Under Brassaï’s lens, Paris is shrouded with mystery, yet in the darkness of shadows, truths creep out. In the strictly realistic realm of photography, Brassaï expands into the magical space of mirrors. His photography is, in itself, a mirror of society, capturing its most promiscuous aspects; within the photos, mirrors are used to reveal people’s best kept secrets — our emotions. Born in 1899, Gyula Halasz adopted the pseudonym Brassaï in honor of his hometown of Brasso, Transylvania. His famous photography collection, “Paris de Nuit,” wanders through the streets of Paris at night, illuminated by foggy lamplight. Under his lens, the honest Paris unfolds — dirty, forlorn, hysterical, delusional — each character a work of art.

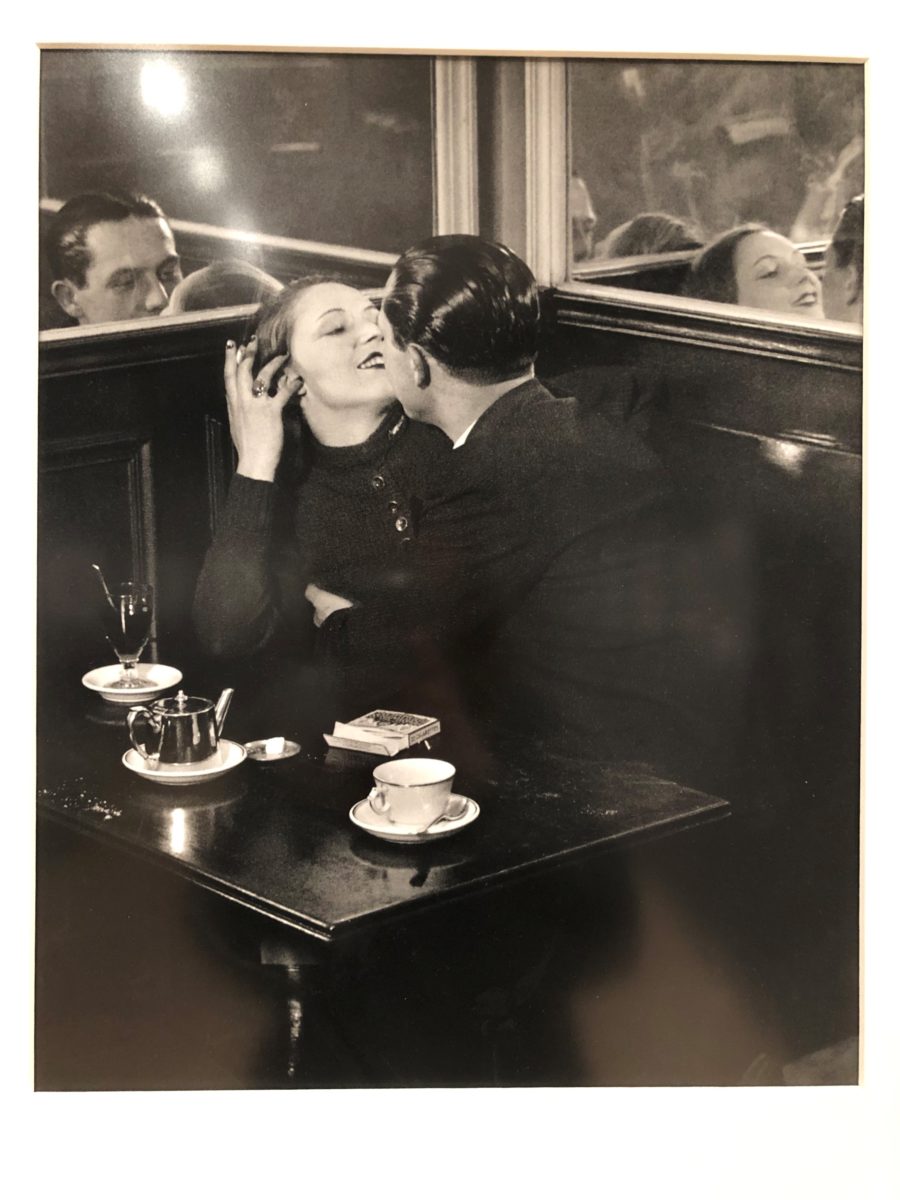

In Brassaï’s photographs, mirrors happen upon the perfect place at a perfect angle to expose a side of Parisians hidden from the camera. Boundaries between the real and imaginary are blurred in “Gala Soirée at Maxim’s,” where the mirror reaches deeper into the restaurant as a continuation of what could not fit within the camera frame. This venture into spatial depth is replaced by an exploration of emotional depth in “Couple in a Café.” A mirror animates the couple’s relationship with new life. As the woman leans back with a playful smile, her flamboyance is balanced by her partner’s intent gaze captured in the mirror behind her. Their brief interaction lives on in an infinite reflection between the mirrors, which is Brassaï’s effective way to let their intimacy resonate with viewers through time.

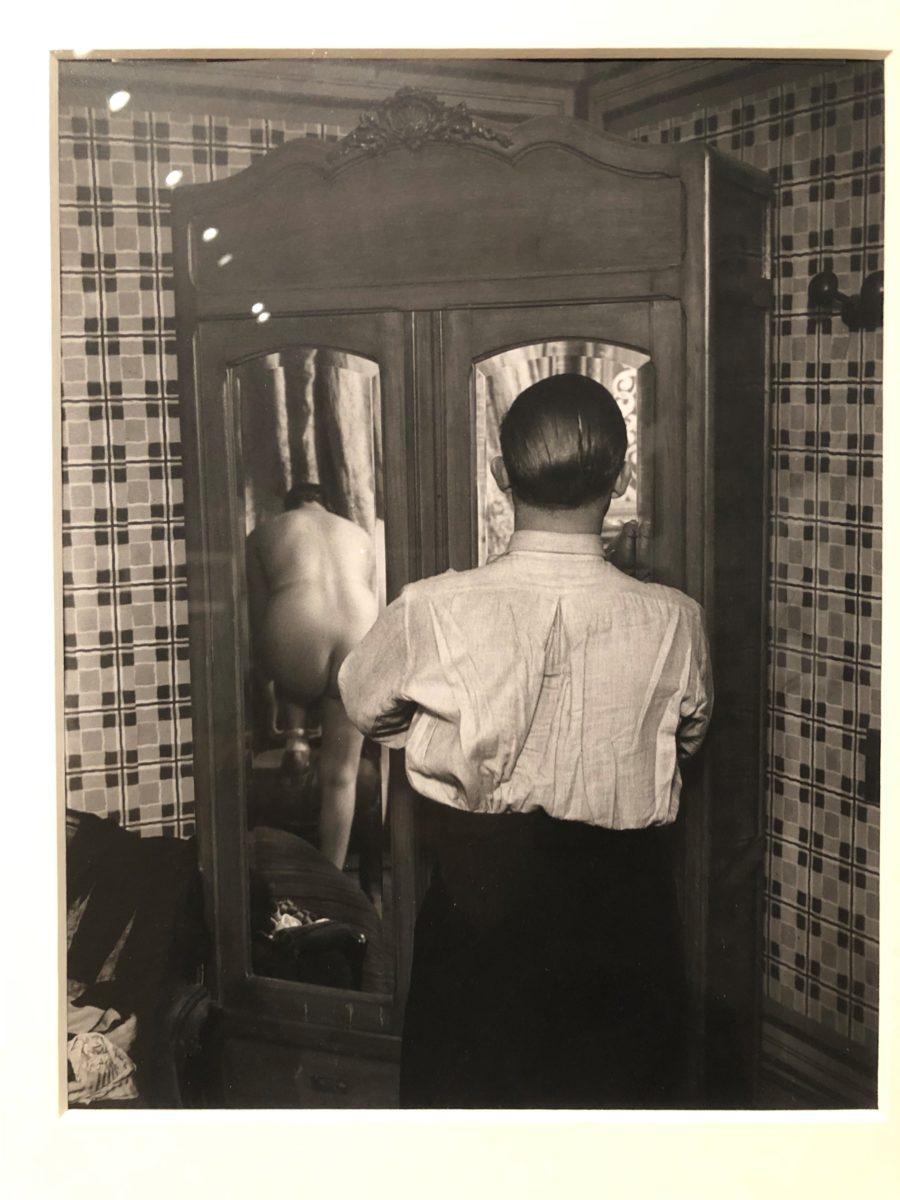

Couple in a Café Near the Place D’Italie, 1932 (courtesy Betty He) Chez Suzy, 1931-1932 (courtesy Betty He)

That intimacy is lost in “Chez Suzy” as the mirror reflects not a loving look but a voyeuristic gaze. Although the man has his back to the naked prostitute, his sight aligns with her image in the mirror. Their hidden faces leave the picture emotionally neutral, so that Brassaï does not judge either of them. In a way, he is also turning his head, only pointing his camera to depict varying relationships in the city without commentary.

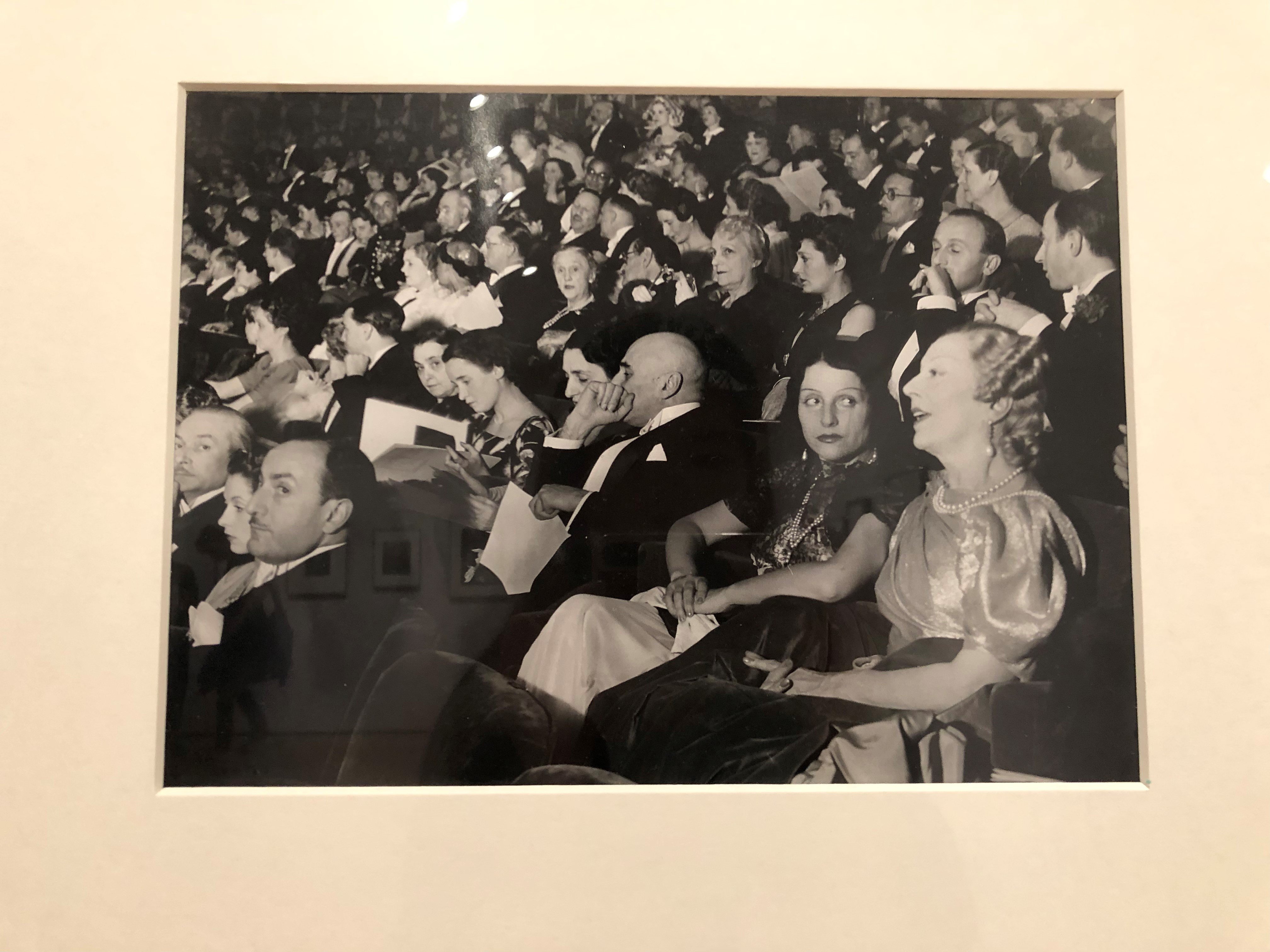

Within Paris, people are so deeply intertwined that they become mirrors of each other. The two couples in “Soirée at the Home of Princess Chavchavadze” could easily have been the same couple frozen in two different moments in time. Through capturing their presence in each other, Brassaï transcends photography’s static nature to fixate the couples in continuum. In “Cécile Sorele at a Screening of a Film by Sacha Guitry,” three women stand out from the crowd by staring at the camera in surprise. Of the two women in the background, one looks startled while the other merely looks. The woman in the foreground faces the camera yet her eyes dart toward something else that has absorbed her attention. By provoking these varying reactions, Brassaï elicits three different narratives from the women, who otherwise would have vanished into the crowd.

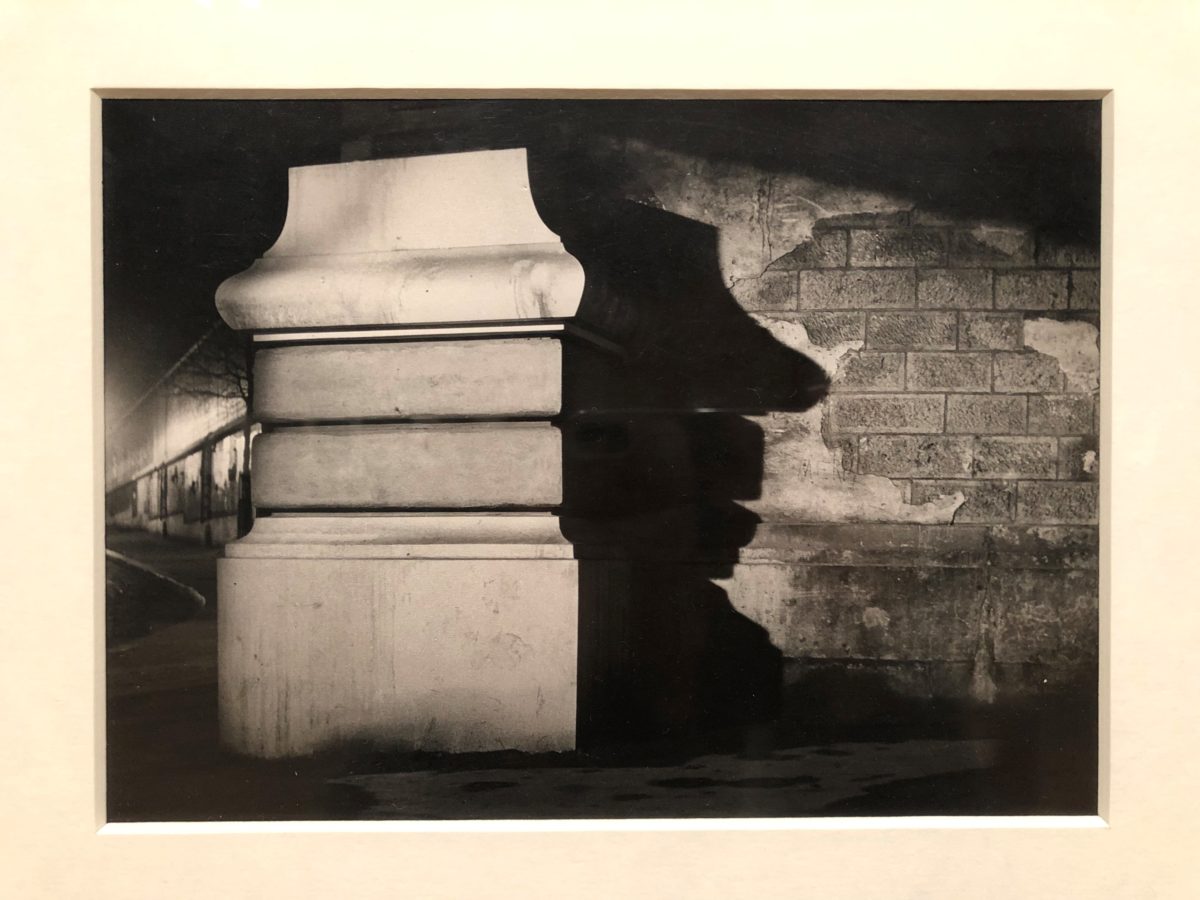

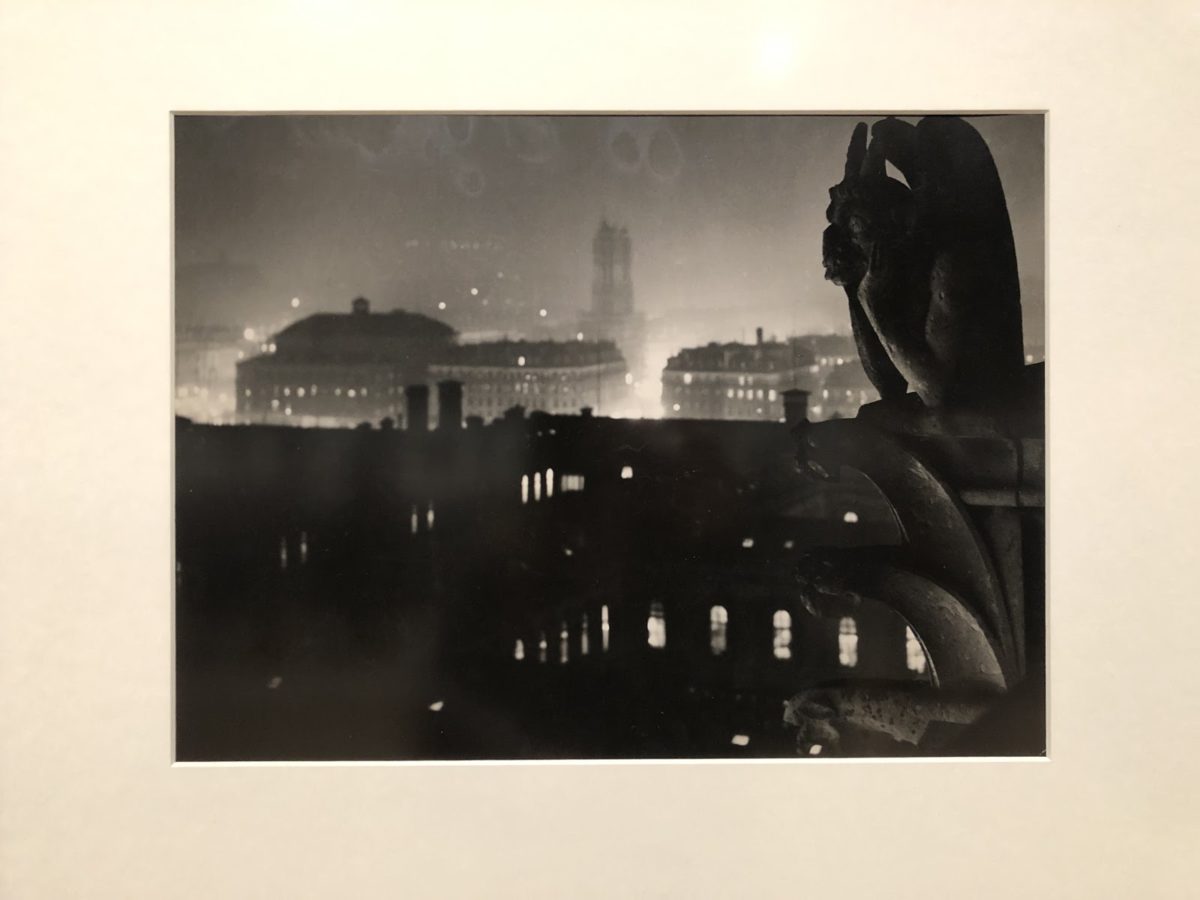

Buttress of the Elevated, 1935 (courtesy Betty He) View of Paris from Notre Dame, toward the Hotel-Dieu and the Tour Saint-Jacques, 1933 (courtesy Betty He)

A shadow cast on the wall in “Buttress of the Elevated” lurks suspiciously like a face in the dark, solemnly ignorant to the road curling behind leading to the city’s secrets. It assumes a dramatic deadpan similar to the hooded man in “Festival in Seville” such that both figures are deeply subsumed in what they turn away from. Meanwhile, an all-seeing gnome perches high above in “View of Paris From Notre Dame,” sunken in contemplation of a city impenetrable by sight. Brassaï poses the gnome as a double of himself, yet the city does not open up to the gnome as it does him, because of its distance from the people within.

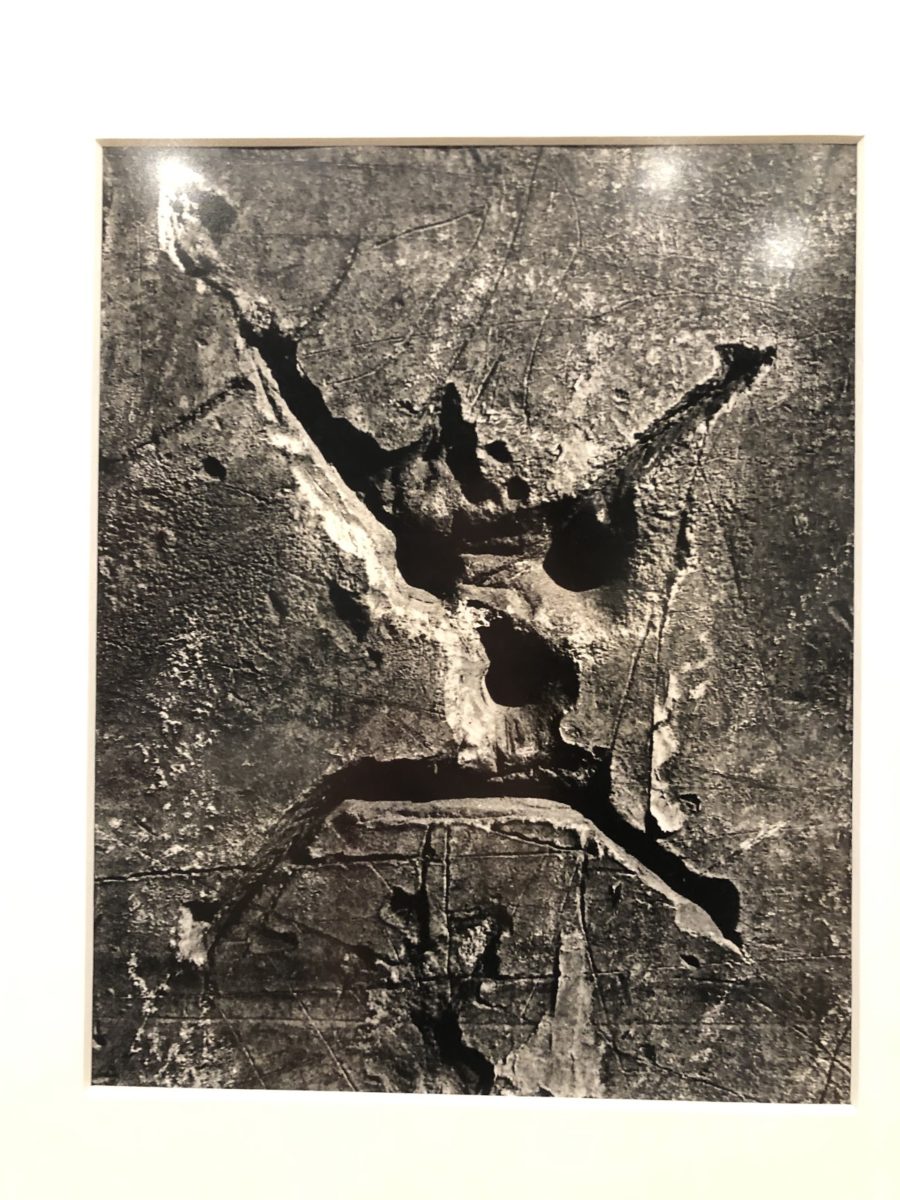

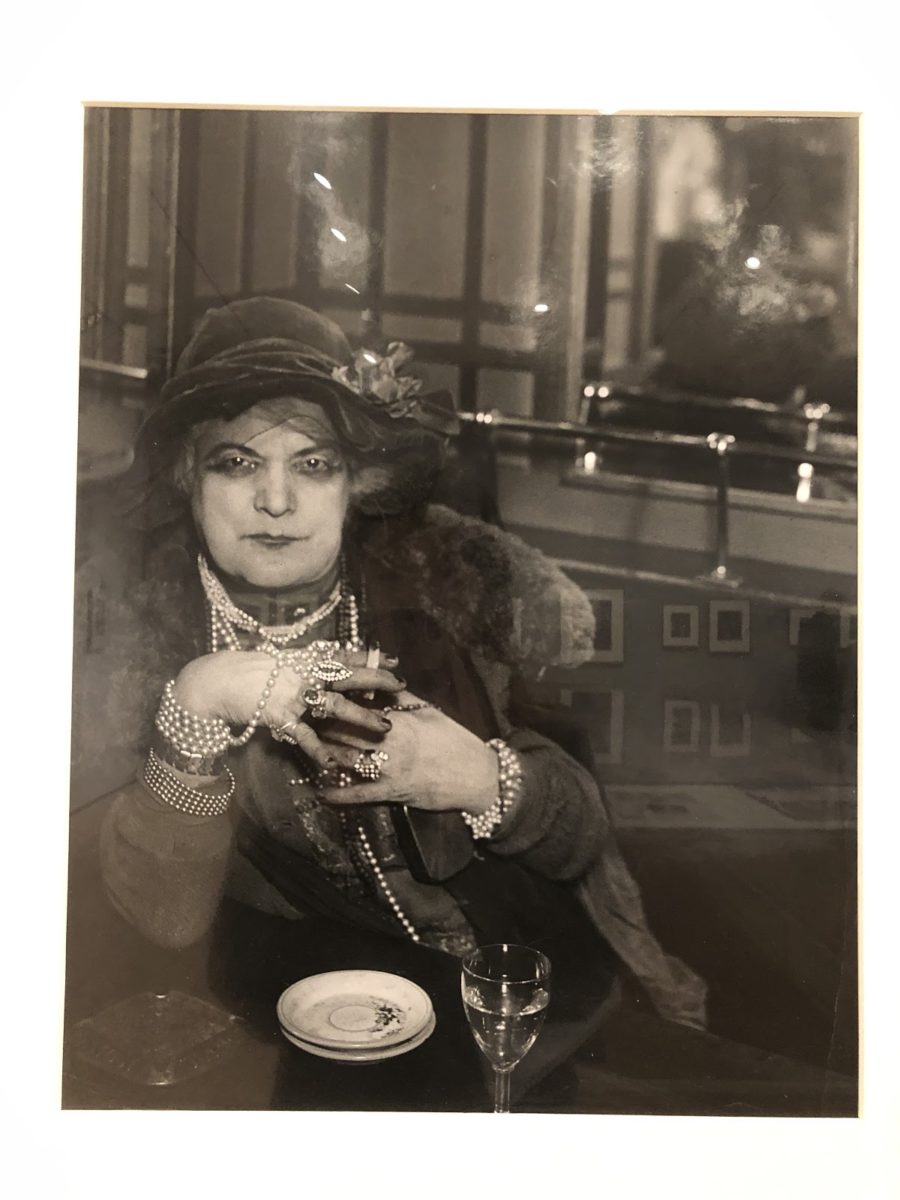

Untitled, from the series Graffiti, 1955 (courtesy Betty He) La Môme Bijou, Bar de la Lune, Montmartre, 1932 (courtesy Betty He)

Contact Betty He at hebetty ‘at’ stanford.edu.