When it comes to hosting controversial speaker events, the Stanford College Republicans (SCR) might have a card up their sleeve, according to former SCR Vice President Phillip Eykamp ’20.

The Leonard Law is a controversial California state statute extends some First Amendment protections to students at private colleges in the state and has increasingly become the subject of free speech discussions on campus, ranging from Faculty Senate meetings to conversations between students. Eykamp told The Daily the law is a trump card for SCR, enabling it to host its events without fear of being blocked by the University.

However, Eykamp’s interpretation of the law has been challenged by University figures like law professor Michael McConnell and Provost Persis Drell, who say it has not had any bearing on campus speaker invitations.

California is the only state that has a law extending the First Amendment to private universities. Written by Republican State Senator Bill Leonard and signed into law in 1992, the Leonard Law prohibits private colleges from subjecting a student to disciplinary action for speech that would otherwise be protected by the First Amendment or the California Constitution’s free speech clause.

“The University knows it can’t ignore our objections because without a legitimate reason, there’s the Leonard Law and they could have a lawsuit on their hands,” Eykamp said. “Just the threat of a potential lawsuit if the University misbehaves is enough to move the conversation from ‘is the event allowed to happen?’ to ‘how is the event going to happen?’”

Drell wrote in an email to The Daily that it isn’t the Leonard Law that’s enabling these speakers to come to campus, but instead Stanford’s commitment to free speech.

“When organizations within our community genuinely want to hear an outside speaker, the university will support their efforts as long as university policies are followed in the planning of the event,” Drell wrote. “I am not aware that the Leonard Law, specifically, has influenced decisions about whether outside speakers with controversial ideas can be invited to campus.”

Law professor, Senior Hoover Institution Fellow and First Amendment expert Michael McConnell agreed with Drell that the Leonard Law has not had a role in campus speaker invitations.

“The Leonard Law is only about disciplining students for exercising their free speech, not inviting speakers to campus,” he told The Daily.

Still, the Leonard Law has come back into discussion among students and faculty through SCR’s ongoing controversial speaker events. Members of the Stanford community have raised concerns about both the intent of the SCR’s events and the enforcement of the Leonard Law.

A history of SCR’s campus speech disputes

In November 2017, SCR kicked off what would become an ongoing campus controversy about the limits of campus free speech with the invitation of Robert Spencer, who directs the blog Jihad Watch and co-founded the ad organization Stop Islamization of America, which is listed by the Southern Poverty Law Center as an anti-Muslim group.

In a Faculty Senate meeting held the month of the Spencer event, Drell defended the University’s decision to provide funding.

“We need to defend free speech,” Drell said. “If it costs, it will cost.”

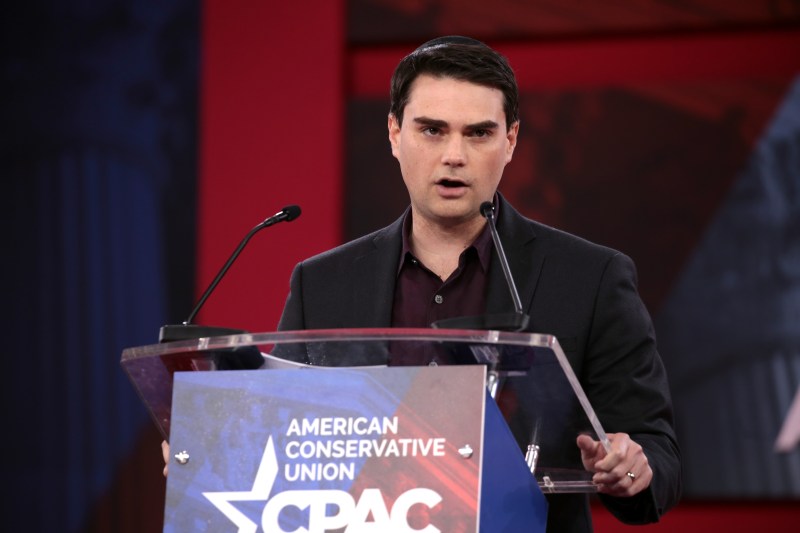

SCR followed with more events featuring speakers like Turning Point USA leaders Charlie Kirk and Candace Owens, conservative filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza, and most recently, Ben Shapiro, editor-in-chief of conservative publication The Daily Wire.

In a 2018 Faculty Senate panel on campus free speech and academic freedom, Stanford Law professor Jenny Martinez said that because Stanford is a private institution, the First Amendment does not necessarily determine actions Stanford can take in regards to speech.

She said Stanford has a commitment to free speech beyond the Constitution.

“Stanford protects free speech and First Amendment values as part of its commitment to academic freedom,” Martinez said.

However, later in the panel, Martinez added that the Leonard Law introduces some restrictions to how Stanford can handle free speech disputes on campus. Most notably, the law prevents Stanford for punishing students who engage in verbal discriminatory harassment on campus.

The Leonard Law first came into conflict with Stanford’s speech codes after a 1990 interpretation to Stanford’s Fundamental Standard. Titled the “Grey Interpretation” and introduced by then-Stanford law professor Thomas C. Grey, the interpretation aimed to protect students from discriminatory harassment on the basis of protected classes like race, sexual orientation and religion.

Nine Stanford students led by Robert J. Corry sued Stanford, contending that the new speech code violated their rights under the Leonard Law. Stanford responded by arguing the code only prevented fighting words and that as Stanford was a private university, the Leonard Law was an unlawful extension of the First Amendment. In 1995, the Superior Court of Santa Clara County ruled in Corry v. Stanford University that the speech code was a violation of the Leonard Law and struck the code down.

Then-Stanford President Gerhard Casper, in a statement to the Faculty Senate after the decision, expressed disappointment in the ruling.

“I thought the First Amendment freedom of speech and freedom of association is about the pursuit of ideas,” Casper said. “Stanford, a private university, had the idea that its academic goals would be better served if students never used gutter epithets against fellow students.”

Drell maintained that Stanford is committed to free speech, while recognizing the potential for speech to pose a threat to certain groups.

“Fostering both open expression and true inclusion can be challenging,” Drell wrote. “One of our most important educational goals to ensure students are prepared for democratic citizenship is to prepare students to defend their deeply held values and perspectives against dissenting opinions.”

New perspectives or ‘morally appealing’ content?

Eykamp said that SCR invites speakers with the goal of improving discourse.

“The idea is to bring some issue of relevance to the student population and a perspective that wouldn’t otherwise be given a lot of weight,” Eykamp said.

Stanford professors and students have expressed reservations about the value of SCR’s speaker events.

Education professor emeritus Eamonn Callan, who was also a member of the 2018 Faculty Senate panel, called for more active opposition by the University toward speech and speaker events containing “morally appalling” content.

“When the right to free speech is exercised by students, it doesn’t follow that administrators and faculty should simply sit on their hands and listen passively,” he said. “The best response to bad speech is more speech. And I worry sometimes that University leaders are too reticent when free speech crises arise to forcefully enunciate the liberal values we stand for.”

“It’s very important for University leadership to explain that just because the University does not interfere [with the event] should not be construed in any way as an endorsement of the views of the individual who is invited,” Callan added.

He also characterized the Leonard Law as an unlawful extension of the Constitution. He noted that he viewed speaker events as an extension of students’ First Amendment rights on campus, giving the University less latitude to restrict such events under the Leonard Law.

“The Leonard Law made it impossible for us to continue restricting the most egregious kind of hate speech,” he said. “We have a right as a private university to constrain speech, and I’m inclined to believe the Leonard Law violated that right.”

Comparative literature professor David Palumbo-Liu drew a distinction in an email to The Daily between speakers who “might appear controversial” and speakers who “are not here to share ideas and engage in conversation and discussion so much as to get attention for and recruit for organizations that have proven to be antagonistic to free speech.”

Palumbo-Liu wrote that SCR events like the one held with Kirk, the founder of Turning Point USA (TPUSA), had the potential to stifle free speech.

Citing Joerg Tiede of the American Association of University Professors, Palumbo-Liu wrote that TPUSA’s “Professor Watchlist” could prevent professors from freely speaking in their classes out of fear of being placed on the list.

Palumbo Liu concluded, “This is astounding and extremely disappointing. Speakers who come to campus to recruit for groups whose aim is to stifle free speech in such ways should be treated differently, I believe.”

Ruben Kruger ’21, who took part in protests outside of the SCR’s fall Ben Shapiro event, emphasized that while he does not agree with the positions held by Shapiro, said he supported the University allowing the event to happen, provided that he was able to protest.

“Stanford should always support free speech and intellectual diversity,” he said. “This campus is so progressive and people are so left wing in their views that there isn’t really a voice for anything that isn’t super liberal.”

Kruger further noted that federal funding could bind Stanford to local, state and federal regulations regarding free speech.

Ravi Veriah Jacques ’20, co-founder of liberal campus publication the Stanford Sphere, said that despite his opinions on specific speakers, he did not view it as the University administration’s role to regulate events.

“I don’t see it as on the ASSU or the administration to determine if speakers like Robert Spencer should come,” Jacques said. “I think it’s on the left to just not pay attention, as we did for Charlie Kirk and Candace Owens.”

Jacques also described the Leonard Law as a tool that “undermines freedom of speech itself.”

“Freedom of speech is less important than freedom of discussion,” he said. “The right just wants the right to polemicize demagogic opinions that get broadcast on Fox so that the left looks like it opposes free speech.”

SCR’s funding concerns

According to Eykamp, SCR has especially ran into trouble hosting events when it comes to procuring funding, as not many academic departments or student organizations have been willing to help fund the group. Stanford’s Office of Special Events & Protocol mandates that for events requiring security or extraordinary resources procure at least half of its funding from on-campus sources.

Zintis Inde, a sixth-year doctoral student in cancer biology and former director of academic freedom for the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU), said he respects the value of the Leonard Law.

“There’s a reason the Leonard Law passed,” Inde said. “It’s important to protect free speech and ensure that people have the rights to speak their opinions, even though Stanford is a private university.”

The ASSU has come into conflict in the past with the SCR over event funding decisions. In 2018, the ASSU voted to not fund the SCR’s Dinesh D’Souza event following concerns that some event funds had been earmarked for alcohol. Soon after, the SCR threatened legal action against the ASSU on First Amendment grounds. The conflict was ultimately resolved after the SCR filed a Constitutional Council case against the ASSU, and the ASSU voted to approve funding for the event.

Inde said he was not sure if the Leonard Law would apply to the ASSU’s funding decisions.

“Those questions are open to interpretation,” Inde said. “And there’s a fear of actually litigating those in a courtroom setting.”

Inde declined to comment on specific speaker event funding decisions but said positive intent is important when creating events.

“When you lose the good intent and good faith, when speakers are invited as a political move, that is when groups are not doing a service to the Stanford community or themselves,” he said.