this experience has been among the hardest I have ever had to deal with. I cannot imagine what it must be like for victims of violence and assault. Given the retaliation I faced for merely being thought to have reported harassment, I don’t know if I could face actually reporting a case of assault. And I am not willing to become a cautionary tale, an example of the reasons why people shouldn’t report.

Many women, including members of the Greek community, have already come to me to share their stories of sexual assault and their fear of reporting. Despite the efforts that are being made around this issue, no policy changes will be effective unless people feel safe coming forward and reporting what has happened to them. We are not in kindergarten anymore. This is not about someone tattling to her teacher about stolen crayons. This is about people’s lives, education and safety. There is nothing wrong with reporting something as serious as sexual assault or harassment. And no one should be retaliated against for standing up for themselves or for those around them.

Along with SARA and the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life, I will be leading a working group as a part of the Violence Intervention and Prevention pilot program to foster a culture that condemns retaliation, and supports those who come forward. This group will pursue educational and preventive campaigns against retaliation. We will work to implement systemic changes in how retaliation is handled, because a survivor should not have to go through the process that victimized them in the first place in order to seek justice.

These measures should not and will not include banning Greek life. Despite everything that has happened to me, I have experienced firsthand the positive influence Greek life can have. In fact, I would not be able to share this story without the strong support system that the Greek community has created for me.

There’s a widespread belief that Stanford wants to kick the Greek community off campus. I do not believe this is true, and I can say that based on assurances from multiple sources in the University administration. But this fear contributes to the culture of retaliation. When anyone reports a Greek member or organization, they are perceived to be threatening Greek life as a whole. This belief makes the community turn against the victim in an attempt to protect themselves. Instead, we must start supporting the victims and turning against the perpetrators in order to create the safe, supportive environment that I know we are capable of.

I am not the only reason that Stanford decided to sanction SAE. My case is one of several issues the University investigated regarding the fraternity. But regardless of its origins, the decision to further discipline SAE, including suspending their housing privileges indefinitely, is an opportunity — not an opportunity to debate whether or not to discipline people for telling jokes, but a chance to take a stand against harassment and retaliation.

The University claims in its press release that it “will not tolerate conduct that intimidates students for speaking out when they believe they or others have been wronged.” In that same press release, Stanford acknowledged that it had cautioned SAE at the conclusion of the prior investigation that “any further misconduct could result in additional sanctions, up to and including loss of charter recognition.” SAE was found guilty of further misconduct. I am not necessarily saying that they should have lost their charter; I know there are well-meaning individuals in SAE, and I have personally experienced and appreciate their efforts. But as Stanford acknowledges, these efforts were unsuccessful — and because of that, I have suffered.

Stanford’s decision to allow SAE to keep their charter, despite their knowledge of SAE’s failure to change and their ability to impose that sanction, makes me question how seriously they take retaliation. By not following through, is Stanford telling us that retaliation doesn’t matter enough? Are they telling me that my experience is not important enough? And are they telling future victims that they shouldn’t bother to come forward, because their voices will not be heard?

SAE decided to target me by making my name synonymous with reporting. The irony is that while I was not that person to begin with, their actions have forced me to become someone who is willing to embrace the title, and finally stand up and speak out against them. We need to start asking ourselves why people are being retaliated against for coming forward in the first place — and why we as a community have accepted the underlying atmosphere of sexual harassment, intimidation and misogyny for so long. And I hope that in sharing my story, I can do what Stanford has not. I hope that I can help create a culture where no one lives in fear of telling the truth.

Tess Bloch-Horowitz ‘17

Contact Tess Bloch-Horowitz at tbloch ‘at’ stanford.edu.